By K.Venkataramanan/The Hindu

For those of us who remember the first flush of excitement that ‘Rajini style’ caused in Tamil society in the 1970s, style was the man. The idea that Rajinikanth, the superstar of Tamil cinema, is best known for his style has been with us for so long that not many associate his films with substance.

That some of his early films and performances showed promise is nearly forgotten. He has come to be associated with superhuman achievements. His mythic appeal has been converted into innumerable jokes about impossible feats.

The time has come when his fans and admirers have accepted his style as his work itself. This will be as true for his films as for his present foray into politics.

Improbable Hopes

“Style is art,” Susan Sontag said, questioning the distinction often made between style and substance, between form and content. Mr. Rajinikanth’s art, if the word can be associated with him, is his style. Sontag also warned against interpretation, calling it the “revenge of the intellect upon art”.

As the leading figure in the Tamil celluloid world takes the plunge into politics, it may be too early to interpret the actor’s politics and political intentions. Looking for substance or a political vision can wait. It is, for now, as futile as looking for deeper meanings and hidden subtexts in his fast-moving films with improbable fight sequences.

Questions are being raised: whether his entry will worsen the cult of hero worship and charisma-driven politics in Tamil Nadu; whether he is laying the ground for right-wing politics to take root in what was until now inhospitable terrain for it; whether he is self-driven or being pushed by other forces. All these concerns are no doubt valid and require answers. However, in the immediate social and political context of present-day Tamil Nadu, other questions have to be raised first.

Why does Mr. Rajinikanth want to enter politics? He says the present system is not right and needs to be changed; that there is political degradation in Tamil Nadu; that the State has become a laughing stock; that rulers have become looters; and that if he did nothing to stem the rot even at this stage, he would be wracked by guilt till his death.

It may appear that the situation he describes does prevail in Tamil Nadu after the demise of Jayalalithaa and the inability of Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) President M. Karunanidhi to remain active in politics for health reasons. The present All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK) regime in Tamil Nadu is quite unpopular by all accounts. However, are the rest of the claims of the politician-to-be true?

Politics did not suddenly degrade in the last one year and corruption is not a recent phenomenon. If something causes great shame and embarrassment to the people of Tamil Nadu, it is the ease with which film personalities, both the famous and the also-rans, enter public life and are seen as natural political leaders.

Most parties are led by those who do not create or tolerate a second-rung leadership and are virtually clubs run by individuals. Film stars have been floating political outfits based on individual popularity and converting their fan clubs into local units. There is little doubt that what Mr. Rajinikanth is planning is just one more party on this list. A party of one followed by numberless zeroes.

Endemic corruption has been punished by the electorate in the past. The verdicts of 1996 and 2011 in the State Assembly elections were clear mandates against the misdeeds of the AIADMK and the DMK regimes of the day. The State has a few core issues on which its interests are seen to be under threat, and parties, willy-nilly, have to take a position on these matters. It is difficult to avoid an issue-based agenda in the State.

It is true that the two main parties have done their bit to render elections devoid of issues by their election-time promises of freebies and, in recent years, rampant voter bribery. The mere absence of a tall leader capable of leading the State now cannot be used to make a claim that it has no ideological moorings or that Tamil Nadu is a ‘night-foundered skiff’ that can find safe harbor only in a new leader who does not have the trappings and baggage of its present political class. The truth is that Tamil Nadu voters are not so bereft of political options as some observers say.

Who Needs a Messiah?

It cannot be forgotten that despite phases of political instability, new alliances and coalitions within the political spectrum have come to power at the Center when the two main parties were unable to form the government on their own. The question is not whether Mr. Rajinikanth will be the State’s savior, but whether the State requires a messiah in the first place.

He has sought to project himself in a messianic role by claiming that he is not looking for power but only for guardians or sentinels of the exchequer to prevent plunder and loot. He said the battle has to be joined soon and that only cowards turn away from war. For good measure he quoted the Gita on one’s duty to wage war when required. The use of martial metaphors and the image of a protector or savior reveals a mindset that wants those governing to be patrons and the governed their clients. But this sort of clientelism is not something that can bring about any systemic change, but would rather entrench patronage and corruption.

As cynicism envelops the State, it is useful to remember that the only vacuum in Tamil Nadu today is the absence of a strong personality. Democracy can survive without such personages. All it requires is that individuals and institutions play the roles expected of them in adhering to the law and the Constitution. It is in the nature of democracy to appear inchoate in trying times. To believe that this is a systemic dystopia that requires emancipation by a messiah amounts to a disbelief in the fundamental nature of democracy itself.

This does not mean that the polity should shut out a newcomer. The much-reviled system can accommodate Mr. Rajinikanth and more of his ilk. But it is a stretch to say that the entry of those currently outside the political and electoral system is a dire necessity. Some have used the language of cinema to describe Mr. Rajinikanth’s political entry as the release of a blockbuster. It looks like he intends to play the deus ex machina that will enter in the final moment to resolve all the problems of Tamil Nadu at one go. The people may cheer at such contrivances on screen, but it is doubtful if they will do so in real life.

The Star and His Fans

Given the nature of relations between a hero and a fan, there is a credible fear that Mr. Rajinikanth’s presence may result in those backing him losing their political instincts and remaining blind followers with little concern even for the preservation of their rights. Some see his open espousal of ‘spiritual politics’ as a challenge to the core ideology of Dravidian parties. These are indeed portentous. But the danger here is not merely about right-wing politics taking roots. It is the movement away from a political legacy rooted in ideology to one that is solely personality-centric.

Even the foremost practitioner of charisma-driven and personality-centric politics, M.G. Ramachandran, built his popularity on a platform of welfarism and social justice. Mr. Rajinikanth represents a change the State does not need.

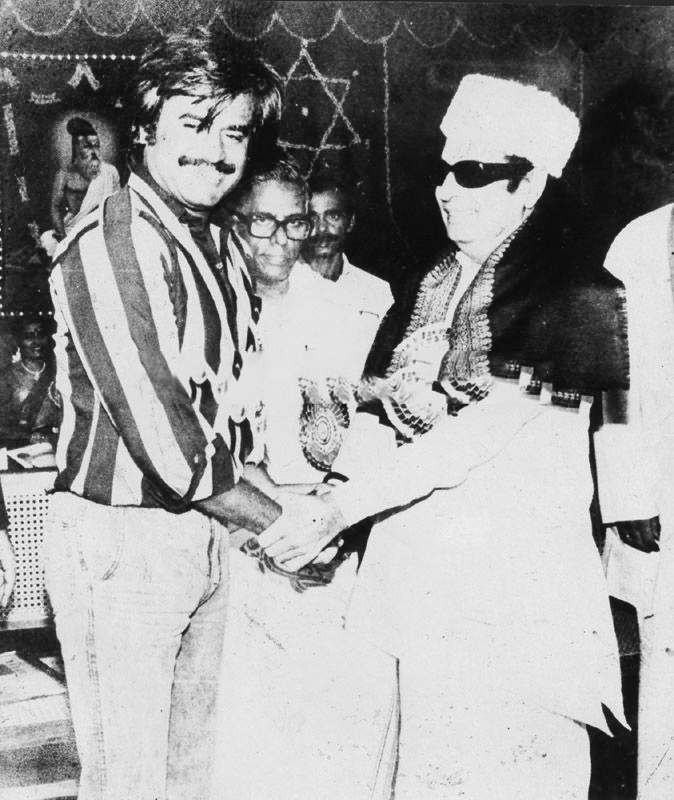

(Fans kiss a placard bearing Rajinikanth’s picture. Getty Images)