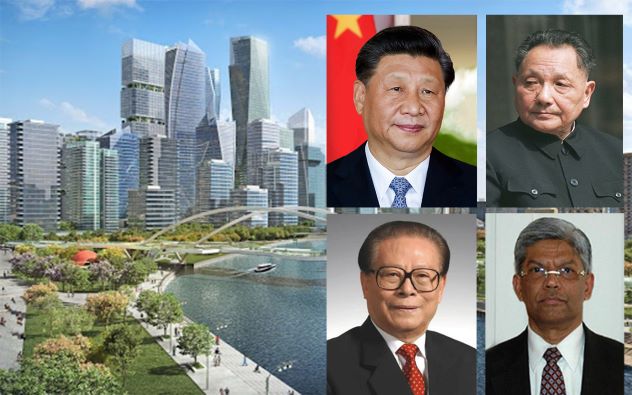

Colombo, April 23 (www.counterpoint.lk): The miracle of “Shenzen” inspired governments globally to find ways and means out of adverse situations that plague countries in terms of their economic performance, especially in the post-second world war era.

Shenzen was well-regarded the world over as the most judicious and prudent way of experimenting with fundamental economic reforms the Chinese leaders wanted to introduce to the country’s economic structure.

It was more of a litmus test of how market reforms such as liberalisation of the economy works within the global economic context.

The man behind the Shenzen success story was Chairman Deng Xiaoping. The story of Shenzen began in May 1980 and spread its wings rapidly across various parts of China, making dramatic and dynamic changes in that country’s economic growth story.

There was a similar success story in respect of economic growth in our own country when President J.R Jayewardene strategically placed Sri Lanka in the global open market by introducing the Greater Colombo Economic Commission (GCEC) through a parliamentary Act even before China embraced the market economy in a more phased out manner. Sri Lanka gradually lost its clout as a pioneering nation in the region to introduce market reforms, perhaps due to unforeseen and unknown reasons and internal political squabbles that led to economic instability.

At one stage former President Jiang Zemin, as a young engineer and a Vice Minister of China, visited Sri Lanka to study the pros and cons of a liberalised economy taking President Jayewardene’s model as a case study before launching the Shenzen in 1980.

Former Foreign Secretary Bernard Goonetilleke who was assigned to Beijing as our ambassador had a personal tete –a- tete with Chairman Jiang Zemin when he presented his credentials some years ago.

Mr Goonetilleke had this interesting story to relate on Chairman Jiang’s visit to Sri Lanka.

I presented credentials as Ambassador of Sri Lanka to the People’s Republic of China to President Jiang Zemin in early 2000 as the successor of Ambassador R.C.A Vandergert. Usually, several newly appointed ambassadors present their credentials to the Head of State at the same time. The usual practice is that the Chinese president makes use of the opportunity to have a short discussion with the newly appointed ambassadors.

When the opportunity came for me to present my credentials to the President, he took approximately forty minutes to engage in a discussion with me which was unusual. The intimate discussion demonstrated not only China’s interest in Sri Lanka as a friendly nation but also his affection towards our country.

The backdrop to the discussion was twofold. The first was the security situation in Sri Lanka resulting from the separatist war which was quite intense around that time. He wanted to get an overall picture of the security situation and how the security forces were managing it, in particular who was responsible for supporting the LTTE. His interest was justifiable on two counts. One was that China was among the few countries that were supporting Sri Lanka against the LTTE, supplying arms, ammunition and heavy artillery weapons to fight the guerailla group. The second was that China itself was facing a similar security situation in the Xinjiang autonomous region which was getting intense at that time.

The second area of discussion related to Sri Lanka’s experience with the open economy introduced by the government of late President J.R. Jayewardene. As you would recall, China itself was moving in the direction of an open market economy and welcoming foreign investments during the latter part of the 1970s. The new administration in Sri Lanka wanted to open up the economy and sought the assistance of the UNDP to get it moving in a new direction. For this, in 1978 the government sought the support of UNDP and through it obtained consulting services from Shannon Free Airport Development Company Ltd. Phase I of the GCEC project started in June 1979 and lasted till April 1980 whereupon phase II started in mid-1982 and lasted till 1983. Phase III of the project started in August 1984.

Around this time young Jiang, with a degree in electrical engineering and having worked as an engineer in several factories, had become Vice Minister of the State Commission on Imports and Exports (1980) and become a member of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party (1982).

During the conversation President Jiang said that in the early 1980s China was looking for a suitable model to open up its economy and sought the help of the UN (I presume it was UNDP) and decided to dispatch a team of experts for a study. For this purpose, they had selected two countries viz. Malaysia, which already had an open economy and Sri Lanka, which was moving from a closed to a free market economy with the establishment of GCEC assisted by the UNDP.

During the discussion, he said that the Chinese team first went to Malaysia and later visited Sri Lanka. He said that the government accorded them with all facilities and the GCEC officials were very cordial and helpful and requested the Chinese team to ask any question they wished to ask. After a successful visit, the Chinese team had returned home.

