By Sugeeswara Senadhira/Daily FT

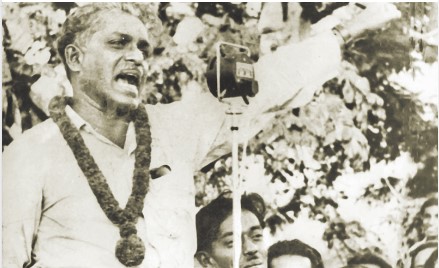

Colombo. March 28: The radical leftist movements today could learn lessons from the legacy left by the Father of Socialism in Sri Lanka, Philip Gunawardena, whose genuine desire was to serve the downtrodden people using whatever means available. Philip was a pragmatic leader who instinctively understood the hopes and aspirations of the people, a man close to the heartbeat of the nation.

His courage was legendary and it earned him the sobriquet ‘Lion of Boralugoda’. Although Philip was known as the ‘Father of Marxism in Ceylon’ in his radical days when he launched the Lanka Sama Samaja Party (LSSP) together with N.M. Perera, Colvin R. de Silva and other pioneers of the Left movement, he realised soon that the foreign doctrine would have to be transformed to meet the people’s aspirations. Hence, he launched the new vision of ‘National Socialism’ loosely translated as ‘Jathika Samajavadaya’.

As a youth, he followed a radical revolutionary path that made him work in close collaboration with socialist leaders of many countries including in the United Kingdom, United States, Spain and India. In New York he joined the radical group headed by José Vasconcelos Calderón, called the “cultural caudillo” of the Mexican Revolution. Calderón was an important Mexican writer, philosopher, and politician. He was one of the most influential and controversial personalities in the development of modern Mexico.

Philip’s daughter Lakmini Gunawardena told this writer some years ago that the niece of the Mexican revolutionist Calderón came to Sri Lanka. “My father met her and worked with other people who joined freedom struggles in Spain,” she said.

In London, Philip was closely associated with fellow socialists from India such as Jayaprakash Narayan, Jawaharlal Nehru and Krishna Menon and Jomo Kenyatta of Kenya. He assisted Spanish revolutionaries and helped them to smuggle revolutionary documents to the Pyrenees range of mountains by avoiding the border checkpoints between Spain and France.

After returning to Sri Lanka to launch the LSSP and its famous Suriyamal Campaign and social work during the Malaria epidemic, he continued to maintain close contacts with the Indian socialist leaders, which became useful when he crossed over to India with colleagues NM, Colvin and others after breaking out of Batticaloa Jail where he was imprisoned by the colonial rulers. He joined the Indian freedom struggle while hiding in India until the colonial police in India captured him as well as his wife Kusuma and imprisoned them in Bombay Jail.

As a Trotskyite, Philip focused his vision of Trotskyism blending it with nationalism, rather than totally devoting his vision to Marxist theories. The new-found ‘Social Nationalism’ could easily blend with S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike’s middle path and the new pancha maha balawegaya of the Buddhist clergy, indigenous physicians, teachers, peasants and labourers brought the new-found Mahajana Eksath Peramuna (MEP) to power in 1956.

After parting ways with Bandaranaike a few months before the tragic death of Bandaranaike, Philip decided not to revive his Revolutionary Lanka Sama Samaja Party (VLSSP). Instead he became the leader of MEP, a party which followed the left of the middle path.

As eminent administrator and academic-turned politician Dr. Sarath Amunugama said, on Socialism itself Philip had a different perspective from the red-shirted comrade shouting himself hoarse on May Day: “You talk of Socialism. You cannot socialise poverty. You can only socialise plenty. And if people cannot work, if they cannot produce, you cannot have Socialism.” This was probably an admonition to the government of the day which was claiming to be Socialist.

Professor A.V.D.S. Indraratne, the prominent economist, taking a look at Philip’s achievements, stated that he brought Marxism to the rural peasants through his Jathika Samajavadaya.

Today, radical socialist parties are faced with an identity crisis. They are highly perturbed by the non-acceptance by the vast majority of the people, though they are very popular with the youth segment of society. They can learn a lesson from left-wing nationalism or leftist nationalism adopted by Philip. During the colonial era he used it as a policy of anti-imperialism and national liberation movement. In independent Sri Lanka his policy was based upon national self-determination, popular sovereignty, national self-interest, and left-wing political positions such as social equality.

This is quite evident from his speeches. Speaking in the course of the Budget debate on October 11, 1960, Philip, then a member of the Opposition, said, “In our country with its accent on political illiteracy, there is the danger of a class struggle between the ignorant and the educated. The modern world is a complex world; its technological problems need a cultivated understanding. The fact that new ideas and learning mostly come to our country through a foreign language creates new barriers between the educated elite and the unsophisticated people. The new ideas and learning do not naturally seep down, fail to become a part of the heritage and the consciousness of the people and they remain a monopoly of the new Nationalisation of modern knowledge which is the sine qua non of effective democracy and Socialism in our country.”

The relevance of Philip’s vision can be encapsulated in another segment of his speech. “The growing divorce between words and their meaning is a major tragedy of our times. Socialism, Democracy, Peace, and Freedom are used in a manner that makes them not only meaningless but topsy-turvy. The fluidity in the meaning of words creates a crisis in communication. Words instead of clarifying and crystallising thoughts confuse it. Today counterfeiters have seized the temple of Saraswathi. As false coins bring about the breakdown of an economy and society, counterfeiters in language destroy popular confidence. Dull indifference is the only response when not the goblet alone but the grapes are without wine.”

END