By Ahmed Faruqui/Daily Times

In his memoirs, “The Betrayal of East Pakistan”, published almost 30 years after his surrender in Dhaka on 16 December, 1971, Lt-Gen A.A.K. Niazi sought to respond to critics who had argued that his decision to surrender without a fight for Dhaka was ill advised.

He claimed that he “had vast experience of commanding troops. The troops under my command were probably the best in the world.” He says that General Abdul Hamid Khan, the Chief of Staff under General Yahya Khan, who was also the president, had called him “the highest decorated officer of our Army, and one of our best field commanders.”

However, the facts are that he had no experience of high command, least of all a command at the theatre level.

Niazi considered himself the most decorated officer in the Pakistan army prior to his appointment in Dhaka. His decorations included the Hilal-e-Jurat, the highest medal for gallantry that is awarded in Pakistan to living soldiers, earned during the 1965 war. Yet Lt-Gen Gul Hassan, the Chief of the General Staff during the war, stated in his memoirs that Niazi was one of the weaker divisional commanders prior to his promotion to Lt.-Gen. and his appointment to Eastern Command. He says that Niazi’s professional “ceiling was no more than that of a company commander”, which means he was at best, fit enough for the rank of a captain.

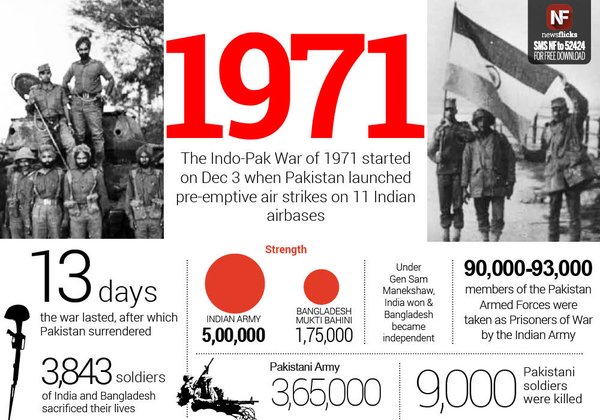

Once the PAF attacked Indian air bases on 3 December 1971, thus declaring an outright war, Niazi did not venture out of Dhaka. Of course, neither Generals Yahya nor Hamid had ventured into East Pakistan since they launched the ill-conceived Operation Searchlight on 25 March.

With the fall of Dhaka being imminent, Niazi called a press conference and boasted that Dhaka would have to fall over his dead body. To eliminate any doubt, he puffed up his chest, and stated that Dhaka would not fall until the Indians drove a tank over his chest. In a few days, he came to realize that only 5,000 of the 93,000 troops and supporting irregulars under his command were available for the defense of Dhaka. As noted by Captain Siddiq Salik, his press relations officer during the war, and author of “Witness to Surrender,” the army had been deployed in “penny packets” all around the border with India to prevent India from seizing territory and setting up a puppet state.

When he saw the end coming, Niazi requested the GHQ in Rawalpindi to arrange air strikes against Indian forces around East Pakistan, and to send in airborne reinforcements. Gul Hassan comments: “Even a second lieutenant would have known that … Pakistan did not have the capability for staging such operations.” Captain Salik reported that Niazi optimistically thought that the paratroopers who were being dropped around Dhaka in the final stages of the war were either Americans from the South or the Chinese from the North.

Looking at his record during the war, it is clear that Niazi displayed a consistent pattern of blindly following orders coming from GHQ. Three such orders led to disaster:

The first order was to accept the command of the Eastern Garrison. He knew that he “had been given a rudderless ship with a broken mast to take across the stormy seas, with no lighthouse for me in any direction.” He would be operating in a theater that had no possibility of getting reinforcements from the west, in a hostile countryside swarming with rebel forces.

The second order was to not take the war into India, even though he had planned to “capture Agartala and a big chunk of Assam (to the east of East Pakistan), and develop multiple thrusts into Indian Bengal (to the west of East Pakistan).

“We would cripple the economy of Calcutta by blowing up bridges and sinking boats and ships in the Hoogly River and create panic among the civilians,” he said.

But this proposal was rejected by General Hamid who said that the Pakistan government was “not prepared to fight an open war with India…You will neither enter Indian territory nor send raiding parties into India, and you will not fire into Indian territory either.”

And the third order was to surrender the Eastern garrison to India, “to save West Pakistan, our base, from disintegration and Western Garrison from further repulses.”

In an ironic reversal of Pakistan’s strategic doctrine that “the defense of the East lay in the West,” the survival of West Pakistan had now become contingent on the surrender of East Pakistan.

Niazi rightfully contends that Yahya disappeared from East Pakistan after launching Operation Searchlight. To make matters worse, when asked about the situation in East Pakistan, Yahya would say, “All I can do about East Pakistan is pray.”

During the war, General Hamid visited the troops in the East just twice. Lt-Gen Gul Hassan would not answer Niazi’s phone calls. Sadly, the top brass of the Pakistan army had abandoned their “most decorated officer” to his own devices.

Niazi does not accept any blame for the loss of East Pakistan. He says he challenged the Pakistan Army to court-martial him, but they refused. Of course, it is likely that such proceedings would have implicated not only the top army brass but also Niazi afortiori. This was borne out by the judgments contained in the Hamoodur Rahman War Commission. Referring to Niazi, the Commission found that:

[E]very Commander must be presumed to possess the caliber and quality, appurtenant to his rank, and he must perforce bear full responsibility for all the acts of omission and commission, leading to his defeat in war, which are clearly attributable to culpable negligence on his part to take the right action at the right time. He would also be liable to be punished if he shows a lack of will to fight and surrenders to the enemy at a juncture when he still had the resources and the capability to put up resistance. Such an act would appear to fall clearly under clause (a) of section 24 of the Pakistan Army Act.

In his History of the Pakistan Army, Col. Brian Cloughley noted: “Yahya bore overall responsibility for what befell his country; but General Niazi was the commander who lost the war in the East… He was just not suited to high command.”

According to Lt-Gen Gul Hasan, there was no reason why the Eastern Garrison of the Pakistani army would in mere 13 days since it had more than 45,000 soldiers in fighting condition but “with Niazi at the helm, they had no chance.”

Of course that begs the question of who put Niazi there. The most strategic command in the army was turned over to a “hastily promoted” General. The list of culprits begins with Generals Yahya and Hamid but neither can it exclude Lt-Gen Gul Hasan, who was later promoted after the war to Army Chief of Staff.

(The writer is a defense analyst and economist. He has authored Rethinking the National Security of Pakistan (Ashgate Publishing, 2003)