By Uttam Sen

Life’s medleys can grow so diverse that every time a story is told it could differ from the last.Let alone contrasts between region and country, people from one part of a city can be poles apart from those from another. This is pronounced in places in which there has been indiscriminate relocation over time. That diversity even split the country, though there is reason to believe that indigenous blending was disrupted and the discord manipulated.

One particular vista fortuitously presented itself. During a visit to Dhaka on election coverage I had met the person in charge of the Jamaat-i-Islami office. The austere bearded cleric received a colleague from a North Indian newspaper and me cordially. We had gone there to specifically inquire into reports of violence against minorities following the Bangladesh Nationalist Party’s triumph over the Awami League in national elections. He vociferously denied involvement of his own outfit. But beyond the politics I had detected an unmistakable twinge of nostalgia in our interlocutor’s voice as he recalled that central Kolkata, where both us Indian journalists happened to have lived up to our youth, was also the neighbourhood where he had been born and raised many years earlier, before Partition.

Indeed, loitering around out-of-bounds areas with friends in Dharamtala on “hartal” holidays in the late ‘Fifties was great fun. We could have been roaming a ghost settlement. I wondered why buildings which had definitely seen better days stood cheek by jowl in such disrepair. They were probably property which had passed under a cloud in the Partition years.

Sure enough, a little probing revealed those hungry stones had tales to tell, though they pertained more to where I lived rather than the spectral wonders that had aroused my curiosity. The thoroughfare below our flat, then S N Banerjee Road, was once Corporation Street, the City Municipal Office being located close by. “Corporation Street’’ was one of the three places mentioned in the secret report of the British Governor, Frederick John Burrows, to the Viceroy, Lord Wavell, on the Great Calcutta Killing. ‘’The situation was bad in Harrison Road (now Mahatma Gandhi Road in north Kolkata), Wellington Square (at the present time Subodh Mullick Square in Central Kolkata) and Corporation Street”, he wrote[i]. Across Chowringhee (many-coloured) Road, presently Jawaharlal Nehru Road, to the west was the Maidan.

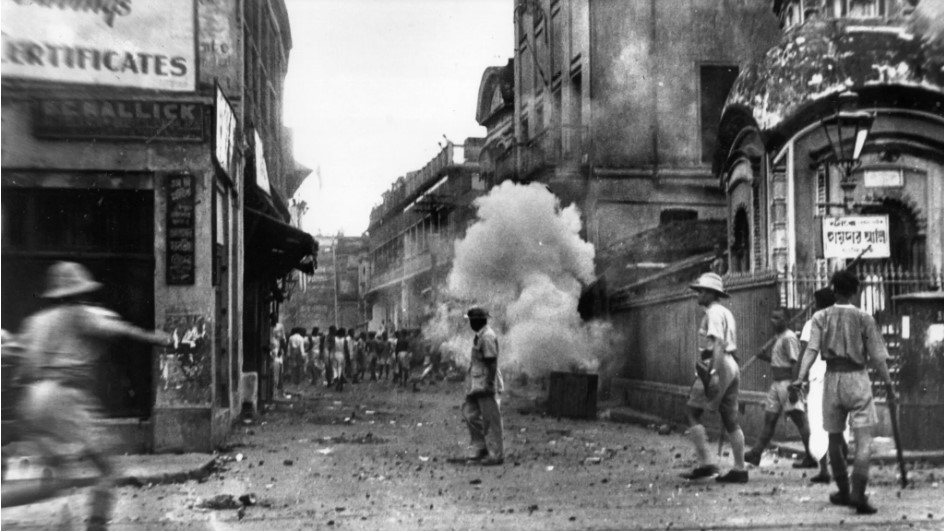

Pictures of the riots show horrific scenes of dead bodies strewn across Chowringhee Road adjacent to the Grand Arcade flanking Grand Hotel. Diagonally across stood (still does) the 150-feet- plus column of the Ochterlony monument, commemorating a military officer of the East India Company who distinguished himself in the Anglo-Gorkha war in Nepal, currently renamed Shaheed Minar or Martyrs Column. Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy had been among the Bengal Provincial Muslim League orators, and future Pakistani Premiers, who had addressed a mass rally from the ground there. Another was Khawaja Nazimuddin, “Prime Minister” of Bengal from 1943 to 1945, later Chief Minister of East Bengal, Governor General of Pakistan and then briefly Prime Minister. He was to eventually run into the same kind of dead-end that Suhrawardy did.

