By P.K.Balachandran/Ceylon Today

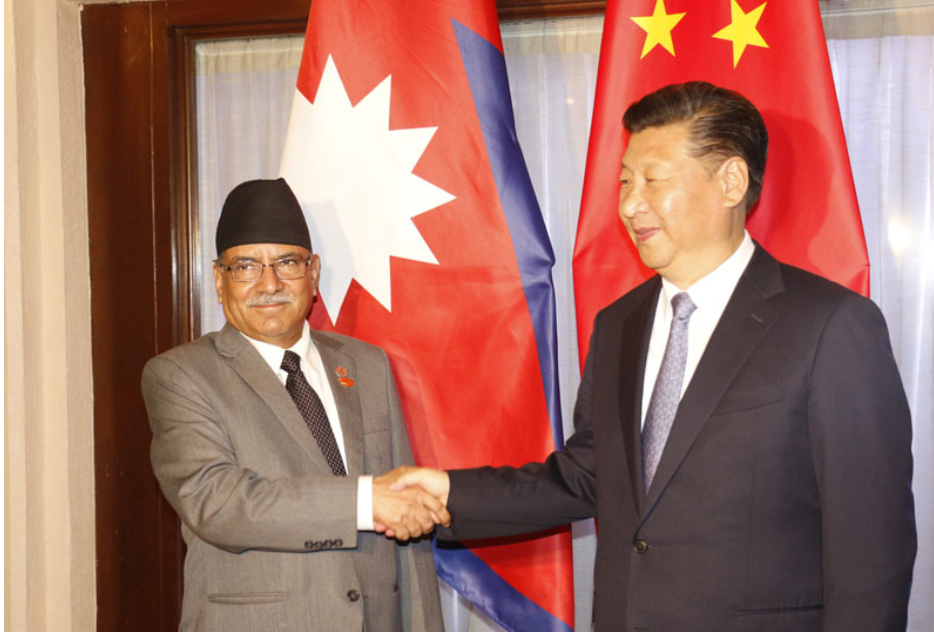

Colombo, July 3: Early in June, Nepal’s Prime Minister Pushpa Kamal Dahal visited India for four days, amidst a feeling in both countries that bilateral relations were none too good. The opinion in India was that Dahal should have called on the leaders in Delhi soon after assuming power in December 2022. New Delhi was also wary about the Maoist communist party leader’s potential to become pro-China.

In Nepal itself, Dahal was facing a vociferous opposition that had been pressing him to buttonhole his Indian counterpart, Narendra Modi, on unresolved issues such as trade in power, air corridors and territorial claims.

However, Dahal raised no contentious issue in his parleys with Modi and went along with the concessions and projects India offered, realizing that heightened conflicts with a powerful India would be detrimental to Nepal’s long-term interests.

At the same time, Dahal could not be dismissive about the China factor. Over the last decade, China has acquired a firm foothold in Nepal, facilitated by successive Nepalese governments’ interest in cultivating China as a counterweight to India. Close and helpful though it might be in many ways, India could be quite overbearing at times.

China Visit

To keep the China link active, Dahal is now be visiting China in September. “My India visit was highly successful and I can claim that my China visit will also be very successful. After China, I will visit the US to participate in the United Nations General Assembly and there is a possibility of meeting some US leaders as well,” the prime minister told Kantipur TV.

When Dahal was in New Delhi, his close confidant, Agni Prasad Sapkota, was in China. On his return, Sapkota told said that he conveyed to Beijing Dahal’s willingness to visit China at the earliest. Earlier, China had invited Dahal to participate in the Boao Forum for Asia held in March 2023, but he skipped the event because he was planning to visit India first.

Though heading the Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist Center) Dahal is now seeking a ‘balanced relationship’ vis-a-vis India and China. But in the past, he had flitted between “pro-India” and “pro-China” postures.

He signed the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), agreement with China when he was PM in 2017, ignoring India’s displeasure. In the forthcoming trip, Dahal hopes to convince Beijing to develop the BRI projects with grants rather than loans because Nepal has no means to repay loans.

Just as he was under pressure to take a a tough nationalist stand in his talks with India, Dahal is now under pressure from the dominant pro-China lobby in his own party, to wrest concessions from Beijing including a territorial issue (China has walked into some areas close to the northern border). But Dahal is highly unlikely to raise the territorial issue and irk the Chinese.

He is also unlikely to pledge support for China’s Global Security Initiative (GSI), because India and the US will frown on Nepal if it joins a China-dominated security plan. India, especially, will be cross because it considers itself as the “security provider” for the South Asian region.

