By Kanishkaa Balachandran/The Hindu

When Wing Commander Abhinandan Varthaman’s MiG 21 was shot down by Pakistan in February, he ejected and was soon captured. He was released as a goodwill gesture nearly three days later and returned to a hero’s welcome across the border.

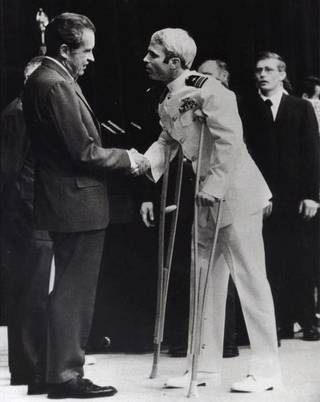

Over 51 years ago, Lt Commander John McCain wasn’t so lucky. The future Senator and Republican nominee for US President was in the middle of a bombing mission over North Vietnam in 1967 when his fighter plane was gunned down. He was rescued at Truc Bach Lake and sent to Hoa Lo Prison in Hanoi, which American Prisoners of War (PoWs) sarcastically referred to as the Hanoi Hilton.

McCain walked free, but after nearly six years.

Hoa Lo Prison and the War Remnants Museum in Ho Chi Minh City are reminders of Vietnam’s grim past.

Hell On Earth

The brutal French prison system led Vietnamese prisoners to nickname Hoa Lo Prison as “hell on earth”.

One room, known as the cachot (dungeon), has models of prisoners huddled together with their legs in stocks. The morbidity grows as you walk through to the death row cells, one of which has a haunting model of an emaciated prisoner awaiting his barbaric end by the guillotine, also displayed in a large room.

Some prisoners did manage to escape, through two underground sewers, displayed outside. A caption claims that in March 1945, over 100 escaped.

What remains of Hoa Lo Prison (after part of it was demolished in the 1990s) details the horrors of oppression and torture inflicted by the imperialists, and a floor is dedicated to the heroics of revolutionary fighters.

However, the American section is confined, surprisingly, to just a couple of rooms. The exhibits include the uniforms worn by the captured pilots, their prison clothes, utensils.

However, you could be tricked into thinking that Hilton-level luxuries were available to the PoWs, as you see pictures of them playing outdoor sport, chess, being treated to fancy meals, reading letters from home and singing Christmas carols. The prison claims that the PoWs were “treated humanely”, but it contrasts with multiple accounts, on camera and in memoirs, by inmates like McCain and Everett Alvarez Jr (one of the longest-serving PoWs at Hoa Lo) to name a few, that they were inflicted with grotesque acts of torture, comparable with the French.

Fascinating tales by survivors of how they communicated by tapping on walls in secret get no mention here. In these places, it’s hard to expect balanced accounts of war and struggle, so the propaganda at Hoa Lo is hard to miss.

However, no matter whose side of the fence you are on, the destruction and misery of war is real and inescapable.

An estimated 58,000 Americans died, the Vietnamese casualties on both sides were exponentially higher. Pictures show parts of Hanoi reduced to rubble following America’s B-52 carpet bombings in 1972.

Remains of The Day

The War Remnants Museum takes you head on into the horrors of the Vietnam War in graphic detail. This multi-storey building at the centre of Ho Chi Minh City was inaugurated in 1975 as the ‘Exhibition House for US and Puppet Crimes’. The vast compound displays American tanks, helicopters, fighter planes, Howitzers etc, a treat for defense experts and enthusiasts.

The museum too lacks balanced reporting of the war, but is a very sobering experience for its exhibition of horrific pictures, many of which were recovered from cameras of photographers (133 of them) who perished on duty.

The exhibition Requiem, curated by photographers Tim Page and Horst Faas, is a tribute to these photographers, whose images from the battlefield were a shock to the system, to many Americans in particular, who were kept in the dark about the events in Vietnam.

There are many gut-wrenching images — villagers pleading with the US Marines for mercy; a white soldier holding what remained of a Vietnamese soldier ripped apart by a grenade; young children hiding from their captors in a sewer; mass graves.

The gallery Agent Orange shows haunting images of the after-effects of dioxin and napalm, used by the Americans to destroy crops and foliage. Even today, successive generations of Vietnamese and American soldiers who came into contact with the deadly dioxin are born with deformities and diseases of the worst kind.

This museum portrays the Americans and their allies as the aggressors. A sign shows the findings of the Bertrand Russell Tribunal (1967), which held the US government “guilty of genocide”.

The open air exhibition area recreates parts of the prisoner of war camp at Phu Quoc island, run by the then Saigon government, that detained Viet Cong forces. Captions detail the torture techniques used, and accounts from survivors.

The museum, interestingly, doesn’t trumpet the achievements by the North Vietnamese in suppressing the Americans. Images of victory can be seen in the section Historical Truths, which recaps events like the freedom struggle, the 1954 Dien Bien Phu battle that stunned the French into submission, the Fall of Saigon.

The theme on the ground floor is the fight for peace, with images of anti-war protests around the globe, including Calcutta. Pictures of some American PoWs — described, sarcastically or not, as the “special guests” — are reproduced here as well, for the benefit of visitors who couldn’t make it to Hoa Lo.

Pictures show McCain, Alvarez and others returning to Hoa Lo decades after their release, as goodwill visits, revisiting the past, yet not reopening old wounds. Facts may be debated or put to rest, but by the end of the tour, you can’t help but admire the resilience of the Vietnamese.

Political bridges may have been built, but the scars of war will remain, and that’s what the battle-weary country seeks to do through its war museums — remind, forgive, but not forget.

(The featured image at the top shows the Hoa Lo prison or Maison Centrale which the American POWs nicknamed Hanoi Hilton. Photo: Kanishkaa Balachandran)