By P.K.Balachandran/Daily Mirror-Colombo Diary

Colombo, May 28: In contrast to iconic Tamil Nadu leaders like K.Kamaraj or M.G.Ramachandran (MGR), who were invariably portrayed glowingly, Muthuvel Karunanidhi, leader of the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) and many times Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu, was dogged by negative portrayals.

To his adoring followers, he was the quintessential Tamil icon and a relentless crusader for the Tamils’ rights and a promoter of social justice. But to his opponents, he had institutionalized corruption and was a radical Tamil nationalist who, at times, betrayed secessionist ideas.

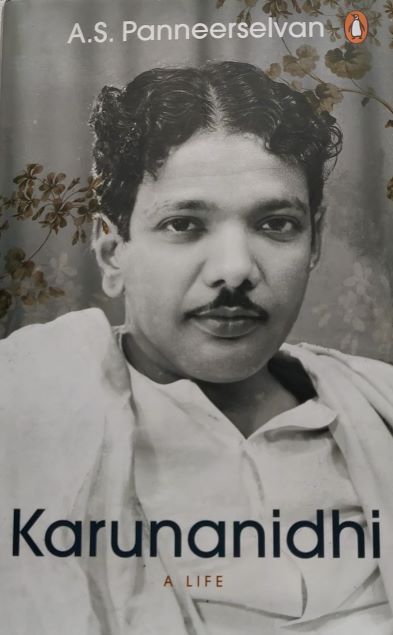

A.S.Panneerselvan’s just released biography of Karunanidhi entitled: “Karunanidhi: A Life” (Penguin/Viking 2021), shows the Tamil leader in a very favorable light. Rich in detail, it cites context after context in which Karunanidhi was deliberately wronged by interested parties. In the chapter on the Sri Lankan Tamil issue, Paneerselvam argues that Kaunanidhi’s policy was “refined and nuanced” and “statesman-like”.

His stance was aimed to bringing about a negotiated settlement sans intimidation of any kind, but the Indian and Sri Lankan Establishments and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), believed in the dictum: “either you are with us or you are against us.” Thus, Karunanidhi’s sane counsel was routinely disregarded resulting in a destructive war and the destitution of Tamils.

Two-Pronged Approach

Panneerselavan says that Karunanidhi advocated a two-pronged negotiating policy: He wanted the Tamil groups to have a “maximalist” goal at one level, and a “minimalist” one at another level. As trade unions do: ask for more to get what is possible. For Karunanidhi an independent Tamil Eelam was the maximalist demand but it was unattainable. Devolution of power under “13th.Amendment Plus” was the attainable “minimalist” demand. However, Karunanidhi fought a losing battle on this issue because all parties involved were wedded to maximalist notions, Panneerselvan says.

“Sole Representative” Status

The Tamil Nadu leader was by no means a blind supporter of the LTTE at any point of time, Panneerselvan submits. Karunanidhi opposed the inter-militant group clashes in the late 1980s which stemmed from the LTTE’s bid to be the “sole representative of the Tamils.” Karunanidhi felt that the LTTE’s fixation with being the sole representative “actually robbed the group of its perfectly legitimate claim of being one of the major representatives of the Tamils.”

He warned that the fratricidal warfare “would not lead to liberation but to a situation where we will lose sight of who is our enemy, and what is the purpose of our struggle.” However, his inclusive approach did not endear him either to the LTTE or its influential Diaspora supporters. The biographer complains that the Jain Commission, which went into the larger conspiracy behind the assassination of Rajiv Gandhi, “conveniently blacked out” Karunanidhi’s restrained and qualified relations with the LTTE. The panel blamed his government for giving the LTTE a free run of Tamil Nadu which preceded Rajiv’s assassination, but ignored the way others mollycoddled the LTTE. Karunanidhi wondered why the Jain Commission was silent about Rajiv Gandhi’s two meetings with LTTE emissaries in 1991 and why few talked about the arms training given to the LTTE by the Indian government.

