By, Sautik Biswas/BBC

In 2014, while sitting in an office in London’s Mile End historian Kim Wagner received an email from a couple who said that they owned a skull.

Dr Wagner, who teaches imperial history at Queen Mary University of London, says the couple told him they did not feel comfortable with the “thing” in their house, and did not know what to do with it.

The lower jaw of the skull was missing, the few remaining teeth were loose, and it had the “sepia hue of old age”.

But what was remarkable was a detailed handwritten note in a neatly folded slip of paper inserted in an eye socket. The note told the brief story of the skull:

Skull of Havildar “Alum Bheg,” 46th Regt. Bengal N. Infantry who was blown away from a gun, amongst several others of his Regt. He was a principal leader in the mutiny of 1857 & of a most ruffianly disposition. He took possession (at the head of a small party) of the road leading to the fort, to which place all the Europeans were hurrying for safety. His party surprised and killed Dr. Graham shooting him in his buggy by the side of his daughter. His next victim was the Rev. Mr. Hunter, a missionary, who was flying with his wife and daughters in the same direction. He murdered Mr Hunter, and his wife and daughters after being brutally treated were butchered by the road side.

Alum Bheg was about 32 years of age; 5 feet 7 ½ inches high and by no means an ill looking native.

The skull was brought home by Captain (AR) Costello (late Capt. 7th Drag. Guards), who was on duty when Alum Bheg was executed.

What was clear from the note was that the skull was of a rebel Indian soldier called Alum Bheg, who belonged to the Bengal Regiment and who was executed in 1858 by being blown from the mouth of a cannon in Sialkot (a town in Punjab province located in present-day Pakistan); and that a man who witnessed the execution brought the skull to England. The note is silent on why Bheg committed the alleged murders.

Native Hindu and Muslim soldiers, also known as sepoys, rebelled against the British East India Company in 1857 over fears that gun cartridges were greased with animal fat forbidden by their religions. The British ruled India for 200 years until the country’s independence in 1947.

The couple in Essex had trawled the internet and failed to find anything about Bheg. They contacted Dr Wagner after they found his name as a historian who had authored a book on the Indian uprising, often referred to as the first war of independence.

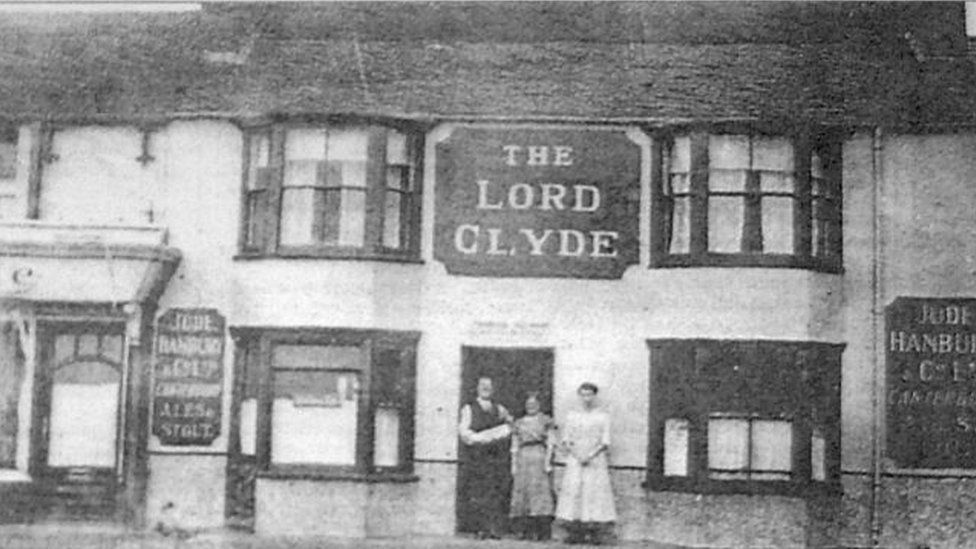

On a wet November day, which was also his birthday, Dr Wagner met the couple. They told him that they had inherited the skull after one of their relatives took over a pub in Kent called The Lord Clyde in 1963, and found the skull stored under some old crates and boxes in a small room in the back of the building.

Grisly Trophy

Nobody quite knows how the skull ended up in the pub. The local media had excitedly reported on the “nerve-shattering discovery” in 1963 and carried pictures of the new pub owners “proudly posing with the grisly trophy” before it was put up on display at the pub. When the owners died, it was finally passed on to their relatives who simply hid it away.

“And so it was. I found myself standing in a small train station in Essex with a human skull in my bag. Not just any other skull but one directly related to a part of history that I write about and that I teach my students every year,” says Dr Wagner.

What was very clear, he says, is that it was a “trophy skull, irrevocably linked to a narrative of violence”.

But first Dr Wagner had to confirm that the skull matched the history outlined in the note, written by an unknown person. At London’s Natural History Museum, an expert examined it and suggested that it dated back to the mid-19th Century; and that it definitely belonged to a male of Asian ancestry, who was possibly in his mid-30s.

