December 6 (CNN) – I’ve been visiting Saudi Arabia for close to two decades and in that time I’ve experienced some incredible things.

I’ve climbed the scarily steep and staggeringly beautiful mountains of the south. I’ve scuba dived the immaculate Red Sea coral reefs off Saudi’s western coast. I’ve driven rally cars over the dunes in the north. I’ve visited ancient wells. Spent freezing winter nights in the desert cooking food with red hot fire embers buried in the sand. And I’ve walked barefoot along the kingdom’s eastern shores on sweltering summer evenings.

I’ve flown in flimsy microlights, soaring serenely above rich farmland. I’ve ridden tactical combat helicopters missions, skimming the desert floor and banking hard around sand dunes.

Yet none of these has affected me as much as the moment I felt Saudi change.

It’s no exaggeration to say that the recent social upheaval in the country has been profound and fast.

In 2018, I was in downtown Riyadh, chatting to people at a near-empty outdoor cafe in the early evening.

The religious police, once widely feared and respected, arrived by car, stopped at the roadside and started telling people to go to prayers.

Previously, this would’ve prompted an immediate reaction, with people obeying their commands.

This time, no one moved.

It was in that moment I connected with what Saudis had been feeling in the months since Mohammed bin Salman or MBS, Saudi Arabia’s crown prince, stripped these morality guardians of their power.

It was a sense of lightness, a freedom to make choices.

‘More fun’

That was two years ago. These days the religious police have mostly been consigned to desk duties. Decades of oppressive psychological pressure to conform to the conservative strictures of Islam have fallen away.

And today, freedom is blossoming, albeit still controlled by the invisible lines of most Gulf states: enjoy, have fun but don’t get ahead of the leadership.

Outdoor cafes along new festive looking pavements are abuzz with men and women out for fun, to meet, to shop, to chat, to relax.

Mounira Al-Qwait, a 20-year-old fashion designer wearing a traditional black abaya she styled herself, told me what this means for her.

“We have more fun now.. going outside for movies, going outside for the restaurants and meeting with friends,” she says, her eyes sparkling above a face-covering niqab.

Nearby, fashionably dressed without a headscarf (an omission enough to get her pulled off the street a few years ago), is Tutu, a 42-year-old kindergarten teacher. She told me she loved the sense of “freedom” and “more energy.”

“Now our lives as Saudis completely changed,” she says. “Actually from all the decisions taken by Mohammed bin Salman. All Saudis now is happy about all these changes.”

I was in town this time covering the global economic powers’ G20 summit. Saudis were the hosts of the November 21-22 meeting — a massive responsibility and challenge.

After it wrapped, I watched Finance Minister Mohammed al Jadaan lavish praise on his youthful team. The “wealth of the nation,” he concluded later.

His offices in the new Digital City district of Riyadh — a futuristic complex of buildings interwoven with cascading water fountains and open, airy pedestrian spaces — feels more like Dubai than the dusty Riyadh of old.

No turning back

Here change is abundant. Women work in offices side by side with men, something that was illegal until a few years ago.

Talia, 27, is one of them.

Raised in Riyadh by her single mom, she graduated from universities in both London and Beirut before returning in 2017 when the reforms began. “It was like weekly, almost daily, like there’s new announcements on the news coming and it was so exciting,” she told me.

Since then she’s worked with female CEOs and sees no limit to what women can achieve.

“We have a youthful crown prince and the country is youthful — like 70% of the population is under 30 — so I felt like the reforms were being made by us for us, so there’s no way that we’re going to go back.”

One of the chief reasons for the social upheaval in Saudi Arabia is MBS’s decision to challenge the clerics who’d given rise to the generations of orthodoxy, producing Osama Bin Laden, al Qaeda, and almost all of the September 11, 2001 attack hijackers.

MBS’s father, King Salman bin Abdulaziz Al-Saud is the latest in a long, ossifying line of leadership that passed from the nation’s founder King Abdulaziz bin Abdulrahman al Saud to his increasingly aged sons.

It took Abdulaziz 30 years to conquer the country’s four geographically distinct regions — Asir in the south, Al-Ahsa in the east, Hejaz in the west, and Najd in the center — and establish the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia on September 23, 1932.

It’s taken MBS fewer than five years to shake up the kingdom in a way his predecessors dared not, along the way arresting and detaining more 200 princes and businessmen he accused of corruption.

