New Delhi, April 29 (www.yourstory.com/India Today): Countries across the world have shown solidarity with India and its citizens — sending medical equipment, ventilators, and oxygen tanks, and concentrators, among other aids in large numbers.

But, the country itself is rallying together to fight this deadly second wave — one step at a time.

From preparing home-cooked meals for COVID-19 patients in quarantine to helping allocate oxygen cylinders, and ICU beds for more serious patients — in almost every corner of the country — Indian citizens are stepping up to help each other.

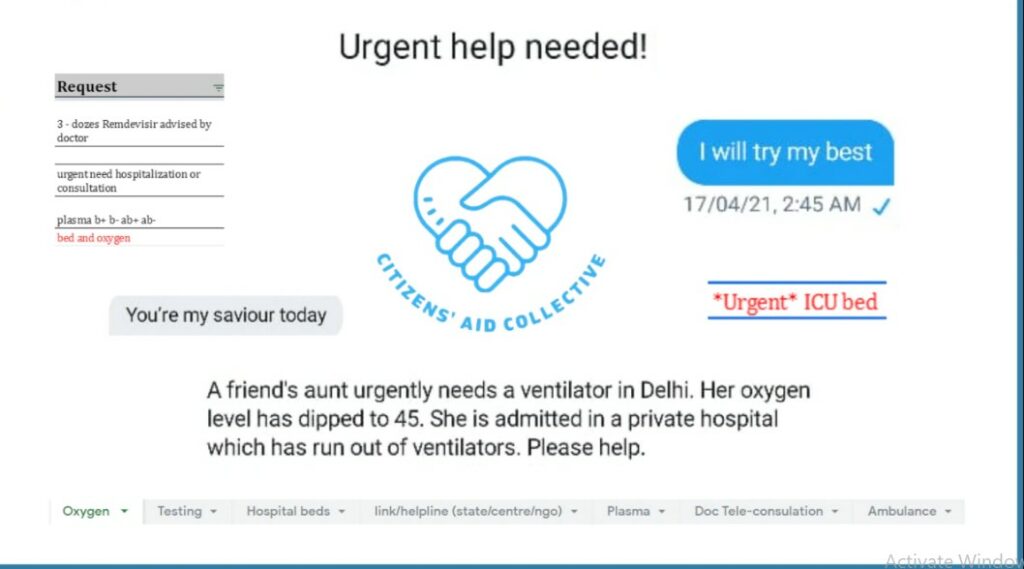

India is surviving on acts of kindness, amplified on social media platforms like Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and WhatsApp, where requests for hospital beds, medicines, injections, plasma, and oxygen are flowing, and sometimes, overflowing.

Gritty COVID Volunteers

In his touching story in India Today dated April 30, Meghnad Bose writes about Kaushik Raj and Aanya and others, brave COVID fighters in New Delhi:

“I feel guilty even going to sleep. There are so many calls and texts asking for help, how can I just leave them unattended and go to sleep?” asks 22-year-old Kaushik Raj, who has been volunteering to help Covid-hit families get access to the healthcare services they need for the past fortnight.

Kaushik, a fourth-year engineering student and poet in Delhi, has been working up to 21 hours a day, everyday, helping save lives. “I fall asleep only when it is impossible to keep my eyes open anymore. I sleep by around 4.30 am, and am up and working again by 7.30 am.”

He is one among hundreds of citizen volunteers across the country who are doing everything they can to help with Covid aid and relief efforts. But now, many of these volunteers are scared that state authorities will come after them on some false pretext or another, and as a result, multiple volunteer groups have shut down and stopped the crucial work they were doing.

But more on that in a bit. First, let’s take a look at how exactly these volunteers help families in dire need, and that too by working remotely.

Kaushik explains his process with an example, “I saw a tweet on my timeline, it was from a woman living in the United States.” Janvi (name changed) needed help for her Covid-positive mother who was in Delhi and needed urgent hospitalisation.

Kaushik continues, “I reached out to her and began calling different hospital authorities in Delhi to check if they had a bed available. Eventually, Lok Nayak Jai Prakash Narayan (LNJP) Hospital told me they did. I spoke to the nodal officer of the hospital and verified it myself. I messaged Janvi and informed her immediately.”

Janvi’s mother was admitted to the hospital soon after. A grateful Janvi messaged Kaushik, “Thank you so much, Sir. You’re my saviour today.”

How had he begun doing this work though, to respond to SOS calls on social media and help complete strangers?

“Around 14th or 15th (April), I started seeing a lot of SOS calls on Twitter. Initially, I just started retweeting those calls. Then seeing my retweets, people began DMing me asking that I share their SOS request too. A few of us friends then began helping people find resources like oxygen, hospital beds, etc. at an individual level.”

But as the crisis of the second wave got bigger and bigger, with lakhs of cases everyday, thousands of deaths, and a crumbling healthcare infrastructure, Kaushik and his friends decided they needed to ramp up their efforts manifold.