As an afterthought, President Jiang inquired from me whether I knew who was in the Chinese delegation and who headed it? While I knew of the visit, I was not privy to the details of the visit and I told him so. What followed was a burst of loud laughter and thumping of the chest by President Jiang, loudly saying “I”, meaning that that delegation was led by none other than him.

While I do not recall when this visit had taken place, it would have taken place around 1980 or 1981, in between Phase I and Phase II of the GCEC project. The rise of the Chinese economy commenced with the opening up of foreign trade and investment and the implementation of free-market reforms in 1979 which coincides with the establishment of the GCEC. There was no looking back so far as China was concerned, returning a real annual gross domestic product (GDP) growth averaging 9.5% through 2018, a pace described by the World Bank as “the fastest sustained expansion by a major economy in history”.

Not even President Jayewardene would have thought that the young Vice Minister would become the President of China at a later stage.

President Jayewardene by all means was acting contrary to the assertions of the closed economic concept of Prime Minister Sirimavo Bandaranaike and cracked open the economy to compete with external market forces.

He was aware of the intricacies that would crop up with controversial legislation where the Commission was empowered to amend or suspend certain laws stipulated in a Schedule of the Act.

President Jayewardene was mindful to enact the Greater Colombo Economic Commission (GCEC) Act when the 1972 first republican constitution was still in force and the National State Assembly, which was later replaced and named as the Sri Lanka Parliament under the constitutional reforms introduced by him in September 1978, was in existence.

The GCEC Act came into being in March 1978 under which Sri Lanka’s first Special Economic Zone was established.

Through the1978 Constitution, among other things, the then UNP government in power added an entrenched provision which stipulates that the ‘Sovereignty of the People’ that included the legislative power of the people exercised through Parliament. Article 3 of the 1978 constitution makes the sovereignty of the people inalienable and Parliament in that context is unable to abdicate its power of suspending or amending Acts of Parliament and delegate the legislative power to another institution. Therefore, where the Colombo Port City Economic Commission (CPCEC) Bill is concerned, the government must take a fresh look at some of the provisions which would enable the Commission to exercise legislative power and which may fall outside its ambit. Legal experts are of the view that to make it workable, the government may have to go before the people for approval unless it finds another way out to surmount this difficulty.

With the GCEC Act, President Jayewardene nevertheless circumvented a foreseeable difficult situation by passing it when the 1972 Constitution was in force. A two-thirds majority was sufficient to bring or introduce any reform necessary to make the GCEC workable. In the absence of the referendum clause linked to sovereignty in the constitution, President Jayewardene fulfilled the required tenets of granting the Commission the power to make necessary amendments to the parliamentary Acts specified in the Schedule. However, in the present context the government has to exercise caution in dealing with this specific situation.

The Colombo Port City Economic Commission is the second of its kind that is similar to the GCEC to encourage foreign direct investments to the country in a bid to boost its economic prospects. The main objective of the Colombo Port City Economic Commission (CPCEC) Bill is to showcase Sri Lanka to the entire world as a potential investment destination and an economic hub in the Indian Ocean with incentives. There are many arguments that it will be a separate entity and a pseudo-Chinese colony, but this argument does not hold any water. The definition for a separate state is stipulated in the Montevideo Convention which came into force in December 1933 among Latin American countries and the United States and is now considered a part of International Law. The criteria for statehood according to the Convention are that a state must possess a permanent population, a defined territory, a government, and the capacity to conduct international relations. As far as the Colombo Port City is concerned none of the conditions required to fulfil this have been found.

Minister of Justice Ali Sabry claimed that the Port City is very much a part of the Colombo administrative district but then there are arguments that the Bill should go before the Western Provincial Council for approval. Gamini Marapana, Presidents Counsel, however pooh-phooed this contention when he said that since the PC’s (Provincial Councils) are not in operation the argument does not arise with regard to the Colombo Port City. This is a point that the Supreme Court, the Apex Court looking into the constitutionality of the Bill, will look at.

In the meantime, the government should also take a close look at Clause 7 and Section 4 subsection 2 of the CPCEC Bill which respectively state that:

The Bill provides for the establishment of a Commission consisting of 5 -7 persons appointed at the sole discretion of the President;

The Commission shall, in consultation with the Project Company, and with the concurrence of the President or in any event that the subject of the Colombo Port City is assigned to a Minister, with the concurrence of such Minister, identify any amendments to the Master Plan, if such amendments are considered necessary in the national interest or in the interest of the advancement of the national economy, to ensure through its viability the enhancement of the businesses carried on, in and from the Area of Authority of the Colombo Port City

These apart, the former Governor of the Central Bank Dr Indrajit Coomaraswamy took a closer look at the CPCEC Bill and emphasized the need to compare it with the provisions of the GCEC which had more autonomy in terms of infrastructure, taxation, customs etc.

Dr. Commaraswamy’s observations are as follows.

