By Najib Shah

Bengaluru, August 15 (newsin.asia): The recent announcement by The National Gallery of Australia that it is returning 14 works of art to the Indian government is welcome news. These include works connected to art dealer Subhash Kapoor, presently interned in Chennai awaiting trial on charges of running a smuggling racket; the US authorities have also sought his extradition to face similar charges there. This is the fourth time the NGA has returned to India illegally exported works purchased from Kapoor.

A good number of antiquities have been retrieved in recent times – in reply to a recent parliament question, it has been mentioned that the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) has received as many as 36 antiquities from foreign countries over the last five years. All the antiques recovered having been given voluntarily by the museums and related authorities of three countries.

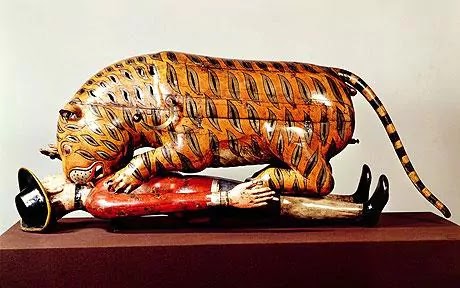

Which brings us to the larger question-have all the artefacts stolen from India been returned? The answer is an unequivocal no. The large-scale looting of antiquities in India has been fair game for a long time. Britain with its long colonial history is by far the worst offender. The celebrated British Museum makes ‘a visitor from a post-colonised country, very aware how his or her past has brutally been ripped away and appended to British history ‘. The Museum has a gallery on exhibits from India. This is apart from the other London museums which display relics of India including the reputed ‘Kohinoor’ and ‘Tipu’s tiger’, taken by East India Company officials after the siege of Seringapatam in 1799.

All colonial rulers-Netherlands, France, Italy have initiated the process of returning artifacts taken from their colonies. In January 2020, the Netherlands returned 1500 artefacts to Indonesia. The blue and gold Canon of Kandy, seized in 1765 by soldiers of the Dutch East Company and displayed in the Prince of Orange’s cabinet of rareties is in the process of being returned to Sri Lanka. The French senate voted unanimously to returning 27 colonial-era artifacts to Benin and Senegal. Germany has agreed to return to Nigeria priceless artefacts that were stolen during the colonisation of Africa. In 2005, Italy returned the 1700-year-old Obelisk of Axum to Ethiopia from where it had been removed in 1937 by Benito Mussolini’s troops. In 2018, Norway agreed to hand back items taken from Chile by explorer Thor Heyerdahl.

Britain remains unfazed. A British Museum spokeswoman confirmed that it even allows a “stolen goods tour”, run by an external guide. Founded in 1753, the British Museum in its mission statement, proudly states that “the Museum’s aim is to hold a collection representative of world cultures and to ensure that the collection is housed in safety, conserved, curated, researched and exhibited.” During his visit to India in 2013, when asked about restitution of the Koh-i-Noor diamond, then British Prime Minister David Cameron, had stated he did not support “returnism” since this would empty British museums.

What then is the international law of restitution, the process of returning cultural property to its country or people of origin? The 1954 Hague Convention on the Protection of Cultural Property, defined cultural property as property “of great importance to the cultural heritage of every people” and sought to raise awareness on the issue. There are subsequently two prominent conventions regarding repatriation and ownership: the 1970 UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property and the 1995 UNIDROIT Convention on Stolen or Illegally Exported Cultural Objects.

The UNESCO Convention applies only to cultural goods illicitly acquired three months after a State has become a party to the treaty- the Convention provides a framework for goods illicitly traded after 1970. It provides no legal recourse for countries seeking the return of long-lost, long-disputed cultural goods. Consequently, while United Kingdom is a signatory to the UNESCO Convention, the British Museum is under no binding obligation to repatriate its artifacts-all taken before 1970.

The UNIDROIT Convention was enacted to supplement the UNESCO Convention, to provide legal consequences on those who violated its pact. The UNIDROIT Convention states that “the possessor of a cultural object which has been stolen shall return it.” Britain is not a signatory to this convention-in fact India also is not. Only 22 countries have signed to this Convention thus far.

So, while we could not preserve our artifacts when under British rule how are we faring now? Not too well unfortunately. India has The Antiquities and Art Treasures Act, 1972 (“Act”) read with The Antiquities and Art Treasures Rules, 1973 (“Rules”) which falls within the purview of ASI. The Act was brought into force in order to regulate the export trade in antiquities and art treasures, and to provide for the prevention of smuggling of, and fraudulent dealings in, antiquities, to provide for the compulsory acquisition of antiquities and art treasures for preservation in public places .’Antiquity’ has been defined under the Act as to include inter alia a wide range of objects from any coin, sculpture, painting, any article, object of historical interest which has been in existence for not less than one hundred years; and any manuscript, record or other document which is of scientific, historical, literary or aesthetic value and which has been in existence for not less than seventy years. The Act has not been particularly effective in stopping violations.

UNESCO has estimated that India had lost some 50,000 artefacts until 1989, although experts suggest the number to be much higher. More than 1,200 ancient idols from temples in Tamil Nadu were said to have been stolen between 1992 and 2017, according to an audit by the Hindu Religious and Charitable Endowments Department in 2018. Vijay Kumar, author of The Idol Thief, estimates that atleast 1,000 pieces of antiquities are stolen from Indian temples every year. Several cases of attempted smuggling of antiques by misdeclaration have been detected by Indian agencies. With museums the world over becoming increasingly concerned over provenance of the antique before buying it, smuggled antiques invariably go to private collections which makes detection that much more difficult.

The last Performance Audit of Preservation and Conservation of Monuments and Antiquities (report no. 18 of 2013) carried out by the CAG has made a scathing indictment. The Report highlights the fact that the ASI had not conducted a comprehensive survey or review to identify monuments which were of national importance nor had they a reliable database of the exact number of protected monuments under its jurisdiction. During joint physical inspections many were not traceable. The Report states that the ASI did not have a comprehensive policy guideline for the management of Antiquities owned by it; and significantly, as the custodian of antiquities, did not even maintain a centralised database of the total number of antiquities in its possession.

What then is the way forward? We should continue to engage with countries which have our treasures. We need to strengthen the management of our heritage for which we need to know our treasures. We need to build a robust database of existing and stolen antiques and artefacts. We need to invest a lot more in our museums. It is important to increase public engagement and awareness for the protection of India’s cultural heritage. It should not be forgotten that the Directive Principles of the Constitution at Article 49 casts an obligation on the state to protect monuments, places, and objects of artistic and historic significance. Heritage it is which gives us a clue to the past, pride in our present and hope for the future.

(Najib Shah retired as Chairman of the Indian Central Board of Indirect Taxes and Customs)