By Dr. Lopamudra Maitra Bajpai

Alec Guiness, the British stage and film actor once asked: Who is more foolish? The fool or the fool that follows him? The answer to this is tricky, as both the leader and the follower share a unique bond of mental compatibility, built on their own world of experiences which are logical to them, but foolish to the rest of the world.

Oral traditions and folklore the world over have stories of fools. In some, he is a village-idiot, and in some others he is a “wise fool’ who is often consulted for his out of the box thinking. At other times the fool is a leader or a ‘teacher’ with a group of followers.

Stories of erudite ‘teachers’ seem to have been part of folklore throughout the Indian sub-continent and its neighborhood.

Across southern, south-eastern and north-eastern parts of the Indian subcontinent and even beyond, the erudite fool is famous. In Sri Lanka, he is famous as Maha Daena Muththa. In south and south-eastern India he is Guru Paramartan, Gooroo Noodle and Guru Simpleton and as Niret Guru in and around Bengal.

Tales of wit and satire, the adventures of the Guru and his disciples reflect a cross-cultural connection across South Asia.

The stories were first compiled during British rule and seem to have originated in southern India and travelled further up across the eastern parts till the north-eastern region. They then travelled down to Sri Lanka.

Compiled and published by Sita Devi, the Bengali version of the stories was released around the second decade of 20 th. century. This set of stories is centered around a teacher Niret Guru and his five disciples. This book is titled ‘Niret Gurur Golpo’ (The Stories of Niret Guru). Sita Devi actually translated this from the English set of stories titled ‘The Adventures of Gooroo Noodle’ by Benjamin Babington (1794-1866 of the Madras Civil Service, published in 1915 by Panuini Office of Allahabad).

The English translation was from an original work in Tamil. That revolved around a foolish man and his five disciples and was part of local lore. The book “Guru Paramartan” was compiled by the Italian priest and scholar, Constantino Giuseppe Beschi (1680-1747), who knew Tamil well. Beschi was called Viramamuni by the Tamils. He had been appointed by the Pope to the East India mission in 1700. Beschi’s book was published in London and the following year, it was distributed in Madras. Benjamin Babington translated eight of these stories that show the comical side of a teacher and his disciples.

As Stuart H. Blackburn notes in his “Print, Folklore and Nationalism in Colonial South India” this was an “example of Tamil folklore in print”. The publication helped streamline grammar and expressions and paved the way for further local publication.

Beschi’s selection of stories also helped contribute to bilingual grammar and inter-lingual dictionaries, script reform, translations and discursive prose. As Blackburn these translations laid “the foundations of understanding language as a human artifact and of literary forms as a tool for cultural change….and also understand and answer new questions of what kind of Tamil to write, what it should look like and what textual forms it might assume after the introduction of the printing press in India.’

The popularity of the collection of short stories went on to create many more versions of this humorous book across India in the English language especially 1845 onwards.

Similarities between the stories are evident. The Bengali names of the five disciples are Akat, Haba, Hada, Boka and Ahammak (varying synonyms of a dim-witted person in Bengali). The English names in Babington’s book are, Blockhead, Idiot, Simpleton, Dunce and Fool.

Sita Devi’s Bengali work encouraged other versions in English as mentioned by J.D. Anderson. “Miss Sita Devi has recently published in the Bengali language, a delightful little volume of folk-tales entitled Niret Gurur Kahini, composed chiefly of the misfortunes which befell a simpleton Brahman called Niret, and his five disciples.”

It was around that time, in 1920, that Anderson had also published his collection of stories of the teacher and his five disciples in English under the name “The Six Simpletons and Other stories”. A mention of this found a place in the Folklore Journal in 1920 (A Quarterly Review of Myth, Tradition, Institution, & Custom being The Transactions of the Folklore Society and incorporating The Archaeological Review and the Folklore journal vol. xxxi.—1920, London- Published for the Folk-lore Society by William Glaisher, Ltd., 265 High Holborn, London, W.C., 1920 [lxxx.] and printed at the University Press at Glasgow by Robert Maclehose and Co. Ltd.).

What is interesting is that the same set of stories of the teacher and his followers had appeared across north-eastern India. Anderson notes as early as 1886, that he had heard the same set of stories in the Bodo or Cachari language of Assam.

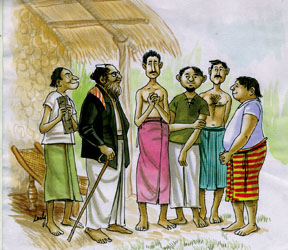

The Sri Lankan counterpart of the Guru is Maha Daena Muththa. Though the exact date of the Guru’s origin remains to be researched, he seems to be having a colonial origin seeing his many adventures. He is described as a man of ‘repute’. He has long hair tied in a bun and pulled together with a tortoise shell comb. He has five pupils who are wittily named to suit a physical feature or a behaviour of theirs. They are Idikatu Pencha (tall and thin and looked like a big needle), Puvak Badilla (a thin face and looked like an arecanut tree), Polbe Muna (had a face that resembled a half coconut), Kotu Kithaiya (thin and looked like a stick) and Rabboda Aiya (big tummy or a toddy belly).

What is interesting is the fact that within each of these sets of stories the representation of the protagonist, the teacher or the Guru, reflects the local population and is associated with its socio-cultural ethos.

In most stories, there is also the representation of a horse. There is also a portrayal of futility. All attempts by the Guru and his students to get a horse so that the teacher might travel in comfort, meet with disappointment. Finally, when they do succeed in getting a horse, the situations that crop up are always troublesome and the horse brings the opposite of what the owner desires.

The “wise fool” is often a teacher. When the Guru was travelling with his five disciples, his turban (described in the Sinhala version as his tortoise-shell comb) fell off his head. The Guru noticed it only a few minutes later and was surprised that none of the disciples had picked it up. Their lame excuse was that they were not instructed to pick it up! The Guru then gave them a list of items to pick up in case they fell down and they diligently noted it down in their books. These items included- the master’s comb, his coat, his sarong, his bag, his umbrella and his walking stick. Since it had rained the night before, the horse on which the Guru was travelling tottered and fell. As the Guru lay in a deep puddle of mud asking for help, the disciples refused to pick him up stating that in their book there was no instruction to pick up the Guru if he fell down. Finally, the Guru had to take the book and add this on. It was then that the five disciples picked him up and washed the mud off his aching body and took him home,