By Vinod Moonesinghe/Factum

Colombo, January 30: A 2002 poll carried out by the BBC, accompanying its TV series “Great Britons”, found that most viewers fancied wartime Prime Minister Winston Churchill as the “Greatest Briton”. His sole claim to fame lay in making stirring speeches when the British Empire stood on the threshold of defeat.

Yet his pro-US policies and inflexible opposition to de-colonization led more to Britain’s decline than any action by any British leader before Margaret Thatcher. His peacetime praise of Hitler, and his blaming of the Jews for Nazi anti-Semitism, show his allegiance to the concept of Empire, rather than to the British people. The selection of such a racist, imperialist bigot says much about modern British historiography and the power of the media.

The respondents also selected Horatio Nelson, Duke of Bronte, in ninth place. The admiral, who has long graced the pages of British imperialism and of English national pride, laid the foundations for the century-long Pax Britannica with his posthumous victory at the 1805 naval Battle of Trafalgar. His contemporary Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington, whose defeat of Napoleon Bonaparte at the 1815 Battle of Waterloo began Britain’s 99 years as “sole superpower”, did not make it into the top ten.

Plassey to Assaye

The British Empire which Churchill espoused so fiercely and anachronistically might not have existed, at least not in the form it did, without the victories of Nelson and Wellington. A grateful British establishment rewarded Nelson’s memory with a 5.5 metre statue, atop an eponymous, 46-metre column at Trafalgar Square; and Wellington’s by the massive, Romanesque Wellington’s Arch at Green Park (both in London).

But these victories in turn might not have been possible but for the actions of an obscure English East India Company (EEIC) commissary lieutenant, Robert Clive – who never made it to the BBC’s list of 100.

Clive should probably have been credited as the true founder of the British Empire. He later received an Irish peerage as Lord Clive of India, mainly for defeating the French-influenced Moghul Nawab of Bengal Siraj Ud Daulah at the Battle of Plassey (Palashi) – described famously by eminent historian K. M. Pannikar as “a transaction, not a battle, a transaction by which the compradors of Bengal… sold the Nawab to the East India Company.”

This 1757 victory apparently sealed the fate of India, although the EEIC had many subsequent setbacks, and many struggles on its journey to paramountcy over the subcontinent – which it achieved by Wellington’s defeat of the Maratha Confederacy at the 1803 Battle of Assaye.

However, the importance of Plassey cannot be gainsaid. During the 18th century, India may have been the world’s richest country, even surpassing China, and accounted for an estimated 25% of the world’s industrial production; Britain accounted for just 2%. Its acquisition by Britain made it more than just the “jewel in the crown”, but the “crown” itself.

The economist Utsa Patnaik, reviewing nearly two centuries worth of data, estimated that between 1765 and 1938 the British extracted (by what Karl Marx called “primitive accumulation”) from India about US$ 45 trillion in wealth, equivalent to 17 times the United Kingdom’s current GDP.

According to economic historian Angus Maddison, the process impoverished India, plunging its world GDP share from 27% in 1700 to 3% in 1950. This wealth, together with that from slave labor in the West Indies, drove the Industrial Revolution, making Britain “the workshop of the world” and providing it the wherewithal to fight more wars.

Low ebb

Plassey had a prologue, six years earlier. The Mughal Empire, in terminal decline, had lost control of its southern satrapies. A nominal Moghul subordinate, the Nizam of Hyderabad, ruled over the dominions centred on Hyderabad. Another, the Nawab of the Carnatic, legally a deputy of the Nizam, ruled over the eastern seaboard.

In 1749, an ally of the British, Muhammad Ali Khan Wallajah, became Nawab, but Chanda Sahib (Husayn Dost Khan), a relative of the previous Nawab and a French ally, defeated him, and he sought refuge in Tiruchirappalli (“Trichy”). Two years later, Chanda Sahib besieged Wallajah there.

Prospects for the EEIC looked grim. Just one of several European powers trading in India, it operated out of four ports, Mumbai, Kolkota, Chennai, and Cuddalore, and relied on alliances with local rulers to maintain its position. Only its hold on Mumbai remained secure. In 1746 the French captured Madras and laid siege to Cuddalore, and later to Kolkata.

Only European peace saved these British entrepots. The Company’s directors anticipated abandoning the whole of South India to the French, whose growing influence had caused the British plight. Had Chanda Sahib taken Trichy, the British Indian Empire might never have existed.