Growing Chinese Footprint

After the 2005 Royal takeover of the government in Nepal, India, the US and the UK suspended military aid to Nepal, demanding the restoration of democracy. This paved the way for greater and stronger Nepal-China military ties. China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) started cultivating relations with Nepal’s defence ministers and army chiefs, a practice that continues to date, says the Nepalese daily Annapoorna Express.

In 1989, Nepal bought anti-aircraft guns, medium-range SSM, and AK-47 rifles from China—much to the chagrin of India, which maintained that the purchase went against the spirit of the 1950 India-Nepal Peace and Friendship Treaty. But India’s objections were in vain. In 2008, Nepal signed an agreement with China on military assistance worth U$ 2.6 million.

The 2015-2016 blockade of the Nepal-India border by Nepalese of Indian origin, who were fighting for their constitutional rights with covert Indian support, sent India-Nepal relations into a tailspin. As an inevitable consequence, Nepal-China ties got stronger. In 2017, Chinese Defense Minister and State Councilor Chang Wanquan came to Nepal and announced grant assistance of U$ 32.3 million. Nepal-China joint exercises were also held.

In 2020 Nepalese Foreign Minister Pradeep Gyawali sought a review of the 1947 Tripartite Agreement between India, the UK, and Nepal, which permitted India and Britain to recruit Gorkhas to their armies. Gyawali said that the agreement had “lost its relevance in the changed political context.” Nepal irked India by asking for the return of the Kalapani area also.

Nepal wanted to transform itself from a ‘land-locked country’ to a ‘land-linked’ country with the help of China. The Chinese Qinghai-Lhasa railway project had reached Zhangmu on the border with Nepal. Nepal and China planned to connect it to Kathmandu and then to Lumbini which is barely 30 km from the Indian border, writes Capt. Avinash Chhetry in the Centre for Land Warfare Studies (CLAWS) website, New Delhi.

“This will not only increase Nepal’s economic dependence on China but also the latter may use the strategic underpinnings of the connectivity corridors. This has the potential to threaten the northern plains of India,” Capt. Chhetry said.

Good relations with Nepal did not prevent China from occupying Nepalese territory. The Nepalese media cited a survey conducted by Nepal’s Ministry of Agriculture which claimed that there were illegal Chinese encroachments in bordering districts such as Gorkha, Dolakha, Darchula, Sindhupalchowk, Sankhuwasabha, Rasuwa and Humla, Chhetry pointed out.

“China’s encroachment into Nepalese territory in areas closer to Indian states of Uttarakhand and Sikkim, which are at high altitude, may give China an opportunity to ascertain certain locations so that it is at a strategic height and can look deep into India and Nepal using effective surveillance resources. Both, the Indian and Nepalese Armies, need to be prepared for any such eventualities,” he warned..

In 2018, Nepal’s decision to withdraw from the first-ever Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC) military exercise held in India shocked New Delhi. The last-minute withdrawal was attributed to Beijing’s pressure. .

“Nepal’s efforts to look for an alternative to India and external actors like China has created considerable security concerns for India. India needs to act fast and take the help of the Indian Military to achieve its national interests. Thus, it becomes important to analyze the role of the Indian Military as an effective tool, at all levels, to get the desired objective of a purposeful partnership between India and Nepal,” Capt. Chhetry recommends.

In forging stronger India-Nepal military links the Gorkhas of Nepal can play a critical role, Capt. Chhetry says. The Gorkhas and the governments of India have had close relations since the first half of the 19th.Century. The Gorkhas helped the British crush the 1857 Indian revolt. Over 100,000 Gorkhas fought for the British during World War I and II. After India became independent, a tripartite agreement was signed between India, Nepal, and Britain to split the Gorkha regiments between the three countries.

Presently, there are more than 32,000 Nepalese in the seven Gorkha regiments of the Indian Army and around 1,22,000 pensioners are residing in Nepal.

“If we include their families on an average of four per family, it will account for around seven lakh Nepalese i.e. 2.5 percent of Nepal’s total population which is inherently a part of the Indian Army’s large family. This emotive connection is one of the biggest strengths of the Indian Army in Nepal. A sizeable number of 15,773 retired Assam Rifles personnel are also living in Nepal. They are looked after by the Assam Rifles Ex-Servicemen Welfare Association (ARESA),” Capt. Chhetry says.

To break this link, China allocated around 12.7 lakh Nepalese rupees to an NGO in Nepal to carry out a study on what motivates the Gorkhas to join the Indian Army, the officer points out.

Capt. Chhetry also warns that as Pakistan is already using Nepal as a cockpit for intrigues against India, there is a possibility of Sino-Pakistan collaboration in schemes inimical to India.

END