His vision of changing Saudi Arabia by 2030 demands a diversified economy and empowerment of the young.

Tough taskmaster

Ministers describe him as a tough taskmaster who will listen but won’t tolerate dissent once a decision is taken, or any failure to deliver on reforms he wants.

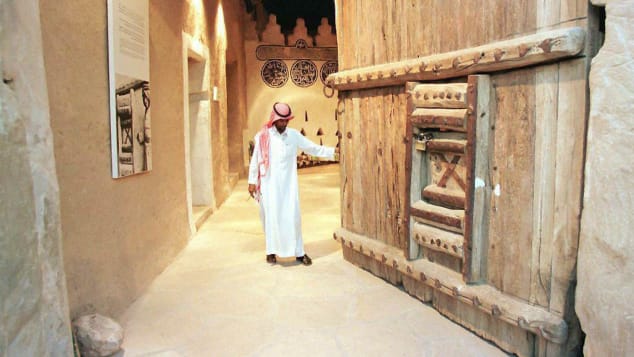

At Masmak Fort in Riyadh’s old quarter where in 1902 Abdulaziz began his campaign to build a kingdom under his control, a metal spear tip protruding from the ancient wooden gates is testament to the forcefulness of his historic actions.

MBS’s vision is no less robust. Human rights activists have been jailed, dissenters including journalist Jamal Khashoggi brutally murdered, yet MBS has such support for what he has done that so far the young seem OK with it.

“It’s an important [topic] that has been discussed all over the world,” Mohammed al-Ajwi, a 26-year-old accountant told me, referring to the killing of Khashoggi, which was eventually blamed by Saudi authorities on rogue operators within MBS’s inner circle. The crown prince has denied personal involvement in the killing, while US and other foreign intelligence agencies have assessed that he ordered it.

But al-Ajwi adds: “The government already said what they have and it was a clear answer for us the people of Saudi Arabia. So it was a mistake by a few people. That’s it for us.”

From Masmak Fort, a busy six-lane highway now runs to Digital City and a financial district where new eye-catching buildings are appearing all the time. When I first came to the kingdom in 2003, Riyadh had only two towers. Now there are dozens.

Yet leave the city and, in the harsh deserts of the Nejd region that surrounds it, you can still find the Saudi Arabia of the past.

White royal camels are tended on old farms. Beautiful lush grassed oases add intense doses of color. On rocky outcrops, ancient natural water cisterns vital for generations of herders are still in use.

I’ve been lucky to see all of this thanks to my job, but it’s about to get easier for everyone.

Last year, as part of his vision to diversify Saudi Arabia’s oil-dependent economy by 2030, MBS announced opening the kingdom’s doors to tourism.

Unexpectedly, it had a remarkable boom this year.

When the kingdom shuttered its borders because of the Covid-19 pandemic, Saudis went on vacation in their backyard. The country’s regions are so diverse, and the country so big, that it’s possible even for locals to feel they’re taking a break a long way from home.

Ancient marvel

Away from Nejd, there’s coastal Hejaz, home to Islam’s holiest sites of Mecca and Medina, which were already cosmopolitan and relaxed due to the influx of centuries of pilgrims.

Here, windows on upper floors of old homes jut into the street allowing cooling sea breezes to waft through rooms and inner courtyards, circulating over cool, refreshing pools.

To sit inside one of these modest houses is a treat I’ll never forget, a chance to relax away from cares and troubles outside.

To the south, Asir’s mountain peaks get snow in the winter, giving them an Alpine feel. In the summer they still offer a little respite from scorching deserts.

In the east where pan-flat desert meets the Persian Gulf, date orchards proliferate above an even more valuable commodity, the kingdom’s oil.

But the best treat to lure tourists is one I’ve yet to see — Hegra.

The site, sometimes known as Mada’in Salih, or Al-Ḥijr in the western Hejaz region was settled in the first century CE by Nabateans who carved great buildings into the rocks and left rock writings. It’s a site to rival Petra in neighboring Jordan, which was also built by Nabateans.

While Petra draws thousands upon thousands of tourists a year, Hegra is still uncrowded.

That could all soon change though.

And if MBS’s promises hold longer than a shimmering desert mirage, as the kingdom’s young population fervently believe, the world will find much worth discovering.

ADVERTISEMENT