By Tang Lu

When I was in India and Sri Lanka as the correspondent of a Chinese State media outlet, I would routinely plan to write about the local reading culture to mark the World Book Day on April 23. But I never got around to doing it. In this piece, I wish to share my observations on the reading culture prevalent in these two countries.

I spent about 20 years in India as a student, a visiting scholar and a journalist. After I moved to Sri Lanka in 2017, many Indian friends asked me which country was better from my point of view. Sri Lanka was certainly much more comfortable in terms of living conditions and the environment. But Sri Lanka lacked in attractive bookstores where one could browse and “pass time” as one did in India. It was also unlikely that I would meet journalists, politicians and friends in bookstores in Sri Lanka as I did in India.

In fact, when I was working in Sri Lanka, I lived in an apartment right below one of the biggest book chains in the region. But there were very few suitable books there. Every time I went to that bookstore, I felt nostalgic about Indian bookstores.

There were a few mega-bookstores in India. Some of them had changed with the times, opening counters in the posh malls. Most of the leading bookstores in India had interesting stories about them. In my opinion, bookstores are never only about selling books, they have stories to tell.

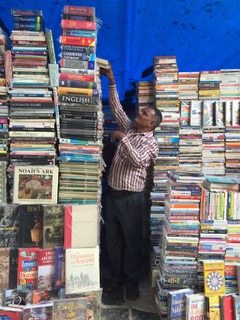

For more than 60 years, Book Street, a sidewalk on a busy street near Flora Fountain in South Mumbai, was a paradise for readers, besides being part of the city’s landscape.

At Book Street, books could either be bought or “borrowed”. From classics to the latest bestsellers, fiction to nonfiction, poetry, academic books, original prints, used books and even rare out-of-print books, this book street had everything.

There were more than a dozen vendors on Book Street. Stalls were separated by high walls, not of concrete, but books! The books here were not arranged by subject categories, as in regular bookstores, but by the size of the books.

Nilesh Trivedi owned a shop in Book Street. His father had set up the shop in the 1970s and so, as a child, he was surrounded by books. Although he went to study business at the university, he chose to join his father’s business “to be his own boss” as he put it.

Conditions in Book Street had improved a lot since the 1970s, Trivedi said. “Earlier, after closing for the day we used to carry the books home, but now there is a big plastic shed to cover our books.”

.jpeg)

“Customers are free to go to any shop they like and we shopkeepers have to give them the best service,” he asserted.

What was amazing was that the shop owners on Book Street were all extremely well informed on titles and authors and could in no time locate a title. If you named the book or the author correctly, they would quickly zero in on the spot where the book was and deftly extricate it from the “pile”. They would also recommend titles that suited your taste or interests. So whenever I went to that street, I would pick up one book after another until I couldn’t hold anymore!

If you were undecided about a book or just wanted to flip through them before you made up your mind, you could give the full deposit and return the books a few days later with a 75% refund. To me, this street of books was the equivalent of a large lending library.

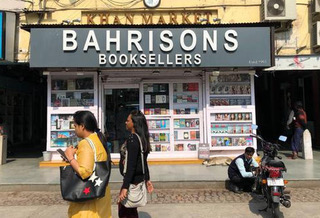

Bahrisons Booksellers, a 70-year-old bookstore, like most Indian bookstores, had a small front door that led to a floor-to-ceiling stacks of books. Despite its small space, it had a reputation for always being close to its customers.

I liked this bookstore because I could always find books on international relations and political science. And the atmosphere was very congenial. The owner was courteous to every customer. The shop’s clerk helped customers find books.

Many customers of Bahri Sons bookstore in New Dehi were members of the local elite, including politicians, diplomats, journalists and writers. The helpful clerk there was known as “Singh”. A college dropout Singh would go through book reviews and learn the reading preferences of his regular customers. He would take the initiative to reserve books that his customers might need. If he could not find a book a customer had asked for, he would get it from somewhere within the next 24 hours. Many locals described Singh as Delhi’s most knowledgeable bookseller. He was not only the highest-paid bookstore clerk in New Delhi, but also a favorite among local book lovers, with many celebrities visiting bookstores asking for his services by name!