With EEIC fortunes at their lowest ebb, up stepped Clive, then just 26. Having joined the EEIC as a “writer” (clerk), he joined the EEIC army in Cuddalore after escaping the 1746 French capture of Chennai. He received a commission as an ensign for his part in repulsing the subsequent French attack on Cuddalore. He had distinguished himself during an abortive siege of the French fort at Puducherry (“Pondy”), and in the ignominious failure of a British attempt on Tanjavur. The Company had promoted him to Lieutenant.

Arcot

Two centuries before Basil Liddell Hart’s theories became a reality, Clive advocated the strategy of the indirect approach. He proposed to lead a small force from Chennai to Chanda Sahib’s capital, Arcot (Ārkāḍu), to force him to raise the siege of Trichy. The EEIC Governor of Madras, Thomas Saunders, gave him 200 European and 300 Indian troops, three guns, and a commission as captain.

In five days, Clive’s half-battalion marched 111 km, including through a severe thunderstorm, arriving at Arcot on 11 September 1751. The garrison, twice the strength of his force, decamped in awe at the feat. Clive swiftly occupied the abandoned fort and began repairing the derelict fortifications.

Joseph François Dupleix, governor for the French East India Company advised his ally, Chanda Sahib, to concentrate on the speedy capture of Trichy. However, the latter sent his nephew Raju Sahib with 4,000 of his troops to besiege Arcot. This host, augmented to 7,300 Indian and 120 French troops, with guns and elephants occupied Arcot town on 4 October and invested the fort.

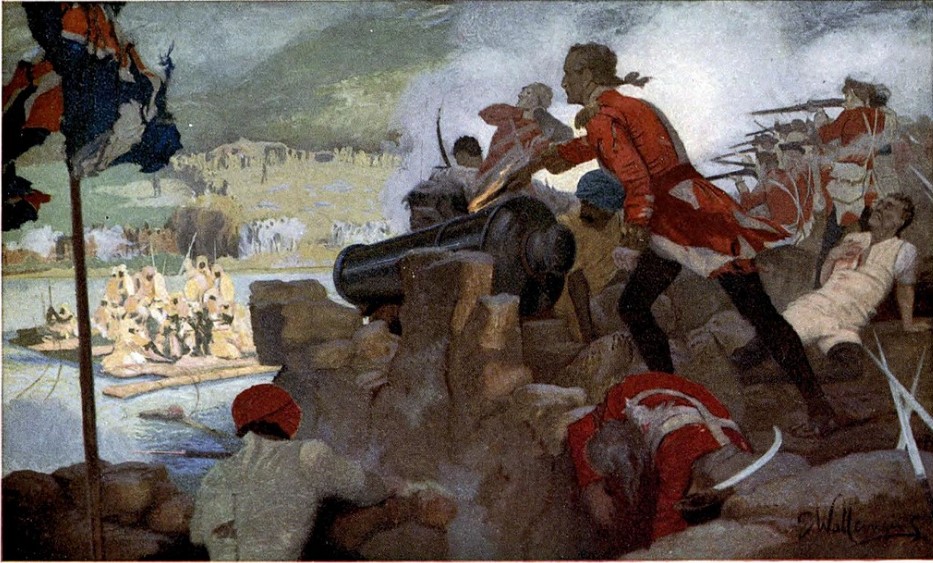

Clive’s tiny force held out against this mighty army for 52 days, being reduced to fewer than 200 by the end, with the ramparts battered to rubble by Raju Sahib’s 18-pounder guns. On the last day of the siege, the British held off a massive attack, firing 12,000 musket shots in an hour. The next day, Raju Sahib raised the siege and departed for Vellore.

The plucky defense had piqued the imaginations of India, and the Marathi General Murari Rao Ghorpade had come to the aid of the defenders with 6,000 men, forcing Raju Sahib’s retreat.

This marked the turning point of the EEIC’s fortunes. Clive’s defense of Arcot, his subsequent defeat of Raju Sahib at the Battle of Arni and his capture of Kanchipuram, enabled the relief of Trichy the following April, and the reinstatement of Wallajah as Nawab.

These victories won through luck and treachery as well as skill and courage, gave the British an invaluable reputation for military skill on the subcontinent. Without them, the EEIC might not have been able to recapture Kolkata from Siraj Ud Daulah or to defeat him at Plassey. In short, Clive’s victory at Arcot enabled the British to establish their Indian Empire: a feat that should place him at the top of any “Greatest Britons” list, insofar as this title reflects imperialist nostalgia.

END

Author Vinod Moonesinghe read mechanical engineering at the University of Westminster, and worked in Sri Lanka in the tea machinery and motor spares industries, as well as the railways. He later turned to journalism and writing history. He served as chair of the Board of Governors of the Ceylon German Technical Training Institute.