By Sasanka Perera & Dev Nath Pathak

New Delhi, May 6 (newsin.asia): Radio, in our view is not merely a matter of technology through which music, entertainment, information, news and increasingly fake news and many other forms of knowledge come to people. More importantly, by bringing all this, radio like all other forms of mass media also becomes a means of politics. When we refer to politics, we do not mean the contemporary popular understanding of the word that tend to denote divisive party politics in different national settings or across borders. Rather, we mean by it, a kind of social transformative politics of knowledge and ideas — whether actual programs on radio stations self-consciously tap into this potential or not.

And if there are intended politics by radio, there are also forms of cultural politics that come into being around radio. Such cultural politics engendered by radio programs, and listeners’ engagement with radio, could play a significant role in the formation of radio-communities across cultural contexts.

Communities of listeners in Sri Lanka, and in other parts of South Asia, could be bound by an invisible link created by waves of broadcasting. But this is not the same community that anthropologists have spoken of. The radio’s communities revel in partial anonymity, with partial unawareness of who all are tuned into radio to consume the same program. And yet, they are partaking on the same broadcast content, invisibly connected, and intangibly interacting with one another.

At times, the intangible interaction acquires tangibility as the anchor on the radio may announce the names of two or more listeners from different parts of the region sharing their sentiments and ideas.

It is in this latter broader understanding of politics that we would like to excavate two specific memories in this essay. One is the memory of Radio Ceylon itself and what it stood for in its time. The second is the iconic radio program, Binaca Geetmala, initially broadcast by Radio Ceylon, and later continued by the Sri Lanka Broadcasting Corporation (SLBC) when the former was renamed after the 1972 Constitution officially changed the name of the country. More specifically, what we have in mind is to explore briefly and reflect upon the cultural politics Radio Ceylon and Binaca Geetmala set in motion and to pose the question if such processes of politics is not possible in contemporary South Asia..

Cultural Politics of Radio Ceylon

Known as Colombo Radio, the precursor to Radio Ceylon was established in 1925 with the creative reuse of a radio transmitter ‘rescued’ from a sunken German submarine. It was effectively South Asia’s first public radio station. But the technical push that rapidly moved Radio Ceylon to write itself a more memorable history came in 1949 when the British military’s Radio SEAC managed by its South East Asia Command was moved to Colombo. Radio SEAC’s initial purpose was to entertain and provide information to British and allied troops in the region and beyond in the context of the Second World War.

In 1949, this World War Two military-cultural tool became Radio Ceylon. From this time onwards until its latter decline from the late 1960s onwards, Radio Ceylon’s sense of cultural politics and its interest in speaking to the world and to simultaneously bring the world of global culture to the region becomes apparent. It is in this context that V.S. Sambandan referred to this phase of Radio Ceylon as “when Ceylon ruled the airwaves.”

Radio Ceylon’s sense of politics can be broadly identified in the following three ways:

1) First, to usher in a sense of professinal programing to radio in South Asia at a time such practices were literally unknown. In this context, and with particular reference to India Sambandan notes, “for Indian radio enthusiasts of decades gone by, it was Radio Ceylon that set the standards” at a time when there were no commercial broadcasts in India for the purpose of entertainment. As such, listening to Radio Ceylon broadcasts was affectively “taking a break from the monotonous, though informative, broadcasts of All India Radio (AIR)…”

2) Second, to speak to, entertain and inform the local population (in Ceylon) in Sinhala and Tamil and also in English.

3) Third, to speak to South Asia and particularly to India in English and Tamil (for India’s South, and particularly to what is known today as Tamil Nadu) and later in Hindi/Urdu (for the Hindustani belt) when Binaca Geetmala began. As noted by Sambandan, “once tuned in, the listener was treated not just to music of the highest quality. The magnetic voices of broadcasters, Jimmy Barucha (English), Ameen Sayani (Hindi) and Mayilvaganam (Tamil), to mention just three, ensnared the listeners, taking Radio Ceylon to the top slot in the region’s radio network.”