I do not know what the premises looked like then (or do now) but in my early years at least one first division cricket club proclaimed its existence by its tent adjacent to a scantily grassed surface as its ground. The outer periphery of Governor’s House or Raj Bhavan was not very far away, diagonally across the road. My brother and I regularly traversed the way past Ochterlony monument on our way home from football matches in the Maidan or on the red letter days of a Test match at the Eden Gardens.

The ambience on August 16, 1946, would have been starkly different. After the Muslim League leaders had spoken, mobs had fanned out towards the city. “Corporation Street” and its parallel Dharamtala Street (for the places of worship on it), rechristened Lenin Sarani, were almost definitely the arterial routes that the processionists took to creep into dense indigent roadside backyards where they would have wreaked havoc on the helpless unless confronted by their communal counterparts, which happened from time to time with blood-letting of a different kind and scale.

The author of the best-selling City of Joy, Dominique Lapierre, had written or said somewhere that Kolkata’s slums could give Harlem a run for its money, or words to that effect. There were many of them in the aforesaid region’s nooks and corners.

The mayhem expedited Partition, that too with rushed and often amateurishly mindless demarcation of borders. People in a hurry to show results were vindicated but they plunged the eastern region in particular into a state of disorder and dysfunction.

Our building had its own architectural distinctiveness owing to the past in which the ground and first floors housed a famous departmental store. There was an uncovered area on the second floor which was surrounded by servants’ quarters on one side and corridors and residential flats on the three others. The rarity of the second floor cement- courtyard-like space was that a large part of it was the atrium of the shopping centre below. The departmental store there was the raison d’etre for the building itself. In our time most of the first floor housed a bank. The ground floor, once also the departmental store, was dominated by the United States Information Service (USIS), apart from a cottage industries emporium, a chemists’ shop and sundry other small set-ups.

In that part of town in those days domestic help did not always emerge from the immediate countryside. They could have had distant origins. Their demeanour told of a real mixed bag. They did not have “prestige” vis-à-vis the “gentle” breed but they were generally very proficient, even well- traveled. Erstwhile Central Calcutta was a different kettle of fish from most of the city, particularly when the port was functional.

Over the generations the cargo had included human labour imported from Africa as slaves in transit to forbidding destinations or indentured workers from the hinterland en route to other parts of the globe. Of course this was incidental to the staple industrial freight. Calcutta is believed to have absorbed some of the human resources. About sixty years ago there were cooks and waiters who had slipped out of their ships in search of employment.

A caring writer has said that no foreigner could really come to grips with the cryptic city any more than a permanently static resident could celebrate its mysterious, contested, ineffable richness without stepping out and realizing its distinctiveness. The contestation is well-known. To me Kolkata/Calcutta, as I have known the city, gives me both the pain and pleasure similar to what I felt after going through the disparities of Harlem and Broadway in New York.

To take just one example of the harrowing part, the land around Fort William off the Strand, and its extension into the Maidan, sometimes has an idyllic rolling countryside aspect. That area was a bustling human settlement on the river, swept clean by the early colonialists.

The Maidan that transpired has been the lungs of the city and a wellspring of joy and happiness, even spectacle and grandeur, with parades and international sporting events. There was a picturesque lake with boating facilities next to the cricket stadium, predictably a popular holiday destination. It was subsequently filled up. On Sundays a vast portion between Outram Street running roughly east to west and Victoria Memorial on the western extremity was a free- for- all, first -come –first- serve, impromptu, open air, cricketing coliseum where people went with their gear and captured a spot to play the game. We did so ourselves. The place has been a happy hunting ground for us hoi polloi. But knowledgeof the past, which we did not have, could be more than sobering.

To take the narrative a tad closer to the references I have consulted, including several books and a documentary I received over social media, the building that was the setting of my primary remembrances was the cover story.

We had seen Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali (Song of the road) under some pressure. In our time Bengali parents would have their children see the films of Satyajit Ray and read the editorials of The Statesman newspaper even if they both flew above our heads. But we happened to see the young protagonist Apu from the village telling his mother about the sights of the big city, one of which was the Whiteaway Laidlaw building, the place where we stayed, the name mutating with every change of ownership. It was Sachidananda Chambers and the Metropolitan building in our time, after the owner and Metropolitan Insurance which gave way to the Life Insurance Corporation of India. Before Independence the residential quarters were called Victoria Chambers.

Sachidananda was, to the best of my knowledge, the father of the owner shortly after Independence, also proprietor of the Banga Lakshmi Cotton Mills, whose polished brown wooden signboard adorned the entrance to the first floor office at the elevator landing from one of several entries to the building. This access opened to a lift or elevator to the top residential floor and came via the by-way to the garage. There were eerie gaps in my understanding of the episodic interconnections but later academic references clearly bear out that the Mills were a symbol of the Swadeshi economic resurgence in Bengal.

