Colombo, October 28 (newsin.asia): The Parsi community in Sri Lanka, which played a noteworthy role in modernizing the commercial sector in the island during British rule, has been fast dwindling in numbers.

Essentially a trading community which had international links, especially with India, their home, the Parsis began to leave Sri Lanka (or Ceylon as it was then known) when it came under the spell of Sinhala-Buddhist nationalism in 1956. As of date, their number in Sri Lanka has been reduced to double digits.

For similar articles, join our Whatsapp group for the latest updates. – click here

However, a recent trend of admitting offspring of mixed marriages to the Parsi faith (Zoroastrianism) may help save the community from extinction.

NewsIn.Asia is happy to reproduce here, in full, an article by historian Tuan M. Zameer Careem which appeared in Ceylon Today of June 28, 2018 giving interesting details of the Parsis’ life and contributions to Ceylon/Sri Lanka:

READ: Some facets of the history of Muslims in Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka is home to people belonging to different ethnic groups, who have lived on this island for several centuries. These ethnic groups and their distinct cultures are interwoven into Sri Lankan cultural tapestry and have each made significant contributions to Sri Lanka’s unique cultural diversity.

Howbeit, many ethnic minorities live today in ever dwindling numbers, struggling to ward off extinction.

The Parsi community is one such endogamous ethnic minority whose extinction is virtually inevitable. The Parsis, whose name means ‘Persians’, are believers of Zoroastrianism, which is one of the oldest monotheistic religious traditions in the world, founded by Prophet Zoroaster in ancient Iran, then called Persia around 3,500 years ago.

The Parsis fled Persia in the 7th and 8th centuries to escape religious persecution and made settlements in the Indian subcontinent mainly in Gujerat’s Surat Port and Bombay.

READ: Ibn Battuta found Sri Lanka fabled and multi-cultural

Later during the Colonial era, the Parsis moved to British Ceylon and became an important mercantile community in the Island. Their advent to Ceylon can be traced back to the early 18th century when Parsi immigrants from British India purchased land for commercial and residential purposes in Colombo and owned small plantation estates in the island. During the Colonial era, Parsi men worked as planters in the highlands and as merchants, particularly in the Colombo Fort/ Kotuwa.

The forefathers of this elite minority built and donated several public landmarks, too numerous to enumerate, among which is the famous ‘Khan Clock Tower’ in Pettah, which was built by Bhikhajee and Muchershaw in memory of Framjee Bhikhajee Khan, a member of Ceylon’s Parsi clan.

The Bhikhajee and Khan families also donated wards to the Colombo General Hospital and endowed prizes in economics and medicine at the University of Colombo.

In point of fact, the Hospital for crippled children known as ‘Khan Memorial Hospital’ on Ward place, Colombo was bequeathed to the nation by the Khans in 1939. Sri Lanka’s first cancer hospice was developed by Sohli Captain, a Ceylonese Parsi. Despite their small number, the Parsis have rendered yeoman services to the nation and have without an iota of doubt carved their own niche, making those rare Parsi names household ones in this country.

READ: 2021 Global Hunger Index reveals world rankings; Find out where Sri Lanka stands

On the medical front, Dr. Rustam Pestonjee served as Director-in-Charge of the Leprosy Asylum at Hendala, Dr. Khurshed D. Rustomjee worked with the anti-malaria campaign and the Cancer Society, Otolaryngologist Dr Rusie Rustomjee became the first Asian to join the Fellowship of the Royal College of Surgeons in the speciality of ear, nose and throat surgery and Dr Jamshed Dadabhoy became Chief Surgeon at the Colombo Eye Hospital.

The community has also produced several advocates, solicitors, barristers and Justices of Peace such as K. D. Choksy, Pestonjee D. Khan, F. Rustomjee, B. K. Billimoria, Norshir and Homi Rustomjee and Queen’s Counsels such as N. K. Choksy, who subsequently served Ceylon as a Justice of the Supreme Court. Dadabhoy Nasserwanji, a Ceylonese Parsi served as the private secretary to the Sultan of Maldives in 1899.

Kairshasp N. Choksy (1933-2015), was a well-known lawyer, who became a member of Parliament, Minister of Constitutional Affairs, and subsequently Minister of Finance.

Notable Educationists

The Parsi community has also produced some notable educationists. Kaikhusroo F Billimoria served as Principal of Dharmaraja College in Kandy for an astounding thirty years from 1902 till 1932. The Cricket Big-Match between Kingswood and Dharmaraja commenced in his time and he is credited to have raised enough funds to purchase the ‘Lake View Estate’ on which the College Hostel was built in 1923.