“We thought to ourselves – instead of doing this separately, it’ll be so much more impactful to get together and make a helpline of sorts – here are the requests, here are the resources, and we will help match the requests and the resources. There were around 10 of us in the core team. But then once the helpdesk started, there were more than 100 volunteers who joined in.”

Kaushik and his fellow team members at Citizens’ Aid Collective built two spreadsheets for their volunteers. The first spreadsheet contained the various SOS pleas that needed to be catered to. This also included the responses that came in through an SOS Google form that they had made and circulated.

The other spreadsheet had a constantly-updated list of leads about resources such as oxygen cylinders, hospital beds and medicine availability. The team would only post leads on this sheet after verifying it themselves.

Volunteers would then match the requirement mentioned in the SOS sheet with the verified leads available on the resource sheet.

Kaushik recounts, “We had seen an SOS for a 75-year-old woman named Priyanka Jain (name changed) who was in a critical condition in Delhi. She urgently needed to be moved to a ventilator bed in a hospital. I sent our verified leads to the contact mentioned in the SOS and we were able to get a bed for her.”

“Now she is fine,” he added as a happy afterthought.

A fellow core team member of the Covid helpdesk, who did not wish to be named, added, “We had started off very ad-hoc, but within three to four days of the helpdesk, we were able to put an organisational structure in place.

There was one WhatsApp group where SOS calls would be posted, and another group was for managing the resource sheet – that was divided into three sub-groups – one group to source new leads, another to verify those new leads and a third group to verify existing leads. Then there were individual groups for oxygen, medicines, plasma, hospitals, and RT-PCR testing.”

Aanya, a third-year student at Lady Shri Ram College in Delhi, began a Covid aid initiative called Covid Fighters India, which has actively provided assistance to hundreds of patients’ families over the past several days.

Speaking to IndiaToday.in, Aanya says, “Around 17 April, a friend of mine, Arnab, and I realised that a lot of people had started making SOS requests on Instagram but that a lot of those messages weren’t reaching the right target audience, the people who can help them with their requirements.”

She adds, “We started by making a Discord community, which now has more than 8,000 people who keep helping each other. But soon, we realised that there was such a huge flow of information, but that information wasn’t verified, so somebody who has an emergency will not have the time to go through so many numbers and so many links. So, they need one pitstop for the resources which are already checked by someone else. That is when I started the verification process in our team.”

Together, their team created one master Google spreadsheet containing verified and updated resource leads. The spreadsheet was then shared widely and amplified on social media. Everyone could view it, but only the Covid Fighters India team could update the leads on it.

“Every resource on the spreadsheet gets rechecked and updated every three hours,” says Aanya.

Their team is also leveraging technological aids such as a Twitter bot to help them in their efforts. “We’ve started a Twitter bot which we’ve got approved by Twitter. We have a Google form for people who need plasma, so what happens is that the moment someone fills up the form, the bot automatically tweets out the request and tags many of the organisations working on plasma.”

Given the hundreds of cases they are trying to provide assistance to amidst this burgeoning crisis, the core team of Covid Fighters India has now grown to around 50 people. Apart from them, there are 200-300 volunteers who join in on the work every day.

The leadership and administration skills that an initiative of this scale requires are mammoth too. But youngsters like Aanya and Arnab have risen to the occasion. Aanya remarks, “We have different team leads for hospital beds, medicines, oxygen, doctor resources, food resources, etc. The team leads have different slots of the day assigned to them.”

Despite all their efforts, though, there are times when they just can’t help.

“There was someone who contacted me via Instagram,” says Kaushik. “She needed a bed for her 80-year-old grandmother. I tried absolutely everything I could – I called various hospitals, other resource people who were helping relief efforts – but it was one of those occasions when we just didn’t get a positive response from anywhere.”

He adds, “Eventually, she messaged me saying, “It’s okay. What matters to me is that you, a complete stranger, who doesn’t even know my nani, tried just as hard as I did to find her a bed.”

Aanya recounts, “There was this person, Anjali (name changed), who got in touch with me on Instagram. She messaged around 1 am, asking me if I had any lead for oxygen in Delhi – she needed it for someone’s father. It’s very difficult to get oxygen so late at night. I tried checking the various WhatsApp groups for any lead that may have come in and then I sent her some of the leads. She got back to me after a while and said that she had managed to get the oxygen.”

But the crisis wasn’t over yet.

A while later, there was another urgent message from Anjali. They now needed an ICU bed because the patient’s health had deteriorated further.

“Raat ke do-teen baje ICU bed milna na ke barabar hai (nowadays, looking for an ICU bed at 2-3 am feels like it’s destined for failure). It’s a miracle if you find one. But I sent her leads that we had verified just that night.”

And then Aanya waited for the response. Around 4 am, before she was going to call it a night, she texted Anjali to check if there was an update. There was no response.

