By Charitarth Bharti/www.eastasiaforum.org

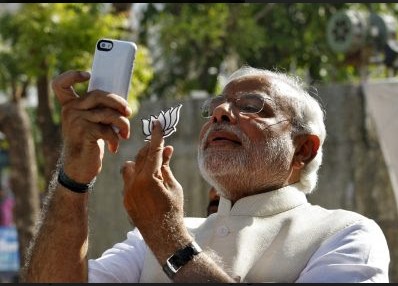

Controlling the truth is one of the most potent tools at the disposal of aspiring authoritarians. Narendra Modi’s National Democratic Alliance government in India has figured as much as it responds to the country’s humanitarian and epidemiological COVID-19 crisis, which many argue is of its own making.

Amid a crescendo of criticism from foreign and domestic observers over incompetent handling, the embattled and embarrassed government has blocked 100 critical tweets, including by opposition lawmakers, journalists and other civil society figures.

These events represent an escalating trend of suppressing free speech in India following a face-off with Twitter in February 2021. The government ordered Twitter to suspend 500 accounts and block access to several others amplifying the Indian farmer protests and highlighting the government’s poor handling. The government justification was to ‘curb misinformation and inflammatory content’. Such was the resolve of the government that when Twitter struck a defiant note — unblocking the accounts and disagreeing with the government’s assessment of the legality of the content — it served Twitter with a non-compliance notice, threatening jail for executives in India.

Behind the government’s attempts to bury the heads of 1.4 billion people in the sand over its performance is a legal regime designed to give it arbitrary and discretionary oversight over information flow. This trend has intensified since 2014 when Modi was elected to parliament and became prime minister.

Various state governments have also abused anti-terrorism legislation to suppress dissent. Most notably this includes the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act of 1967 and the National Security Act of 1980.

One legal tool the Modi government has increasingly used is section 69A of the Information Technology Act of 2000. The recent directions to block tweets and Twitter accounts were issued under this Act. The provision allows the government to block public access to an ‘intermediary’ for a swathe of vague reasons — national security, the defence of India and public order, among other things. The definition of an intermediary under the Act includes everything from local cyber cafes to telecom service providers and online marketplaces.

Requests to block accounts remain confidential, effectively preventing the public from accessing the legal document restricting access. This rule promotes an opaque censorship model absolving the government of any parliamentary or judicial accountability on censorship, despite challenges to its constitutionality before the High Court of Delhi.

The government has also sought to expand its toolkit to block content online. A recent addition to India’s censorship arsenal is the Information Technology (Intermediaries Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules of 2021. The rules were issued in February following the government’s face-off with Twitter. They seek to create an oversight and blocking mechanism for digital news media, social media intermediaries and so-called over-the-top (OTT) service providers. These rules set up a regime for ‘self-censorship’ by media and OTT platforms, failing which, government-controlled bodies retain emergency blocking powers backed by stringent penalties for non-compliance.

Among other invasive and arbitrary provisions, the rules force intermediaries to break end-to-end encryption to identify communicators on instant messaging apps — a provision over which WhatsApp has chosen to sue the government as well. The rules pose a challenge to the freedom of speech and privacy of users and represent an expansion of government power in controlling the flow of digital information. If India continues down this path, it seems to be at risk of shifting toward a China-like model where the government can break encryption to watch over citizens.

The rules also provide for social media intermediaries to deploy measures, including automated tools such as artificial intelligence (AI), to identify and remove objectionable content. This has elicited fears regarding the flaws of AI and possible encroachment through these technologies.

Another factor in this story is also what the government views as ‘objectionable’ content, and the Modi administration isn’t leaving that open to debate. Taking umbrage at Twitter moderating the online bile emanating from the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) (the Hindu-nationalist political party in power), the government attempted to bully Twitter over flagging tweets by a BJP spokesperson as ‘manipulated media’ by raiding its offices in Delhi. While the government claimed that the police were actually there to serve a notice to Twitter, the ominous signalling of two police teams where an email would have sufficed isn’t lost on political observers or the social media companies themselves.

The chilling effect on free speech under the new legal regime cannot be overstated. It violates the fundamental constitutional rights of citizens under articles 19 and 21 and limits access to information online. It deprives citizens of the basic entitlement to know what order censors them, effectively stripping them of legal remedies. India’s press freedom ranking has slipped considerably since Modi came to power and the incoming regulatory structure is set to target the last vestiges of dissent left within its otherwise pro-establishment media landscape.

These developments are not escaping the attention of India’s international partners. The United States has stated that India’s censorship policies are not aligned with the US view on freedom of speech. India needs to develop its digital rights jurisprudence to address the image it is cultivating internationally. Its strained system of checks and balances, which envisages the judiciary curbing executive overreach, must step in urgently to hold the government to account.

(Charitarth Bharti is a lawyer and a graduate of the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, National University of Singapore.)