Several countries have overcome ideological, political or capacity-related constraints to improving their business climate by creating special economic zones/ enclaves. FDI driven export growth has often been the key to accelerate the growth and employment generation trajectory of an economy. This has been the case for countries as large as China or as small as Singapore. Also, for more centrally planned economies such as Vietnam, or more market-oriented ones. Special zones have been a useful mechanism for attracting FDI and promoting exports as they present a more manageable prospect for pushing through policy, structural or institutional reforms which are more difficult on a national scale.

Shannon, in Ireland, provided an initial template for setting up special zones. Sri Lanka was one of the early movers in the developing world when it implemented the Greater Colombo Economic Commission (GCEC) Act.

The GCEC had a great deal of autonomy in terms of infrastructure provision, taxation and customs. It would be good to compare the GCEC Act with the current Colombo Port City Economic Commission (CPCEC) Bill in terms of their respective provisions concerning these matters.

An important dimension of this comparison needs to be how matters related to public finance (both revenue and public expenditure) are handled in terms of Parliamentary oversight. Any resources that have an impact on the Consolidated Fund would normally involve Parliamentary oversight. One would need to examine the constitutionality of avoiding Parliamentary oversight in such circumstances.

In a country where revenue collection is severely challenged (less than 12 per cent of GDP when peers mobilize over 20 per cent), it is questionable whether such generous tax concessions are necessary.

There is a large volume of research which demonstrates that tax concessions are not an important determinant of the location of investment. There are several other more significant considerations. Sri Lanka built up its vaunted social indicators by consistently collecting 20-21 per cent of GDP (please see op-Ed by Professor Mick Moore in Daily FT). Professor Moore also points out that revenue constraints lead to loss of sovereignty as governments are forced to accept external conditions to raise the financing they require.

Careful consideration should be given to the provisions in the Bill relating to the legal and regulatory functions of the Commission and the entities under it. They should be aligned with good practice elsewhere, particularly about the nexus between oversight functions within the zones and outside it.

The Bill should set out the mix of expertise and experience that should be reflected in the composition of the Commission. It should be built into the Bill as much as possible to ensure that the appointments are based on professional merit rather than political favour. One way of doing this is to provide for bodies such as the Charted Accountants of Sri Lanka, Bar Association of Sri Lanka, Association of Professional Bankers to recommend (even nominate) representatives for the Commission. This may not be perfect, but it is better than leaving it to individual politicians.

Entities such as the Central Bank of Sri Lanka, Attorney General’s Department, Securities and Exchange Commission and Financial Intelligence Unit should have senior ex-officio membership of the Commission or key entities under it.

All provisions of the proposed Act should be carefully screened to ensure that they do not discriminate unduly against the rest of the economy.

I also should point out that taxation serves to transfer some of the benefits accruing from the Colombo Port City to the population at large. This is important given that tax collections would have assisted in financing the infrastructure and educating/ training workers for the CPC.

A recent Price Waterhouse Coopers report states that the Sri Lankan economy stands to gain from the proposed Colombo Port City. According to extracts from the study:

At present, Sri Lanka receives around USD 1.bn to USD1.5bn on FDI annually. Hence the expected flow of FDI would be sizable and it is expected that Sri Lanka will be well-positioned for attracting FDI due to Port City Development. Moreover, it is expected that there will be a spillover effect as well where the Port City may encourage FDI flows outside the project. Taken together, the Port City should be a key driver in attracting FDI in future Sri Lanka.

Government revenue will be derived through several channels during the development of Port City. At the land reclamation and common infrastructure development stage, GoSL may incur some costs for providing certain infrastructure facilities to the outer border of the Port City namely electricity, water, road access etc.

Some concessions and exemptions given on import duty may have a negative impact on government revenue (in terms of loss of royalty payments for sands, import of material etc).

Besides, in each operational year, the government could receive USD 800 million worth of revenue from income taxes, import duties, license fees etc. Taken together, the Port City will be a good source of revenue generation for the government and would certainly support the GoSL in increasing its expenditure on development and welfare activities elsewhere, along with reducing the dependency on borrowing. However, it should be noted that the estimates were based on the prevailing/proposed tax rates and any exemptions or concessions provided for the operators within Port City may lead to a reduction in tax revenue.

The economic impact assessment undertaken which captures both direct and indirect effect clearly indicates that the Port City would have a significant impact on the national economy in terms of employment generation, attracting FDIs, GDP contribution, BOP (Balance of Payment) and government revenue when it progresses as envisaged.

The Port City could be classified as a strategic investment project and a potential source and driver of economic growth and development for Sri Lanka. Such investment projects elsewhere in the world have historically played a significant role in transforming developing economies into more advanced ones.

One of the key determining factors in achieving the expected result would be the pace of the city development process and the enablement of its smooth functioning. Delays in construction, as well as the red tapes to functioning, could significantly lower the economic potential. In this context, it would be beneficial to have a clearly defined regulatory policy framework for Port City, as this would support the achievement of the aforementioned economic targets. It is important to highlight that in addition to the impact on economic growth, any negative developments and barriers could affect the attraction of FDI’s to the Port City project and other investment projects in Sri Lanka.

Port City in short gives an explicit picture of how Sri Lanka could develop its economy to go forward in the global economic melee and stand as a steadfast economy in the developing world.

END