At the height of Radio Ceylon’s popularity from the 1950s to 1970s, its following in India was considerable in addition to its local fan base. This was not only because of its offerings of Hindi movie songs via Binaca Geetmala as we will discuss later. But this was also because of the popularity of its English language songs and music from the West, which were not as readily available in India or elsewhere in South Asia at the time. As Nirupama Rao, the former Indian High Commissioner to Sri Lanka noted, “I first heard The Beatles over Radio Ceylon. We grew up listening to songs over Radio Ceylon.”

It is this sense of cultural politics, which stands out as Radio Ceylon’s global cultural sensibility and cosmopolitanism. Its programs offered an opening to the country’s presence at the time as well as a window to global cultural fare. As Sambanadan notes, “for Indians of the radio generation, Radio Ceylon was the first introduction to paradise-island and to the world of music.”

However since the late 1970s and more clearly since the 1980s there is a clear decline in Radio Ceylon’s and later Sri Lanka Broadcasting Corporation’s popularity both locally and in India. The reasons are quite similar.

The introduction of Vividh Bharathi, All India Radio’s commercial services offered an initial challenge to Radio Ceylon by presenting similar programs. It is no accident that Binaca Geetmala also moved to Vividh Bharathi and from Colombo to Delhi in 1989. On the other hand the cheap availability of prerecorded audio cassettes with popular music from 1970s onwards offered alternatives to Radio Ceylon’s programs, which people could listen to at their own time.

From the 1980s onwards the advent of television, private radio stations and finally FM stations also offered many more alternatives. These same conditions impacted the station’s local standing too. Equally crucially, over time, Sri Lanka Broadcasting Corporation could not live up to the standards Radio Ceylon had set in its own time. This was partly a matter of too closely entangling itself in the affairs of the state.

Also, as noted by Sambandan, “SLBC lagged behind the times.” The ideal as he further notes should have been for SLBC to “leverage its past and harness itself to the current developments in radio broadcasting.” This has simply not taken place.

Cultural Politics of Binaca Geetmala

The cultural politics of Binaca Geetmala has to be understood in the context the broader cultural politics of Radio Ceylon. Binaca Geetmala was a weekly program of radio countdown of Hindi cinema chart-busters blended with interesting infotainment on Hindi cinema anchored by Amin Sayani in what may be called ‘Hindustani,’ a mixture of Urdu and Hindi languages. It was aired via shortwave by Radio Ceylon from 1952 to 1988, and from 1989 to 1994 on All India Radio. Its peak however was during its run at Radio Ceylon.

The program had songs creatively interrupted by commentaries in the sonorous voice of Amin Sayani. The commentaries gave entertaining details of the songs, lyrics, and the singers. In other words, the songs were not merely presented for entertainment. They were also situated in their boarder socio-cultural context via the kind of information referred to above. The dramatic affect of the program was entrenched by fine editing and mixing. The songs that were added anew in each program were welcome with a bugle sound, which became iconic, and the songs, which stayed on in the program for many weeks, were also given an extraordinary bugle sound, an acoustic salute, referring to their longevity.

The memory of such an instance opens the locked secrets of cultural mobility beyond national territorial borders in South Asia. It also hints at the socio-cultural predilections toward something, which nation states might not have favored. After all, the Binaca Geetmala was not conceived by All India Radio (AIR), BBC, Voice of America or any other such national broadcaster of a powerful country with a variety of programs in different languages catering to linguistic communities across the world. These can only be seen as programs of power projection, which powerful countries have conventionally undertaken as in the case of BBC’s Sinhala, Hindi and many other language services and All India Radio’s Sinhala Service. Instead, Binaca Geetmala was a creation of Radio Ceylon, the national broadcaster of Sri Lanka, a country that had no interest or possibility of power projection across international borders. Nevertheless, in practice, Radio Ceylon, became a household name in the length and breath of India, which moved, The Hindu in a 2006 essay to describe the phenomenon as “when Ceylon ruled the airwaves.”

In the political context in which Binaca Geetmala was conceived, it was a veritable godsend savior for Hindi cinema music lovers. In 1952, the same year that the program first aired, the government of India had banned Hindi cinema songs on All India Radio indicating its thinking on culture in extremely puritanical terms. B. V. Keskar, the Minister of Information and Broadcasting in the cabinet of Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, was of the view that Hindi cinema songs will pollute the cultural sensibilities of post-independent India. At the time, it was state policy to encourage only what was thought to be pure, authentic, traditional, and classical music on the national radio in India.

