By, Chitra Ramaswamy/The Guardian

Before there was Isis, the extremist militant group responsible for the most brutal terrorist attacks and killings of recent years, there was Isis: an 11-year-old girl in Kent whose mother named her after the ancient Egyptian goddess of fertility, magic and motherhood.

“I was really proud of it,” Isis Hales says. And now? “I just …” she trails off and her mother, Lucy, steps in. “You wanted to change your name, didn’t you?” “Yeah,” Isis replies quietly. “That was about four months ago.”

As Isis has come to control vast swathes of territory in Syria and Iraq, and claimed responsibility for terrorist attacks all over the world, Isis has been bullied more at school. In a few years her name has gone from being “lovely and unusual” to a byword for violent extremism and murder.

“In year six,” as she puts it, “it really hit me in the face.” It may be one of the less significant and visible consequences of the rise of the terrorist group, and specifically the increase in Islamic State being referred to as Isis, but for women and girls who find themselves sharing a name with a hardline jihadist network, life can be a nightmare.

“It’s not every single day,” Isis insists, “but it doesn’t seem to be stopping. When I was leaving primary school and we were all signing T-shirts to say goodbye, someone wrote ‘ISIS’ on mine. People call me a terrorist and ask me where’s my machine gun. It’s really difficult. I don’t want to change my name any more but I want to do something about it.”

Lucy named her daughter Isis for a specific reason. “I didn’t think I could have children,” she explains. “We tried for several years. I had IVF but got poorly, and then just before I started the treatment again I fell pregnant naturally. Isis is the Egyptian god of love and fertility and that’s how she got her name. She was and is very special.”

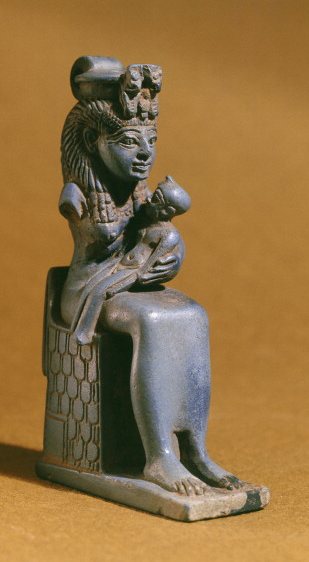

The wife of Osiris and mother of Horus, god of the sun, Isis was one of the most important goddesses in ancient Egypt. Depicted as a woman with outstretched, winged arms and an empty throne on her headdress, she was revered as the people’s goddess, teaching wisdom, agriculture and medicine. More than any other goddess, Isis represents the complete female. She has been worshipped for centuries; throughout ancient Egypt and the Roman Empire, and today, by pagans all over the world as a potent symbol of feminism.

“My mum wanted to choose something unusual,” says Isis Blackwell, who was named after the goddess in the 80s. “When I was younger she told me the story of Isis and Osiris and I have lots of Isis-related art and statues. I loved my name. It was a good conversation starter and it made me feel a bit different.”

The first time she heard her name associated with Islamic State was in 2012 when she was sent an article about the jihadist group on Facebook with the comment: “I see you’ve been up to no good in the Middle East.” “It was a joke, I suppose,” she says uneasily. “Disheartening, but I didn’t think it would last.”

Unfortunately, it got worse. At work, where she wore a name badge, people started to comment on how unfortunate her name was and ask why she hadn’t considered changed it. Earlier this year she was temporarily banned from Facebook.

“I tried to log in and got a message saying you can’t have offensive words in your name,” she tells me. “My mum was probably the most upset about it. She would never have wanted to choose an offensive name for me.”

Ironically, considering Isis’s current association, the goddess Isis influenced both Muslim and Christian religions. The annual flooding of the Nile is still celebrated by Egyptian Muslims as a remembrance of Isis’s grief at the death of Osiris causing the river to overflow.

In the fourth century, Christian worshippers of Isis founded the first Madonna cults in her memory and some called themselves Pastophori, meaning shepherds of Isis. It is thought that ancient images of Isis nursing her infant son are the inspiration for the Madonna and child portraits depicted in centuries of religious art and iconography.

Isis pops up in popular culture too, if you search “Isis name” on Google or visit Wikipedia’s “Isis disambiguation” page. Isis is the name of a strange and lovely 1975 Bob Dylan ballad thought to be about the break-up with his then wife, Sara, that opens with, “I married Isis on the fifth day of May …”.

Isis is a 17th.Century French opera based on Ovid’s Metamorphoses, a character in Stargate and Battleship Galactica. The Isis river is a section of the Thames running through Oxford, giving its name to the university boat club’s reserve rowing team and to the student magazine. Victorians believed the Thames was correctly named the River Isis and some historians insist the name is part of Tamesis, the Latin name for the Thames. There are still Ordnance Survey maps that label the Thames as “River Thames or Isis”.

Until 2014 Isis was a relatively popular name, particularly in the US, where it had ranked in the top thousand baby names for girls for 15 years. One year later, it dropped off the list completely. Now even companies called Isis are changing their name, from a language school in Oxford to the World Meteorological Organization replacing Hurricane Isis with Ivette.

At the same time the discussion of what to call the terror organization continues. Islamic State, which is how the group has referred to itself since 2014, has fallen out of favor because it wrongly presumes it is both Islamic and a legitimate state, and the BBC now refers to it as “the so-called Islamic State”.

UN and US officials generally use Isil, an acronym of the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant. When urging MPs to back bombing in Syria in 2015, David Cameronpledged that he would use Daesh, the Arabic acronym employed in the Middle East that the terrorist group reportedly professes to hate so much it threatened to cut out the tongues of anyone who uses it in public. Much of the media, including The Guardian, continues to use Isis.

“Which means that whenever I say my name, terrorism becomes the topic of conversation,” explains Isis Martinez, a 40-year-old woman based in Miami whose mother was also called Isis after the Egyptian goddess. In 2014 Martinez started a petition urging the media to stop using her name to describe the terrorist group. It gained more than 65,000 signatures but Martinez tells me life remains difficult and she now goes by a different name at work.

“I would rather not have to talk about terrorism all day, every day,” she tells me. “With family and friends I’m still Isis but at work I’ve had to surrender to it. I would rather be happy than right. I can’t fight the world.”

For all the women I speak to called Isis, the solution is for the media to stop using the acronym as if it were a name.

“I try and ignore it,” Isis Hales says when I ask her how she responds to bullying. “Or I say, ‘You know I’m not named after a terrorist, so why are you doing this?’ I just don’t understand it. I wouldn’t do it to them.”

“Isis is going to secondary school [this year],” her mother adds, “and we are braced for pupils to say things like, ‘Are you a terrorist?’ It’s inevitable.” I ask Isis if there is anything else she would like to add. “Please,” she replies without hesitation. “Just stop using Isis.”

Chitra Ramaswamy is a freelance journalist based in Edinburgh. She is the author of Expecting: The Inner Life of Pregnancy.