A small group of bookstores with a highly loyal customer base were thriving in India despite the online assault on the industry. Part of the reason for their success was that they had a number of highly motivated people like Singh who also had a passion for books.

I had visited the Fact and Fiction bookstore in New Delhi often when I was studying in India in 1996. It was located on a street corner in a small in Priya Market, Vasant Vihar. The owner of the store would not put the most popular books upfront but give a list of his recommendations drawn up after doing some research. It was a place for niche books.

Every time I went to a bookstore, I would see the owner sitting at a table behind the counter, reading, or scrolling through the thick publisher’s catalogue. The owner was familiar with many of his regulars, proudly telling me during a chat that many of his regulars, including writers, academics and journalists, had frequented the store when they were young. “ And now their books are on my shelves!” he said with a smile.

In August 2015, I stumbled upon a news item that read: “It’s a sad moment when chain stores, online retail, and e-readers and tablets are gradually making corner bookstores obsolete, and Fact Fiction, one of New Delhi’s most popular independent bookstores, is closing!”

I was both shocked and surprised for, until then, I had no idea that my favorite bookstore was so famous. Vikram, the owner of the bookstore, told reporters that he chose to open the store out of his love for books. The advantage of having a small bookstore was that one could have an eclectic collection and satisfy buyers’ individual needs, he said.

On why he was closing the shop, Vikram said that books were highly tactile objects that could not be sold on the Internet alone. The bookseller could be described as a curator of books he said. This function had become redundant after images of books began to be displayed on the Internet, and readers ordered them impersonally online, and the books were delivered at doorsteps as if they were just another commercial product. Sadly, the bookstore is a vanishing species.

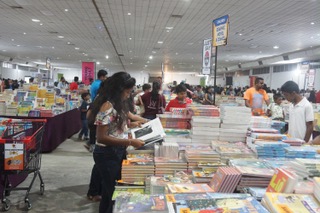

However, the good news is that with the end of COVID-19, the book market in India has started to perk up and many physical bookstores are now planning to expand. The aforementioned Bahri Sons Bookstore even opened a posh branch in a major New Delhi mall during the pandemic.

My observation is that while India does not have an overall strong reading culture unlike many Western countries, reading is very prevalent among the elite of Indian society. In big cities such as New Delhi, book launch seminars are held often, attended by the elite. Almost all of India’s English-language newspapers, mainly read by the elite, regularly feature new books and publish book reviews and excerpts.

From time to time, catalogues of books by politicians and professionals from all walks of life are also published in the Indian press. The politicians’ reading lists show that most of the books they dabble in are related to the social sciences. The elite not only read but also write a lot. Even active politicians publish monographs on a variety of subjects from time to time.

Sri Lanka has a very high literacy rate, but the reading habit has not developed well due to various factors. Sri Lankans themselves say that the lack of a broad reading culture is one of the obstacles to their country’s development and international competitiveness.

Last year, Sri Lankan parliament Speaker Mahinda Yapa Abeywardena revealed in parliament the reading interests of the country’s parliamentarians: The 225 parliamentarians borrowed only 330 books from the parliament library in 2021, of which 122 were novels, 94 were political books, 27 were on social studies and only 11 were on economics. He said he was embarrassed to say that lawmakers who needed to improve their political skills, mostly read novels. This simple statistic may also reflect the reason why Sri Lanka is so weak in governance and the country is now beset by an unprecedented economic crisis.

The old Chinese revolutionary Zhou Enlai had appealed to his countrymen to “read for the rise of China” when he was a teenager. The world is undergoing profound changes not seen in a century. And among other requirements, there is an acute need to spread the reading habit and a love for books.

END