The College Scout Group began in 1914, under the patronage of Billimoria and many sports and other extra-curricular activities were encouraged during his time.

His wife, Perin Billimoria established the K F Billimoria Memorial Trust Fund for scholarships at Dharmaraja College in honour of her late husband.

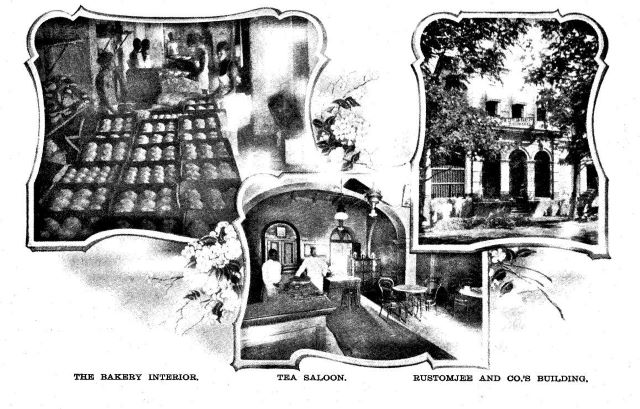

The Parsi’s acts of benevolence are legion. ‘Firdousi’, the family seat of the Rustomjees on Turret road, was used by Royal College as the science laboratory during WWII.

The ‘Framjee House’ of Methodist College (formerly the Kollupitiya Girl’s English School) was the former residence of the illustrious Framjees’s who owned ‘Colombo oil mills’ and a shopping edifice that stood on the adjoining corner of Main Street and China Street in Pettah.

Ruttonshah Rustomjee Bhoory, a well known Ceylonese Parsi commercialist donated classrooms to Wesley College in gratitude for education received. Dosabhoy Marker, a Parsi rice broker built a lecture hall for the Ramakrishna Mission at Wellawatta.

The Parsis have excelled in various fields of sports. Some of the well-known early Parsi schoolboy cricketers were R. Banajee of Royal (1912-14), his brother M. Banajee of S.Thomas’ (1914-15) and P.L. Pestonjee of Wesley College (1914-1915) who was in Ceylon’s first public school cricket team to meet a foreign side, the New South Wales cricketers (1914).

The Parsi Sports Club began as the Parsi Youth’s Sports Club in 1927, and then changed its name to its present form a year later. Since 1947, it has occupied the Parasmani Hall at 11, Palm Gove, Kollupitiya. The site was donated to the community by Framroz Rustomjee, in memory of his deceased son, Ruttonshah Rustomjee Bhoory.

The Parsis also excelled in theatre and performing arts, and had their own theatre companies. The Parsee Ripon Drama company’ that performed Shakespearean and Sinhalese plays in Colombo between the years 1911 and 1912 and the Batiwalla Natak company that performed at Colombo and Kandy in 1918, just to name a few.

Homi Framjee Billimoria, OBE was a renowned architect of Parsee origin who built a large number of official and private bungalows during the bygone colonial era.

Mumtaz Mahal (1928), the former official residence of the speaker of Parliament, Tintagel (1929) the private residence of the Bandaranaike’s on Rosmead place, Colombo 7, the Independence Memorial Hall, Colombo (1948), Kandy Masonic Temple (1951) and Navroz Baug are examples of architectural masterpieces designed by Homi Billimoria.

Acclaimed Lankan architects like Pheroze N. Choksy and Jamshed Nilgaria who served as the president of Sri Lanka Rotary Club also hailed from the Ceylonese Parsi community.

Some of the notable Ceylonese Parsis who have left their mark in Lankan history include, Perin Captain, President of SL Cancer society, Piloo M. Lakdawalla, Financial Director Central Bank, Mrs. Fredy Jilla, President of Girl Guide Association, Navy officer Homi N. Jilla, Civil Aviation officer Kairshasp N. Jilla, Army physician Minocher N. Jilla and Jimmy Barucha who was a popular broadcaster.

The Dady Hirjee (Muncherjee) was a noted commodities merchant and the first Parsi retailer who owned a shop at King’s street (later Queen’s street) Fort and the company was also responsible for palanquin facilities in British Ceylon. He was also the founding member of the Ceylon Literary Society which was inaugurated in December 1820 and donated the first set of ‘The Encyclopaedia Britannica’. The Ceylon Parsis also established the Bombay Union club in 1915 which had a well-equipped library and a reading room at Prince Street, Pettah.