It is in this specific context that the team of Binaca Geetmala approached Radio Ceylon, and quickly made arrangements to air the program from Colombo. Being hosted by the national broadcaster of Ceylon owned by the Ceylonese government, and that too to broadcast a genre of songs and music self-consciously banned by the Government of India on its own airwaves was quite a bold decision. It showed that democratic and independent decision-making was possible in Ceylon at the time even when it came to issues that literally crossed international borders.

Crucially however, this was the realm of culture and not politics as it is popularly understood. Nevertheless, the decision to broadcast Binaca Geetmala was clearly a political decision as it was also a subversive decision on the part of a government-owned radio station of a small country. It was a matter of very casually disregarding publicly stated cultural sensitivities of its bigger neighbor across the ocean.

The songs of Hindi cinema that Radio Ceylon broadcast were also received well by Sri Lankan listeners as well as audiences across India to whom the program was specifically targeted. This is in addition to secondary audiences in Nepal, Bangladesh and elsewhere in South Asia where short wave radio could reach, and where a taste for Hindi cinema songs was already established.

The growing listenership in Sri Lanka is particularly intriguing where Hindi is neither spoken nor understood. But it is Radio Ceylon’s Binaca Geetmala that played the most crucial role in popularizing Hindi film songs in Sri Lanka. In turn, this also ushered in another important dynamic of cultural politics. That is, the wholesale adaptation of the melodies of the most popular of these songs, to which Sinhala lyrics was introduced. For a short time in the 1960s the Sri Lankan government explicitly banned the practice of adapting Hindi movie song melodies for Sinhala lyrics. But given the porousness of the realm of culture, this was not a ban that could be sustained over time.

But the popularization of Binaca Geetmala and Radio Ceylon in India arose for different reasons. At one level, this phenomenon was not surprising since there was already a practice of Hindi language announcers joining Radio Ceylon to work in its Hindi service since the early 1950s. Partly, this was a lingering practice from the colonial era where colonial citizens could travel across to any country in the empire and particularly the region without much of a difficulty. This was also the time, the kind of restrictive nationalisms that took root in the region later, had not yet made its presence. So crossing borders and working across borders, particularly in the realm of culture was not embedded with the kind of anxieties one would experience today.

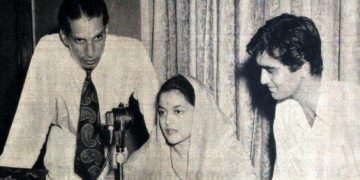

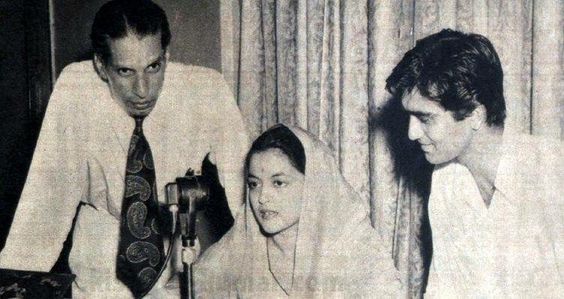

Also, as the earliest radio station in colonial South Asia, Radio Ceylon was a signpost for many artists willing to contribute to the realm of sound-art. Among many, Sunil Dutt was one of the announcers in the Hindi Service of Radio Ceylon. Later, Dutt became a well-known Hindi cinema star when he joined the film industry in Bombay. In other words, for listeners in India (not only in its Hindi belt, but in other language regions too), Hindi programming from Ceylon was a matter of ‘listening to the sounds of home’ and familiarization of the comfort-zone of home that were nevertheless emanating from beyond the borders of home.

More crucially, when this popular genre of songs was banned on All India Radio in 1952 as referred to above, Radio Ceylon was the only publicly accessible service, which offered such fare.