The fact that the Indian and Lankan governments were recognizing the LTTE as the “sole representatives of the Tamils” was brushed under the carpet. At the SAARC summit in 1986, President J.R.Jayewardene had acknowledged LTTE leader Prabhakaran’s primacy and wanted to talk to him, and India went along. After the 1987 India-Sri Lanka Accord, Indian and Lankan governments gave a preponderance of seats to the LTTE in the Interim Administrative Council for the united North-Eastern Province. During R.Premadasa’s Presidency, Colombo held talks only with the LTTE. And in 1989, Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi himself asked Karunandhi to talk to the LTTE. And yet, Karunanidhi was routinely accused of being a puppet of the LTTE.

Relations with LTTE

Panneerselvan says that relations between Karunanidhi and the LTTE were not always cordial. In 1986, the LTTE refused to accept the money he had collected for the Tamil Eelam cause. The LTTE rejected the offer for fear of alienating MGR, who not only gave money to the LTTE but funded only the LTTE. Karunanidhi, on the other hand, wanted to distribute the money among all groups, including the moderate Tamil United Liberation Front (TULF). He viewed the expulsion of Muslims from the North by the LTTE in 1990 as “ethnic cleansing.”

Foreign Mediation

Keen on a peaceful settlement, Karunanidhi supported the 1994-96 Liam Fox and the 2002-04 Norwegian mediatory initiatives. He convinced Prime Minister A.B.Vajpayee to give the Norwegians a chance so long as they did not affect India’s geo-political interests.

Opposition to IPKF

In 1990, Karunanidhi (with the assistance of cabinet minister George Fernandes) convinced Indian Prime Minister V.P. Singh to withdraw the Indian Peace Keeping Force (IPKF) from Sri Lanka. He was resolutely against the induction of troops to keep the peace anywhere in any country. “Peace-keeping is not a military task, and whenever the military has been deployed, the civilian government is rarely able to get them back to the barracks. On the other hand, we are forced to come up with new acts to defend ourselves, when there is little progress on the ground,” Karunanidhi said. He was referring to the Indian Armed Forces Special Powers Act.

“Karunanidhi felt that the LTTE’s fixation with being the sole representative “actually robbed the group of its perfectly legitimate claim of being one of the major representatives of the Tamils”

He warned that if the IPKF was not brought back, it would have stayed there forever. “I am grateful to Prime Minister V.P.Singh and the External Affairs Minister I.K.Gujral for agreeing to my suggestion to bring back the Army without subjecting it to further bloodletting. In peace-building we need the language of fluidity rather than a language of aggression, which flows from the presence of armed forces,” Karunanidhi said.

Disturbing Denouement

He was deeply saddened by the denouement of the armed struggle in Sri Lanka. In his last discussion with Panneerselvan on the Sri Lankan question in April 2011, Karunanidhi said that the Lankan Tamils have paid a huge price.

He added that his concern was “to address the question rather than win the appreciation of some diaspora LTTE supporter who forms his opinion based on, not the second – but tenth hand sources.”

What Is Missing

What does not come through in the book is the fact that, like other Tamil Nadu politicians, Karunanidhi was deftly using the Lankan Tamil issue to capture and keep power. He played to the Tamil nationalist gallery to the hilt when it could pay political dividends as in the 1989 State Assembly elections. From 1989 to January 1991, (when his government was sacked), Karunanidhi brazenly gave the LTTE a free run of Tamil Nadu. The result was the massacre of the leadership of the Eelam Peoples’ Revolutionay Liberation Front (EPRLF) including Supremo K.Pathmanabha in Chennai in 1990. The escape of the assassins was facilitated by the State police, said M.M.Rajendran, Karunanidhi’s Chief Secretary.

Karunanidhi carried out a sustained vilification campaign against the IPKF throughout its tenure in the island from 1987 to 1990, calling it the “Indian Peace Killing Force” indulging in mass killings of Tamils. Playing to the Tamil gallery both at home and abroad, he boycotted the official function to receive returning IPKF troops at the Chennai harbour. In 2009, he went on a fast to stop the war in Sri Lanka, but being pragmatic, he ended it at the instance of his political ally, the Congress government in Delhi.

No doubt Karunanidhi had a pro-Tamil ideology which he implemented substantially, but he was also flexible and pragmatic with an eye on political realities.

END