By Dr.Lopamudra Maitra Bajpai

Chewing “bulath” or betel leaves is an ancient tradition across South and South-east Asia and also some parts of the Pacific. And with the practice of chewing betel leaves came the designing of betel containers or bulath bags.

Over time, from ancient times, the use of betel leaves became ritualized. It got incorporated into religious systems. Additionally, the bulath leaf became a symbol of social reciprocity and respect. Chewing betel in company is standard practice in social gatherings, even today.

Betel was traded internationally. It brought about cultural connections across regions over land and over seas. The story of betel containers also brings out the cultural milieu and cultural connections.

In Sri Lanka, containers are primarily made of cloth and are known as ‘Bulath Bags’, which over time had associations with, and showed influences from, across the Indian sub-continent.

There is historical and archaeological evidence in Sri Lanka about the use of bulath and bulath bags.The bulath bags had doubled up as a purse and served many other purposes. The Sinhalese Dictionary of the Department of Cultural Affairs mentions several uses of bulath and its containers.

Sri Lankan literature mentions the use of bulath at the time of King Kavantissa (161-137 B.C.), the father of the celebrated King, Dutugamunu. Betel leaves were offered to Buddhist monks at that time (see Sahassavattuppakaranaya edited by Aggamaha Pandit Venerable Buddhadatta Thero in 1959 and mentioned later by Francis Bulathsinhala in 1991). In the ancient inscriptions too, there are references to the use of bulath – the earliest mention being in the inscription of King Kith Sirimevan (303-331 A.D,- wherein the word Vetayala is used. Incidentally, Vetalaya is the Tamil word for the betel leaf. The second mention is in the pillar inscription of King Udaya IV (946-954 A.D.) at Badulla.

Archaeologically, there have been evidences of clay and bronze lime boxes dating to 12th century A.D. from Paduvasnuvara, Jetawana Dagaba site, Anuradhapura and Polonnaruva.

At present, the Colombo National Museum has, in all, more than seventy betel bags. Treasured as an important historical art from, these ornate bags are a significant aspect of the cultural heritage of Sri Lanka.

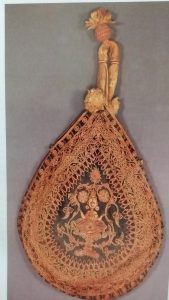

A typical cloth betel bag is called Bulath-Payiya. This consists of two or more handles. These handles are mostly plaited through cords or woven bands. It is to be noted that these ornate cloth bags are mostly from the late-Kandyan period (across the last few centuries), by which time Sri Lanka had established trading contacts with other countries, especially India.

Interestingly enough, the weaving pattern of the straw bulath bags bear a close resemblance to embroidery patterns found in various parts of India. There are small bulath cloth pouches of a similar pattern in Odisha in Eastern India. The ornate knots and stitches also bear a close resemblance to the chain stitches used extensively across North India, especially from the Medieval period (roughly 4th-5th century) onwards.

The ornate applique as well as the running stitches bear a close resemblance to the famous ‘kantha stich’ or running stitch in West Bengal (India) and Bangladesh. The innovative touch however comes through the conceptualization and execution of the design which imparts a special regional touch and makes these bulath bags unique.

A common feature across most of these cloth bulath bags is the lotus, but variously expressed through different stiches and colours.

Mostly made in velvet, silk or thick cotton cloth, the silk thread designs have a common set of colors including, yellow, golden, red, light and dark blue and white.

When blue cloth was used, the embroidery used to be done in red and white threads, and when it was on white cloth- it was mostly red and blue threads. There was a central design- a flower or a floral pattern. In later years a deity or a goddess was sewn- like Shri or Lakshmi. The two sides of the bags generally had the same design and the central figure was framed with several borders, which varied between liya vela and kundirakkam, diamonds, squares, havadiya, pala-peti and bo-pat.

The size of the bulath bags varied, as the collection in the Colombo museum shows. Some are large, around 75 cm, while others are as small as 15 cms. The small pouches used by women are called ‘hambili’. Those used by men are referred to as ‘bulat-payi’. Bags with handles are referred to by various names such as ‘bulath-payi’ (purse or pouch), Bulat-malla, Kokkanama, Kurapayiya and Bulath-olaguva (P.H.D.H. De Silva and M.M. Dayananda Peiris)

In 1807, Cordiner mentioned the variety in bulath bags and also the reason for the variety. Small wallets made of colored straw, the ‘pan’ grass, Kukul vel or simple cloth were generally used by the poorer sections of society. This shines a light on social usages. In the middle of 19th century ,some writers stated that silver or brass bulath bags were hung at the waist “enclosing a smaller one to hold a portion of chunam, while the larger contains the nuts of the areca and a few fresh leaves of betel-pepper” (Tennent-1859).

(The author is a Research Grant Fellow of India-Sri Lanka Foundation and was Culture Specialist at the SAARC Cultural Center in Colombo)