Besides all this, such a program also meant the production of commercial jingles for various products sold in India that added to the revenue of the government of Ceylon and later, Sri Lanka. On the other hand, Radio Ceylon also offered to Indian listeners music of the world through its very cosmopolitan English language service as referred to in the earlier section.

The transnational significance of the Radio Ceylon mapped a popular soundscape of South Asia. The popularity of Radio Ceylon and its presentation of popular Hindi cinema songs forced the cabinet of Pundit Jawaharlal Nehru to rethink its ban on cinema songs on the All India Radio. As a result, it decided to reinstate film songs on AIR in 1957. Moreover, All India Radio also started a special service called Vividh Bharti, which was dedicated to the songs of Hindi cinema was a direct response to the challenge from Radio Ceylon.

One of us (Dev Nath Pathak), as a growing boy in a small town in remote northern Bihar has anecdotal memory; Listening to radio was an important, and generic aspect of growing up; and amid various radio programs, it was particularly important to listen the Radio Ceylon. More importantly, the channel never appeared to be non-Indian and Ceylon seemed more like another town located somewhere very near though territorially afar. And despite the return of Hindi cinema songs on All India Radio later, Radio Ceylon remained popular among listeners until its pronounced decline.

Concluding Comments

In his 2006 essay on Radio Ceylon, Sambandan begins his discussion with the following observation and question: “Once the pride of the region, Radio Ceylon is today a fading memory. Can the Sri Lanka Broadcasting Corporation regain its lost glory?” Sambandan’s reflections are an apt place to conclude our own thoughts.

There is no doubt that Radio Ceylon’s and Binaca Geetmala’s pioneering role in the soundscape of South Asia and particularly in India have been overtaken by radical cultural and technological transformations as briefly explained earlier. In this context, Radio Ceylon’s contemporary manifestation in the form of Sri Lanka Broadcasting Corporation, has become irrelevant in the South Asian soundscape since Binaca Geetmala went off the air in 1994.

Nevertheless the memories and histories of these earlier institutional innovations can be the ground for fertile thinking in the larger scheme of South Asia today. One source of memory is various recordings of Binaca Geetmala (particularly) which appeared in cassette and LP record forms, and now available on online music portals. These recorded programs remind a listener of what happened then. They concretize the listeners’ sense of nostalgia.

Even now, the Sri Lanka Broadcasting Corporation continues to have a Hindi Service and continues to receive letters from India requesting songs. But unlike in the past, the service now plays older songs produced before the 1970s and its listenership’s general age is about 50 years. The youth are not a part of its depleted fan base.

This brief history reveals a number of issues. One is a typical commonsense anxiety that popular music is a threat to traditional forms of music such as the folk and the classical. The nation state as well as some sections of the public operated on the premise of this anxiety. Efforts were made to protect what was thought of as the ‘authentic-traditions’, as in the case of the Indian example of banning Hindi cinema sings referred to earlier. The second alludes to the industry as well as a creative radio station such as Radio Ceylon, despite being owned by the Ceylonese state, catching up faster with the pulse of people than hegemonic and conventional national politics. This was evident from the soaring popularity of Radio Ceylon and its programs including Binaca Geetmala in India and Sri Lanka in particular and elsewhere in South Asia more generally. And the third refers to the fact that popular music travels across borders, and is capable of carving a sizable fan following, and also synergized diverse locals.

These three issues, put together, underlines the trans-local implications of what Radio Ceylon once stood for. It created a dynamic soundscape of South Asia inspite of the borders thrown up by nation states and the boundaries of minds. Radio was a window to the world and to the self. Radio Ceylon’s history, if understood within the nuances it offers, would provide and ideal basis to engage in cultural politics in contemporary times, albeit taking into account and addressing prevailing conditions, tastes and modes of broader politics.

(The featured image at the top shows a young Sunil Dutt listening to Hindi film star Nalini Jaywant speaking over Radio Ceylon)

( Authors Sasanka Perera & Dev Nath Pathak are from the Department of Sociology, South Asian University, New Delhi. This essay, drafted to organize the preliminary ideas for broader research project by the authors was initially published in Guvan Viduli Sameeksha, Volume 3; February 2020 published by the Department of Cultural Affairs, Government of Sri Lanka)