By P.K.Balachandran

Colombo, August 29: If the Indian moon probe “Chandrayaan 3” was an unqualified success, it was due not only to the scientists who toiled on the project resolutely against odds but also due to Jawaharlal Nehru, the man who built, brick by brick as it were, India’s scientific and technical infrastructure from the day the country became independent.

In his 17-year stint as Prime Minister from 1947 to 1964, Nehru gave India a “national” policy on science and built research and educational institutions in a bid to create a “scientific temper” to guide India in all its endeavours, whether scientific, economic or social.

This is remarkable, in as much as most of Nehru’s colleagues in the freedom movement had no clear blueprint for a free India. Some like Mahatma Gandhi wanted India to return to its rural roots with village industries replacing the “ugly and exploitative” urban factories. Others wanted India to revive its glorious Hindu past. Most just wanted the British to go.

Even as he was Gandhi’s closest lieutenant in the freedom struggle, Nehru had a radically different notion of a free India. He advocated Soviet-style industrialization, application of modern science and technology and the development of a “scientific temper” which he passionately believed, was the panacea for India’s economic and social ills.

In an article in The Statesman in 2019, Praveen Davar recalls that in 1937, ten years before independence, Nehru told the National Academy of Sciences at Calcutta that “science alone can solve India’s problems of hunger and poverty, of insanitation and illiteracy, superstition and deadening custom and tradition, of vast resources running to waste, of a rich country inhabited by starving people.”

It was at Nehru’s initiative that the Congress party set up a National Planning Committee in 1939, and invited leading scientists to formulate plans for the scientific, technological and economic development of the country. Even when he was only the Interim Prime Minister in January 1947 (eight months before independence) Nehru laid the foundation for the National Physical Laboratory, India’s first national laboratory.

To give the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) a boost, Prime Minister Nehru himself assumed its chairmanship. He wanted to turn the CSIR, an institution set up in 1942 to do World War II-related research, into an instrument for the peaceful application of science in independent India.

According to Britannia.com, the CSIR’s major achievements include, the development of the Light Combat Aircraft (LAC) “Tejas” and the supercomputer Flysolver; the creation of a relatively cheap antiretroviral drug for treating HIV infection, and the organization of expeditions and research studies in Antarctica.

A number of national laboratories and research institutes were set up between 1947 and 1964, the year Nehru died of a stroke. Seventeen national laboratories, specialising in different areas of research, came up. Among them were, the Central Electronics Engineering Research Institute at Pilani in Rajasthan (1953); the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) in 1958 and the National Aerospace Laboratories in Bengaluru (1959).

Within a year after independence, Nehru set up the Atomic Energy Commission and established the Department of Atomic Energy. On 4 August 1956, the Nuclear Research Reactor APSARA was commissioned by the Bhabha Atomic Research Centre (BARC) near Bombay. APSARA was the first Nuclear Research Reactor in India and also Asia. Nehru was insistent that nuclear power be used only for peaceful purposes.

“The use of atomic energy for peaceful purposes is more important for a country like India whose power resources are limited than for an industrially advanced country. It may be to the advantage of countries which have adequate power resources to restrain the use of atomic energy because they do not need that power. It would be to the disadvantage of a country like India if that is restricted or stopped,” he reasoned.