There was no sign of violence, said the expert, which is not unusual in the case of execution by cannon, where the torso takes the full impact of the blast. The skull also bore cut marks from a tool, suggesting that the head was de-fleshed by being boiled or being left exposed to insects.

Dr Wagner says he did not believe immediately that it would be possible to find out very much more about Bheg.

Individual soldiers rarely left any traces in the colonial archives, with the possible exception of someone like Mangal Pandey, who fired the first shot at a British officer on 29 March 1857 on the outskirts of Kolkata and stirred up a wave of rebellion in India against the colonial power.

Bheg’s name was not mentioned in any of the documents, reports, letters, memoirs and trial records from the period in the archives and libraries in India and UK. There were also no descendants demanding the return of the skull.

But there were a were a few helpful discoveries.

Piecing the Story Together

Dr Wagner found the letters of Bheg’s alleged victims to their families. What proved crucial, he says, in piecing the story together were the letters and memoirs of an American missionary, Andrew Gordon, who lived in Sialkot during and after the uprising. He knew both Dr Graham and the Hunters – Bheg’s victims – personally and he had attended the soldier’s execution.

There was also a revealing report in the illustrated newspaper, The Sphere, in 1911 on a grisly exhibit in a museum in Whitehall:

The ghastly memento of the Indian Mutiny has, we are informed, just been placed in the museum of the Royal United Service Institution at Whitehall. It is a skull of a sepoy of the 49th Regiment of Bengal Infantry who was blown from the guns in 1858 with eighteen others. The skull has been converted into a cigar box as we see.

The newspaper said that “while we may be able to understand all the savagery of the terrible time – the cruelty of the natives and the cruel retribution that followed – is it not an outrage that a memento of our retribution, which in these days would not be tolerated for a moment, should be placed on exhibition in a great public institution?”

Battling a famine of evidence, Dr Wagner began researching Bheg. He worked in the archives in London and Delhi, and traveled to Sialkot to locate the forgotten battlefield of the four-day Trimmu Ghat clash in July 1857 – during which the Sialkot rebels, including Bheg, were intercepted and defeated by General John Nicholson. The General was mortally wounded two months later leading the assault to recapture Delhi from the mutineers. .

He relied on letters, petitions, proclamations and statements by rebels after the outbreak of the uprising, went through 19th Century newspaper databases and scanned books.

“It was only after I spent some time researching the story, in the UK and in India, that I managed to piece a historical narrative together and realized that there was a bigger story to tell,” he told me.

‘Detective novel’

The result is Wagner’s new book, The Skull of Alum Bheg, a vivid page-turner on life and death in British India during the largest anti-colonial revolt of the 19th Century. Yasmin Khan, associate professor of history at the University of Oxford, says the book “reads like a detective novel and yet is also an important contribution to understanding British rule and the extent of colonial violence”.

Dr Wagner writes that his book sets out to “restore some of the humanity and dignity that has been denied to Alum Bheg by telling the story of his life and death during one of the most dramatic episodes in the history of British India”.

“I hope I have prepared the ground for Alum Bheg to finally find some peace, some 160 years late.”

In Dr Wagner’s telling, Alum Bheg – properly transliterated as Alim Beg – was a Sunni Muslim from northern India. The Bengal Regiment was raised in Cawnpore (now Kanpur) in today’s Uttar Pradesh state, and it is likely that Bheg hailed from the region. Muslims made up around 20% of the largely Hindu regiments.

Bheg was responsible for a small detachment of soldiers, and had a grueling routine, guarding the camp, carrying letters and working as a peon for higher officials of the regiment. After the revolt in July 1857, he appeared to have evaded the British troops until his capture and execution nearly a year later.

Resting place

Captain Costello, who was described as being present at the execution in the note, was established as Robert George Costello. Dr Wagner believes he is the man who brought the skull back to Britain. He was born in Ireland and sent to India in 1857, and retired from his commission 10 months later, boarded a steamer from India in October 1858, and reached Southampton a little more than a month later.

“The final aim of my research is to prepare for Bheg to be repatriated to India, if at all possible,” Dr Wagner says.

He says there have been no claims to the skull, but he’s in touch with Indian institutions and the British High Commission in India is also involved in the initial discussions.

“I am very keen for Alum Bheg’s repatriation not to be politicized, and for the skull not to end up in a glass-case in a museum or simply be forgotten in a box somewhere,” says Dr Wagner.

“My hope is for Alum Bheg to be repatriated and buried in a respectful manner in the near future.”

A fitting place to bury Bheg, he believes, would be on the island on the Ravi river, where the sepoy and his fellow soldiers had taken refuge after surviving the first day of the battle and which today marks the border between India and Pakistan.

“Ultimately, that is not for me to decide, but whatever happens, the final chapter of Alum Bheg’s story has yet to be written.”

END