There was bustle in and around the neighbouring street-side shops and eateries, run by people from Bihar and UP who were predominantly Muslim. Close to the north and the west there were some Sikh restaurants whose fare was comparable to the best.

Sometime in the late ‘Seventies a friend of mine was the Punjab Government’s Liaison Officer in Kolkata. He unexpectedly got word that his Chief Minister would be coming to Kolkata. Among other things, he happened to have heard of those dhaba-like restaurants in and around Chowringhee which supposedly served authentic cuisine. Apparently a gourmet he wanted the IAS officer to arrange for a lunch there. He would go incognito, without VIP security cover. The preparations gave my friend a nightmare. But on the day the formidable public figure was just himself, a voracious foodie, and passed for any other robust gastronome from his community. The outcome was rewarding for my friend as his boss went back happy with the meal and the experience.

After the bend in the road, interchangeably Esplanade, Dharmatala and Lenin Saranee, to Esplanade East towards the north-west which covered the regal Raj Bhavan on one side and office spaces on the other, the city’s non-residential sector looked very different from today. Sparsely populated, clean, prim and proper during working hours, the area appeared the part of a quietly happening place. Esplanade East not only led to Writers Building, now a heritage site, but then and many years after, the State Secretariat. More importantly for us the location included the Great Eastern Hotel, legendary for the many famous people who stayed there, not the least of them Test cricketers, because the place was the five-star closest to the Eden Gardens.

Those days Calcutta’s streets were washed by hose pipes in the morning and retained a certain gloss through the day. After dusk and on holidays durwans lazed on their pavement khatiyas (jute string charpoys). In my imagination they were suggestive of the zamindari lathiyals (stick-fighter henchmen) of old.

Back at the Dharmatala locale, where Chowringhee Road bisected Esplanade, was the Tipu Sultan mosque built by his son, exiled along with his family to Calcutta from Mysore by the East India Company. Alongside hawkers stalls , a low cost eatery and paan shop dotted the gully to the majestic landmark of Statesman House. The newspaper from which the building got its name was once considered sacrosanct for the credibility and objectivity with which it reported the news. An event was considered authentic only after the newspaper confirmed it. Ethnically attired in sherwani and waistcoats the turbaned “Kabuliwalas” congregated in the evenings for supper and picking up the day’s news and gossip in a rough-hewn eating place in the lane. They had been locally immortalized by the film on a Tagore short story by the distinguished film director Tapan Sinha. That was also my path at any time of day from home to office. The formal route would be along Jawaharlal Nehru Road which after the Esplanade intersection becomes Chittaranjan Avenue, the Central Avenue of old.

The neighbourhood was demographically amorphous, more rag-tag than crème de la crème, particularly on the streets! Like most metropolitan places the city centre was not dominated by the local Bengali ethnic majority. My brother and I had friends who were Maharashtrian and Punjabi, children of middle class professionals like our parents. Our neighbours for a while were Tamilians, the family of a top-flight official of the public sector financial institution that took over the building. The question of ethnicity never cropped up. But even at below ten years of age I felt a yearning to define myself.

In the building we spoke in English and Hindi with our peer group and more English and Bengali in our missionary school in nearby Park Street. (According to our family lore, our father was consulted by the prospective owner’s son on the assessment of the building at the time of the purchase.) At home the tongue was Bengali. When we first went there the building was still famous for having housed the British departmental store which was no longer there, but distinguished enough for George Orwell to have observed in his novel Burmese Days that the basic kind of place he was quartered in was no Whiteaway Laidlaw. A friend’s family history, with Myanmarese (Burmese) links, bore out that Rangoon (Yangon) had a branch which was premium brand.

Perhaps understandably, I did not feel entirely cosmopolitan. Much later, after a visit to the USA I realized I was conforming to an unstated, universal human standard. People were “American” in public but culturally true to their place of origin at home. Likewise, the mix we saw in our building was more salad bowl than melting pot. There were British, Dutch, an Indo-German couple and Sri Lankans (then Ceylonese) in the building, alongside Indians and Anglo-Indians.

A Scotsman owned a famous garage which dealt in cars, a Brit (perhaps also a Scotsman) worked in or owned a renowned jewellery outfit nearby, the Dutch were employed by a prominent airline, the German lady and her Bengali husband were doctors, the Anglo-Indians were directors of the Tramways and the Fire Brigade and the Ceylonese, now Sri Lankans, were a retired couple but very popular socialites. For whatever reason, their friendliness was almost unreal, particularly with us youngsters. It was probably the urbanity of the time.