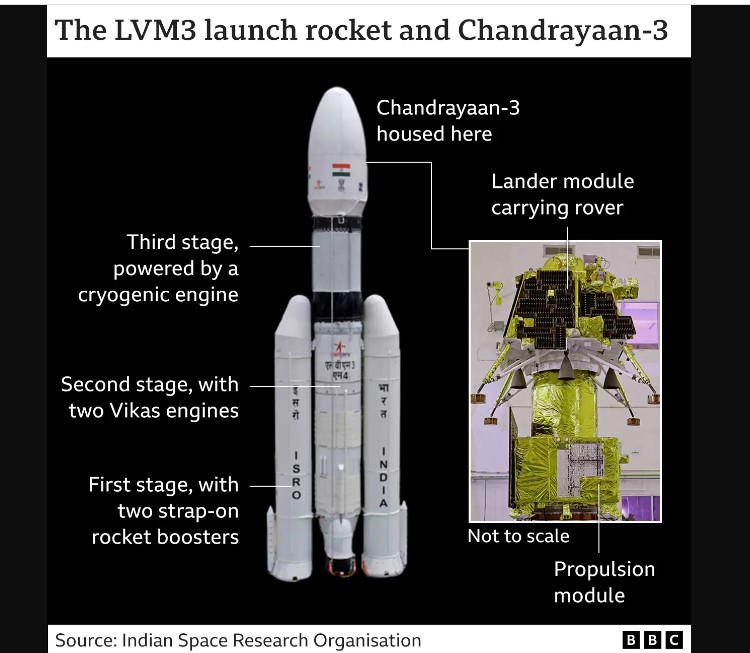

Nehru pioneered space research in India. The Indian National Committee for Space Research (INCOSPAR) was set up in 1962. It established a Rocket Launching Facility at Thumba (TERLS) in Kerala. In 1963, the first rocket was launched. This eventually led to the successful “Mangalyaan” mission to Mars in 2014 and the “Chandrayaan 3” mission to the moon in 2023.

In 1952, the first of the five Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs), patterned after the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in the US, was set up at Kharagpur in West Bengal. The other four came up later at Madras, Bombay, Kanpur and Delhi. By the last count, there were 23 IITs spread across the length and breadth of India.

Preveen Davar says the expenditure on scientific research and science-based activities increased during Nehru’s tenure from about INR 10 million in 1948-49 to INR 850 million in 1965-66. The number of scientific and technical personnel rose from 188,000 in 1950 to 731,500 in 1964. Enrolment at the undergraduate stage in engineering and technological institutions went up from 13,000 in 1950 to 78,000 in 1964.

Thus, Nehru laid the foundation for future Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s rejuvenated Atma Nirbhar (self-reliance) and “Make-in-India” projects.

Nehru did not set the natural, experimental and exact sciences in opposition to human sciences, says historian Madhavan. K.Palat, an editor of the Collected Works of Jawaharlal Nehru (Oxford University Press). Nehru’s concept of the “scientific temper” was akin to a “free soaring of the creative spirit”, Palat says in an article in The Hindu in 2021.

To Nehru, knowledge was the product of empirical investigation and logical reasoning, usually known as the scientific method, and any other process led to error. The philosopher, historian, jurist, or literary critic had to be as scientific as the sociologist, economist, or linguist; and, unlikely as it might seem, they had to be no less so than the mathematician, astronomer, and zoologist.

Nehru believed that the sciences admit of no “privileged knowledge”. He was thus firmly against its confinement to special classes or castes in society. The Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO), like other scientific institutions in India, has many people in high positions from humble, lower middle class and non-anglicized backgrounds. And these men and women have scored as many successes as those from elite backgrounds and elite institutions.

Nehru abhorred gender discrimination. No wonder, 58 of the scientists in the Chandrayaan 3 project were women.

For Nehru, the propagation of science and the scientific temper was linked to his mission to get his people to use scientific reasoning in whatever they did. Science he said, “liberated the mind from superstition, dogma, ritual, habit, and custom, and permitted it to explore both the infinite expanse of the universe of nature and the limitless internal spaces of the mind.”

In spite of the misuse of science for destructive purposes, Nehru believed that science and technology were inherently good and beneficial to mankind. Palat points out that Nehru “firmly adhered to the position that true knowledge alone could bring awareness of danger even if such knowledge could be perverted.”

Nehru regretted that scientists and laypeople tended to have a narrow and limited vision of science. He called for a broader vision of science.

“We live in a scientific age, so we are told, but there is little evidence of this temper in the people anywhere or even in their leaders,” he noted and added: “The true scientist is the sage unattached to life and the fruits of action, ever seeking truth, no matter where this quest might lead him. For me, a true scientist is more spiritual than a man who may call himself religious and whose mind is limited by some religious values and does not go beyond it.”

(Courtesy Daily Mirror)