“When I woke up in the morning, I saw a message from her. It said “He is no more now.”

“Because I’ve been constantly working, I don’t have time to process all of my emotions. But one of these days, I realised that it doesn’t matter if you help 30 people, what hits you more is the 15 people you couldn’t help. That’s when I felt completely helpless.”

Even as she helps fight a public health crisis, the toll on the mental health of volunteers like her is immense. Aanya laments, “You don’t know who to hate – do you hate yourself for not doing enough? Do you hate yourself for not finding enough leads? Do you hate the fact that there just aren’t enough leads out there?”

“I couldn’t process my emotions or spend time feeling bad about it, because there were so many other people who needed help that morning. I think there’s no option for us to have a breakdown – because if we start having breakdowns, jitno ki help ho rahi hai, woh bhi nahi hogi (even those who are getting helped right now won’t get that assistance).”

But it isn’t always possible to remain stoic, and sometimes, the emotions just burst through.

“I have broken down in tears on so many occasions in these past few days, almost every single day,” says Kaushik Raj.

He recalls a recent conversation, “Someone I had been helping with leads on ICU beds called me angrily and said, “Don’t bother helping now, the patient is no more.” I heard him out because I could understand his anger. I could only tell him that I’m sorry.”

“It stayed in my mind, and I have been thinking about it for so long,” he adds. “People would call and text us with so much hope, but the resources themselves are so limited. I felt helpless.”

Muskan Shandal, a 22-year-old journalist based in Chandigarh, has been working tirelessly to verify leads and send those crucial updates to those in need. She says, “In Chandigarh, a family acquaintance’s relative needed to be moved to a hospital bed with a ventilator. I had a lead which I had verified, and I passed it on to the patient’s family. The bed would be provided along with proper medical attention, but a ventilator was not available.”

A while later, they got in touch with her again and said, “Muskan, please see if you can manage to find a ventilator for her.” She told them, “Give me 10 minutes, I’ll get back to you.”

“I was just getting done with my shift at work,” Muskan explains. “Right after, I quickly checked with someone else and provided them a lead for a ventilator. But right then, I got two messages on WhatsApp – We have lost her. Thanks for all your help Muskan.”

Despite everything she is doing, shuffling from her work as a journalist to her efforts to help people locate Covid resources, Muskan is still filled with regret for not responding “ten minutes sooner” – even as she deals with tragedies closer home.

Three of her close friends have recently lost their mothers to Covid-19. And even as this article was being written, Muskan sent across a message saying that her grandfather had just passed away. She posted a story on Instagram saying, “I will be off social media for a day or two. While I genuinely want to be a part of helping everyone in whatever way I can, I have to take this time off to be there for my family.”

An Unattended Mental Health Crisis: The Toll It Takes on Volunteers

When a friend had suggested that Kaushik start seeing a therapist to cope with the toll this crisis was taking on his mental health, he had replied that it was only a matter of a few more weeks. “They are saying it’ll be this bad for around 20 more days, right? So, let me work for these 20 days, there will be time for therapy after that.”

He adds, “If I do something else, even for a little while, I think, “Koi SOS de raha hoga ab (somebody must be sending an SOS right now). That’s why I would not do any work which I felt would take away time from doing this (volunteering). I even stopped taking a bath for three to four days, thinking that in those minutes too, I would be able to deal with so many SOS calls instead.”

Aanya echoes a similar sentiment, “For the past ten days, we have been working on a 20-hour-shift everyday. My day starts at around 8:30 in the morning and goes on till around 4 am. A lot of emergencies come in between midnight and 4 am, so we have to definitely keep working at that time.”

While Down With Covid Or During a Board Exam, ‘The Volunteering Must Go On’

“I had my pre-board this morning,” says 18-year-old Aarushi Koul, a Class 12 student of Delhi Public School, Noida. Her Fine Arts exam was conducted online on 27 April, from 8:30 to 11:30 am. “The moment I finished my exam, I started working.”

The work she is referring to is in her role as a Team Lead of the Oxygen sub-group of Covid Fighters India. Aarushi says, “Even during my exam, I was constantly WhatsApping people, sending them leads on resources, and responding to individual requests for help.”

Many of the volunteers have continued work even when the crisis has hit home, or even themselves.

Aarushi says, “One of my friends is down with Covid at home but he’s still volunteering and working on re-verification of resource leads to help others. Another volunteer, Chhavi, continued working even when she and her family members were Covid-positive. She was volunteering from home even when she had a fever.”

And Then, The Fear

Even as the healthcare crisis worsened, and more citizen volunteers rushed in to help those in need, a sudden fear gripped volunteers, sparked off by testimonies on social media that claimed that the Delhi Police had made calls to their fellow volunteers, warning them that sharing information about oxygen, medications, etc. contributes to the black market.

The Delhi Police on their part vehemently denied the allegations and said they were being “levelled by motivated elements on social media.”

END