Colombo: Today, Sri Lanka is synonymous with tea and not coffee. As on date, it is way down in the list of coffee producing countries, 43 rd. to be precise. But back in the 1870s, Ceylon, as Sri Lanka was then known, was among the top three coffee producing centers beaten only by Brazil and the Dutch East Indies, now known as Indonesia.

In the last quarter of the 19th.Century, over 111,000 hectares were under coffee in the island which exported 50,000 tons of it every year. It was the main source of income for what was then a British Crown Colony.

Subscribe to our Whatsapp channel for the latest updates from around the world

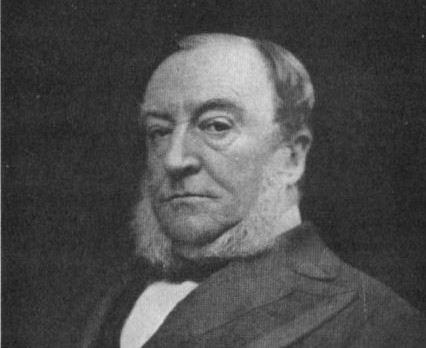

One of the British Governors who made coffee synonymous with Ceylon was Sir William Gregory. During his five year stint from 1872 to 1877, Gregory was passionately involved in economic growth, pioneering the development of plantations, roads, railways and the Colombo port. And while encouraging plantations, he did not neglect peasant agriculture. He encouraged local farmers to cultivate in succession, coffee, cocoa and cinchona in addition to paddy, and be part of the rapidly monetizing Ceylonese economy.

B.Bastiampillai, author of The Administration of Sir William Gregory, says that Gregory spent more lavishly than any other Governor on development projects. He loved Ceylon, which he described as a “glorious island” and his “darling object.”

As a matter of fact, coffee had established itself as a major commercial crop and an export commodity in Ceylon long before Gregory arrived. Investors had flocked to Ceylon from overseas and around 100,000 hectares of forest had been cleared to make way for coffee plantations. The term “coffee rush” had been coined to describe this situation as early as 1840. However, it was when Gregory was Governor that the acreage under coffee expanded exponentially.

Surprisingly, the expansion took place even as a new and unfamiliar fungal disease Hemeleia Vastatrix had begun to eat into the vitals of the crop. The fungus was destined to bring the curtains down on the coffee industry by the 1890s. However, Gregory helped the coffee sector immensely by using the surplus generated by its burgeoning export earnings to build a network of roads and railways. He built a harbor in Colombo to replace the inconveniently situated and difficult to operate one in Galle.

With new areas opening up, investors rushed to Ceylon. For example, when Gregory came in 1872, Nuwara Eliya was largely empty, but by 1874, 84,000 acres (33.933 hectares) had come under coffee there. As Bastiampillai says: the Gregory era was the “golden age” of Ceylon coffee. Higher sales and a 50% hike in the price of coffee in the 1870s in the West, brought in an abundance of cash.

Rape of forests for profit

Be that as it may, it cannot be denied that, in the initial stages, Gregory presided over a massive destruction of forests to enable coffee cultivation. The callousness of the British planters was best portrayed in a poem quoted by Richard Boyle in his article From ‘Coffee Rush’ To ‘Devastating Emily’: A History Of Ceylon Coffee (serendib.btoptions.lk). This is what the poet said about the British planter:

The ruthless flames have cleared his lands;

No trace remains of green;

When lost in thought our Planter stands,

And views the sterile scene.

In dreams he sees his Coffee spring

Fed by the welcome rain;

And berries many a dollar bring

To take him home again.

Sensing the danger from deforestation, the then Director of the Botanical Garden in Peradeniya, Dr.D.H.K. Thwaites, wrote to the authorities in Colombo and London warning that soil erosion and decreased rainfall would follow unless the cutting of forests was regulated. Thwaites’ report caught the attention of the Kew Garden Director Dr.Joseph Hooker in the UK. With the backing of the Colonial Office, Hooker sent instructions to the Governors of British colonies to stop the rape of forests. Gregory, who was exceptionally liberal in meeting the planters’ demand for land, was “warned” to take strong action. As a loyal soldier of the Crown, Gregory set about creating forest reserves. Bastiampillai notes that Gregory declared 9000 acres (3642 ha) as reserve forests.

Expectedly, the planters were livid. They got articles written in the press condemning the Governor. Dr.Thwaites was called a “croaker” and dubbed “planter’s enemy” .They sneered at the botanist’s suggestion that they switch from mono-cultural plantations to cultivating other crops also. Gregory, who was initially hesitant to deviate from coffee because it was fetching high prices abroad, was finally convinced that mono-cropping was fraught with danger. With scientific inputs and practical advice from Sir William Thistleton-Dyer from Kew Gardens and Colonial Office officials R.G.W.Herbert and R.Meade, seeds and pamphlets on diversifying plantation agriculture were distributed. Thwaite’s enthusiastic participation in this process made the Botanical Garden in Ceylon a seeds and ideas provider to several British colonies.

In 1876, Gregory opened botanical gardens in Henaratgoda to grow tropical plants which could not be cultivated at higher elevations in Peradeniya and Hakgala. His aim was not only to help the planters diversify and survive the blight, but to help small local peasants make money and improve their standard of living. In the words of Bastiampillai: “Gregory systematically encouraged, for the first time, the peasantry of the Ceylonese to take to commercial agriculture.”

In the same year, Gregory learnt that the coffee grown in Liberia in Africa, was sturdy and resistant to the disease, that it could be grown in low areas, and that Liberian coffee was fetching high prices in America. He obtained Liberian seeds and set up a demonstration plant in Pasdun Korale for the benefit of local peasant farmers. However, Liberian coffee plants also fell victim to the same fungal disease Hemeleia Vastatrix.

Cinchona cultivation

All attempts to find a cure for Hemeleia Vastatrix failed. But hope of getting round the problem was not lost. In 1860, Sir Clements Markham had secured Cinchona seeds from Peru and Ecuador in South America and sent them to Ceylon to be experimentally grown in Hakgala. Cinchona was used to extract quinine, an antidote to malaria which was then ravaging tropical lands including Ceylon. In 1873, under Gregory’s watch, Ceylon followed the example of the Dutch in the East Indies and stated cinchona plantations. Production increased, and cinchona seeds, which were given free initially, began to be sold. And sales mounted. Peasant farmers in Ratnapura and Matale also set up private nurseries to meet the rising demand.

Meanwhile in 1876, Gregory tried to get from Java, in the Dutch East Indies, better seeds known as Calisaya and Ledgeriana, but these were damaged in transit. However, the acreage under Cinchona grew from 500 in 1872 to 6000 in 1876. Interestingly, cinchona was never grown as an independent crop but only as a subsidiary one in coffee plantations. Nevertheless, the crop had played the useful role of helping planters survive the coffee blight.

Enter Tea

Although experiments to grow Assam and Chinese tea in the Botanical Garden had begun in 1845, tea became a major Ceylonese crop only in 1885. Gregory encouraged its cultivation as a plantation crop in 1872 and 1873 when he found that in England, Ceylon tea was adjudged the best. It could be grown in the higher reaches where coffee could not be.

But tea, unlike coffee, needed a resident population of workers. Fortunately for Gregory, labor was easily available from neighboring South India. By the 1874, tea growing had expanded from Nuwara Eliya to Kegalle and Ratnapura. By the 1890s, Hemeleia Vastatrix had brought the curtains down on coffee’s reign over Ceylon, and tea had become the new queen of the island.

END

For similar articles, join our Whatsapp group for the latest updates. – click here