The two entrepreneurial families

By the 19th century, the community was so well respected that on the formation of the Ceylon Chamber of Commerce in 1839, Hormusjee Espandiarjee and Shapoorjie Hirji were the only two non- English members invited thereon.

By 1803, Hormusjee Espandiarjee Khambata (Khambatta) was running a company at Baillie Street, Fort and imported goods from Europe and China using the three ships owned by him. Hormusjee even pioneered the processing of cane sugar for commercial use and sale in Ceylon.

Other initial entrepreneurs were the brothers Dhunjeeshah and Jamshedjee Ruttonjee Captain, whose ships sailed between Colombo, Bombay, and ports of the Malabar Coast in 1805–1812. Cowasjee Eduljee Colombowalla, was an eminent purveyor and landed proprietor who belonged to the Parsi community of Ceylon.

He was the owner of some of the largest commercial coffee plantations, the Wewassa and Debedde Estates that encompassed eight hundred and fifteen acres. He was also the owner of some of the largest ships of the time that sailed to distant lands.

The two entrepreneurial families, Pestonjees and Captains, have excelled in the field of commerce, banking and trade. The famous Abans Company was founded by Aban Pestonjee, daughter of Kaikobad Gandy, a marine engineer who worked for the Colombo Port Authority.

The Parsis, despite the turbulence of history, have preserved their unique culture, traditions, language, rites and rituals for many centuries. They are known for their peculiar surnames, typically derived either from the town or province they hail from or, their family businesses or professions.

They are well known for their cuisine which includes tantalizing delicacies like faluda, kulfi and leganu custard which are of Parsi origin.

In Ceylon, they built their own places of worship known as ‘Navrose Baug’ (‘New Year Garden’), and the ‘Agiari’ or fire temple which is located on Fifth lane, Colpetty. The Parsis have an interesting way of naming their children and is based on the date and time of the child’s birth.

They even have their own initiation ceremony known as Navjote, the ritual through which a Parsi child is inducted into the Zoroastrian religion and begins to wear the Sedreh (sacred shirt) and Kushti (sacred girdle). A unique feature in the Parsi funeral is the employing of a ‘four-eyed dog’ which is allotted some funerary ceremonies analogous to those of humans.

As part of the Parsi ritual known as ‘sagdid’, two markings are drawn above the dog’s eyes (on the forehead) and it is led to the corpse. If the dog turns away from the deceased, it is certain that the person is dead.

The Parsis also believe that the gaze of the dogs’ wards off black magic and evil spirits. In the Zoroastrian tradition, once a body ceases to live, it can immediately be contaminated by demons and made impure and should not be allowed to pass on its impurity to the elements around it, especially the element of fire, which is believed to be holy.

Thus, dakhmas, or Towers of Silence, were built for laying the dead to rest. The first Parsi dakhma or funerary Tower of Silence was built on Bloemendhal Road, Kotahena and the property was deeded to the community in 1826 by Cowasjee Eduljee.

The dakhma at Kotahena was circular, raised white structure on which excarnated bodies of deceased Parsis were exposed to be devoured by vultures and carrion crows or desiccated by the sun.

But within a few years, the Parsi’s practice of excarnation of the dead-faced severe criticism from the residents in Kotehena who opposed the idea of exposing corpses to vultures on top of flat-topped towers.

The Parsis in Ceylon later adopted the practice of inhumation on the same property but after 1861, the dakhma and aramgah (place of repose) at Bloemendhal Road were closed and walled off. Cowasjee Eduljee funded the construction of the wall and the community retained control of the site until 1967 when it was sold.

In 1887, two and a half acres were obtained from crown land in Jawatte, Cinnamon Gardens and the Parsis built their funerary tower, a caretaker’s residence, storage room for biers, ossuaries, well of silence and place of repose. The structures are still standing and the cemetery is still in use.

The total population of Zoroastrian men, women, and children within Sri Lanka numbered approximately 61 in the year 2006. The Parsi community in Ceylon is on the brink of extinction, due to intermarriages, migration to foreign lands and mainly because of the fact that they do not accommodate offspring of mixed unions into their community.

As they are a strictly monogamous and endogamous group, there is high Frequency of Factor V Leiden Mutation and other genetic disorders in the community. Alas, there are now only forty five Parsis left in Sri Lanka and as Parsi custom doesn’t allow outsiders to marry in, their future seems DOOMED.

END

WATCH: Shah Rukh Khan shares powerful message in Cadbury’s viral Diwali ad

Subscribe to our Whatsapp channel for the latest updates from around the world