By Dawn staff, Hufsa Chaudhry and Hasham Cheema

Lahore, January 16 (Dawn): Will Pakistani universities ever draw the line on moral policing through enforcing dress codes on female students? In continuation of what appears to be an endless pursuit to produce morally upright and ‘decent’ students, local universities time and again have shown their enthusiasm for stepping into the realm of policing attire.

Recent events demonstrate that this trend is thriving.

Earlier this week, the University of Agriculture Faisalabad announced that it will celebrate ‘Sisters’ Day’ on February 14 by gifting scarves and abayahs to female students.

A similar trend was witnessed last year when a faculty member at the Institute of Business Management (IoBM) shared her experience of being policed for her attire by a security official at the gate.

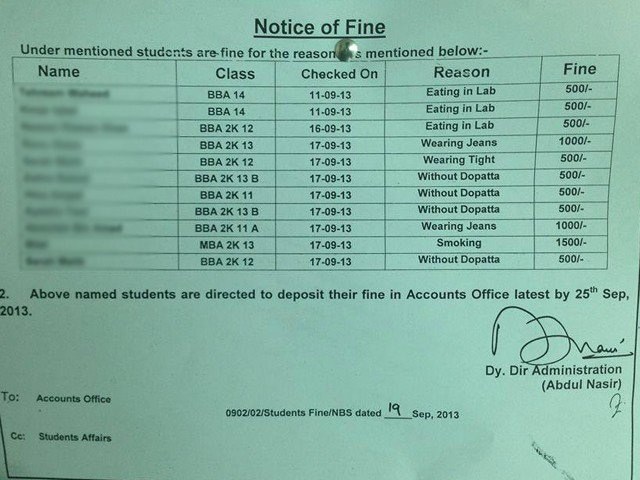

The debate around the politics of problematic dress codes emerged a few years ago when female students at the National University of Science and Technology (NUST) were named and shamed for wearing jeans, tights and not wearing dupattas.

NUST distanced itself from the incident when it came to light after a student who was targeted shared the notification on social media.

Also last year, Punjab Higher Education Minister Syed Raza Ali Gilani proposed making hijab compulsory in colleges in the province. His proposals ─ which were disowned by the Punjab government ─ included the giving of incentives to wear the hijab by rewarding female students who had fallen behind in attendance or marks simply on the basis of their head covering.

Again, the International Islamic University Islamabad said it had started enforcing a ‘decent’ dress code for its female students ─ in which wearing a dupatta or scarf is compulsory ─ in the management sciences department.

A university rector explained that the need for the dress code for the department arose as it was in an isolated location from where women walked to other departments.

“There are a significant number of male teachers in this facility,” he had said by way of explanation.

It wasn’t always like this (scroll down for more on that). But alas, it is today.

Here’s a list of dress-codes adopted by popular universities across the country.

IoBM

The institute asks female students to wear “modest” clothes. It specifies that female students can only wear jeans with knee-length shirts and must “avoid transparent materials and short lengths for sleeves”.

Bahria University

The university identifies shalwar kameez as a staple for female students, but does not permit male students to wear the national dress ─ except on Fridays.

“A dupatta/scarf is compulsory with all dresses,” the rules say. Again, for female students, the length of the shirt is specified ─ “jeans/trousers with long shirt/kurta (knee length)” are permissible. Tights are not allowed.

“I cannot understand why we can’t wear our national dress. Shalwar Kameez is part of our culture. Is Bahria not a part of Pakistan?” asks Umar, a student at the university.

Muhammad Ali Jinnah University (MAJU)

The university has divided its dress code into “desirable”, “admissible” and “strictly not allowed” articles of clothing.

For females, shalwar kameez are the desirable outfit, while jeans with kurtas and shirts are admissible ─ with a dupatta. However, jeans with t-shirts, sleeveless shirts of any kind, see-through and skin-tight clothes are strictly not allowed.

Males at MAJU have a wider range of desirable clothing options to choose from ─ trousers with shirts and shalwar kameez. Wearing jeans and t-shirts fall into the admissible category for male students. Interestingly, skin-fitted jeans and trousers, long hair, wrist chains and earrings are strictly not allowed.

Iqra University

Surprisingly, the university has a heavily-regimented dress code for males in comparison to female students.

NUST

Nust’s dress code, which applies to both staff and students, appears to be an anomaly ─ the same codes apply to both male and female students. However, this university’s dress code reveals another issue prevalent with dress codes ─ that of vague and undefined terms to enforce rules.

The rules are in place “to maintain academic dignity and sanctity of the institution”, it says.

“Students and staff of the university are required to wear decent dress keeping in view local cultural values… The purpose of the dress code… is to maintain good morale, respect, cultural values.”

It also goes onto say that “gaudy or immodest dress” is not permitted in classrooms, the cafeteria and university offices.

However, terms such as ‘dignity’, ‘decent’, ‘cultural values’ (mentioned twice), ‘good morale’ and ‘respect’ are highly subjective and ambiguous. What is decent for one may not be decent for another. So who decides what is ‘decent’?

Iqra University

The university asks its female students to wear “culturally suitable outfits”, raising the question of why male students are encouraged ─ even ordered to wear ─ western clothes instead of “culturally suitable” outfits (given the socio-cultural connotations behind the phrase).