Speaking for myself, I did not have much of a determinate identity. Yet my genes seemed to turn up. Brought up in West Bengal but of cut and dried Barisal descent from the patrilineal side, I always felt that the spontaneity of the people from my mother’s family who spoke the rich and expressive Dhaka dialect was closer to my persona than the other.

Sonar Bangla’s verdant green laced with waterways echoes the name “Bengal”, the suffix “al” originating from the country of “khals”(canals). You see that aspect more clearly on the other side of the border, as I did when I went there. By most accounts the ravages of time and changes in the course of waterways have taken a greater toll of our western sector. Confusion was worse confounded by a (false) stroke of the pen which disrupted a people and their way of life. Yet I could not help feeling that as long as the finer points of a legacy are kept alive there will be light at the end of the tunnel.

We did not suffer any physical violence or damage like many others but whatever little ancestral networking/bonding and property a middle class Indian musters by way of material and psychological continuity, sustenance and cushioning, were gone. We had no “gaon” to go back to. To be sure there were alternative arrangements, like having grandparents re-settled in a remote idyll called Rupnarayanpur in Asansol, an appendage of the Chhota Nagpur plateau, as far from the madding crowd as possible, to recreate the Barisal they had to abandon. But for better or for worse, life could not have been the same as at the original hearth and home.

I am not sure whether what we lost in the swings we gained in the roundabouts. I was raised under the watchful eyes of sedulous parents, one an architect and the other a housewife and honorary social worker, with a younger brother in tow. Like a few million displaced by Partition, we had been severed from our roots. But our circumstances were ostensibly good enough to arouse envy outside.

I did not see much of my own Bengali bhadrolog stock, blissfully ignorant that some compatriots and scholars felt we were on the verge of extinction had Kolkata, then Calcutta, gone to East Pakistan as demanded by the Muslim League. The brilliant “Deshbandhu” (Friend of the country) C R Das saw through the British gameplan to eventually reduce the Bengali Hindu to a minority, without quite succeeding in scotching it. Yet people must have wondered at the temerity with which Bengal was divided into Bihar, Orissa and Assam (and Bengal) in 1912. It takes all sorts to do the world’s work.

This was overshadowed by the alibi of transferring the national capital from Calcutta to Delhi on administrative grounds. The question of being reduced to an ethnic or religious minority would not have arisen without the abrupt division, to many a divide-and-rule reaction from the rulers to a burgeoning vanguard of national consciousness and intermittent terrorism. In a society as heterogeneous as our’s, identity considerations can always have been politically exploited as it was in Bengal to the dismay of those who were looking forward to a Brave New World. Something completely new and different did happen India was first off the mark with independence in Afro-Asia after the Second World War and a trailblazer. But the seeds of dissension had been planted.

At the outset the Bengali’s departure from States where he had either been posted on government service, worked as professionals or simply grown up as sons of the soil, created difficulties for the ordinary local citizen. In due course, the Partition of 1947 left an exposed chicken’s neck to sustain lower and upper West Bengal with Bangladesh on one side and Bihar on the other. Established systems of trade and transit were disturbed and a practice like workers moving into plantations as begun by the British became cross-border international movements.

I do not know whether the proposition is actually maintainable but I have come across the hypothesis that the 11th-12th century Senas had created an eastern Indian lebensraum within a natural eco-system almost like the Vijaynagar empire in the South. I have heard Sri Lankans saying they are descendants of those people. West Bengal’s second post-Independence Chief Minister, Dr B C Roy, brought up in what was Greater Bengal and became the separate state of Bihar, was believed to have briefly tried to unite Bihar and West Bengal.

To extraordinary Bengalis the world is their oyster, as they create human capabilities across the board. The shortcomings of cartography can be surmounted in the mind at a time when the computer conducts intercontinental warfare, monitors satellites in space and eventually engineers human genetics. Physical space is no longer the bottom-line for human interaction, even for trade and business. The Asia-Pacific can potentially open up a new horizon, arguably for the entire eastern coastline.

Yet bitter-sweet as they might have been, memories are sacrosanct. I found a Facebook post by a contemporary too enthralling –and relevant — to resist. He quoted Salman Rushdie to say:” my present is foreign and the past is home, albeit a lost home in a lost city in the mists of lost time”. The tenanted flat in which I was brought up, and its environs, comprises the past for me.

Footnote:

[i] Ian Talbot, The Great Calcutta Killing, 1946, British Library Website, Transfer of power, 1945-47, article published on November7, 2022.