Also read: At Pakistani universities, fear rules supreme on Valentine’s Day

Hyderabad’s Isra University

Here, an undertaking is signed between female students and the administration that binds the former to wear headscarves. Although the rule is enforced sporadically, it is there for any teacher to implement.

A female student at Isra University who refused to give out her name narrates how her university enforces some students to sport a ‘headscarf’:

“We signed an undertaking that we shall wear the scarf and lab coats inside the premises. We were also provided the headscarf and coat for free. But only our computer teacher forces us to wear both those items in our lab classes. It is never strictly imposed though, unless you are studying medicine,” she revealed.

A male ex-student from Isra University, Rafay*, looks beyond the moral undertones of the university’s arbitrary headscarf policy and feels that the administration should not have policies that it doesn’t seek to enforce.

“The university has made these codes but they don’t enforce them. There is no point in having these codes because they are only enforced selectively by teachers who are motivated on their own to enforce what they feel looks ‘decent’ on students.”

Why implement these dress codes?

An environment conducive to the development of free and independent thought is one of the cornerstones of a meaningful university experience. But in an attempt to regulate and moderate the physical appearance of its students, universities are undermining their own role as incubators for free thinking, progressive minds.

When students graduate from schools to universities, they are met with a number of changes. For one, there is no uniform. However, they must enter “the professional world” ─ an office environment in which workers are expected to dress a certain way.

This is the framework within which most universities try to rationalize their policing of attire.

Bahria University Spokesperson Mahwish Karman says the idea behind the institution’s dress code policy is to instill discipline among students, uphold the decorum of the institution and to follow societal and cultural norms of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan.

“Shalwar Kameez is restricted to Fridays because we have students coming from parts of KP and Sindh and they must be taught the proper attire for a business environment which does not include Shalwar Kameez,” she states, adding: “Similarly, for women Shalwar Kameez with dupatta is the appropriate attire.”

NUST, in its dress code policy, states that the purpose of the dress code “is to provide basic guidelines for appropriate work dress that promotes a positive image of NUST, besides allowing flexibility to maintain good morale, respect, cultural values and due consideration for safety while working at laboratories.”

Amidst the ambiguity, Amna Zaman, a student at NUST’s social sciences school points out that the idea to regulate what students wear is not as destructive as it is often made out to be.

“In our freshman year, we were asked to not wear jeans and I spoke to the Dean about it. He said ‘when you get into the business world, you can’t go to an office wearing jeans and a shirt’. The discrimination wasn’t just against girls, it was against guys as well,” Zaman says.

“It is not a very big issue for us, especially at the social sciences school. The rules are put in place to make sure nobody dresses too shabbily,” she explains.

“Personally I feel that they’ve tried to teach us to dress in a manner that is in line with the industry; you need to look presentable, you need to look more formal, whether you’re in eastern clothes or western clothes. I think that’s necessary. If I had my own university, I would enforce that too. Universities are not just about teaching people what’s written in the books. It’s also about training you for the real world.”

Karachi University, 1969-70

Nazli, who attended the Department of International Relations at KU in the late 60s, recalls there being no formal dress code in place.

“There was no dress code, but people would wear black cotton gowns similar to those worn by university graduates as part of a uniform. Everyone wore them. It was understood they would wear them.”

“I don’t remember a lot of girls wearing hijab. Sometimes girls would cover their heads with dupattas outdoors to protect themselves from the sun. Maybe about 10-20 per cent of the female students would wear hijab,” she says ─ a proportion that has grown exponentially since then, according to students who have attended KU in recent years.

“I mostly remember wearing shalwar kameez, but I think bell bottoms were in fashion then,” Nazli adds.

When it came to ensuring students were dressed ‘appropriately’, a proctor was responsible for taking disciplinary action against boys and girls who were not ‘decently’ dressed, she explains.

Punjab University, mid-70s

“Back when I was at the Punjab University (PU), there was no concept of a ‘dress code’,” reveals Shahida Sipra, a philosophy student at PU who graduated in 1977.

“We would sometimes ride our bicycles from Lahore’s main market to our campus wearing jeans and a top; nobody would object. Even on campus, there was practically no fear when it came to interacting with boys or wearing whatever you were wearing,” remembers Sipra, who is now a teacher.

Sipra’s memories of her time at university are reminiscent of an era when Islam was not as politicized as it seems to have now become ─ especially on campuses. “It all went downhill as Zia-ul-Haq came to power. The Jamiat propped up in Punjab University, bringing with it, a wave of conservatism and fear.”

“Girls would often get rid of their headscarves after moving to Lahore from smaller cities. For us, it was a way of identifying girls who were new to the city,” Sipra says.

Quaid-i-Azam University, early 80s

The Director of the Centre of Excellence in Gender Studies at Islamabad’s Quaid-i-Azam University, Farzana Bari has been affiliated with the university since the early eighties when she was a student here.

The culture of the university, she says, has changed a lot over the years, becoming more and more conservative.

“Then there was free mixing between students, and girls and boys treated one another as friends. Now most women cover their heads and many choose to hang around in women only groups,” she said.