By PK Balachandran/Ceylon Today

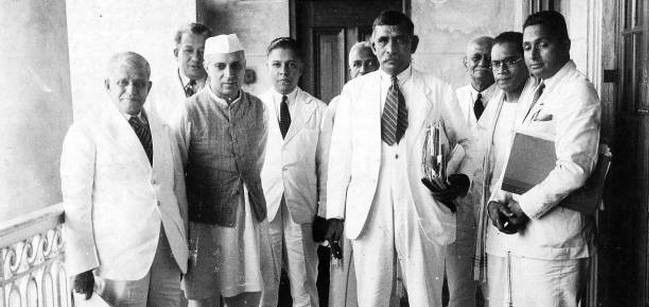

Colombo, November 22: Over a period of 30-odd years, spanning both the pre and post-independence periods, Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru tried to balance the interests of India and Ceylon on the question of the people of Indian origin in the island. The groundwork that he painstakingly did, helped subsequent Indian and Ceylonese Prime Ministers come to some agreements, albeit decades later.

According to Gopalkrishna Gandhi, author of Nehru and Sri Lanka (Sarvodaya Vishva Lekha Publication, Ratmalana, Sri Lanka, 2002), Nehru was pained, and at times angry, when he saw the hostility with which Ceylonese politicians in the 1930s and 1950s looked at Indian immigrant labor, completely disregarding the latter’s vital contribution to the prosperity of the island. In a message to the Natal Indian Congress in South Africa on June 5,1939, Nehru said: “Our cousins in Burma and Ceylon have turned against them (the people of Indian origin) and are pursuing an ill-conceived and narrow-minded policy which is sowing seeds of bitterness between them and India.”

According to The Ceylon Observer of June 22,1939, Nehru told the Sinhala Maha Sabha in Kandy, that while it would be an “absurd humbug” to say that Indians came to Ceylon purely out of goodwill, it could not be denied that they did “certain useful work and generally helped the processes of modern business to develop.” He pointed out that “large numbers” of them were required for the economy of Ceylon to function.

In 1954, after the bitter 13-year tussle with the Ceylon government over the issue of citizenship to the people of Indian origin who had been living in the island for generations, Nehru said: “Unfortunately, certain politicians and some groups in Ceylon neither speak nor act wisely, and repeatedly come in the way of friendly settlement. Even the last Indo-Ceylonese Agreement had some rough treatment in Ceylon and I am not sure how far it will be carried out.”

“It is not so much what is being done in Ceylon in regard to it, but the manner of doing it and the spirit behind it all, that has troubled me and that has irritated greatly the large numbers of people of Indian descent there,” Nehru said in a letter to the Chief Ministers of Indian states dated April 26, 1954.

“If these people lose all hope of fair treatment in Ceylon, then they may well take to wrong courses. They will suffer no doubt if they do that, but they can give a great deal of trouble to the Government of Ceylon. Because of this, apart from other reasons, the only wise course for the Government of Ceylon is to come to reasonable terms with them and with us (India),” he advised.

In 1949, when Independent Ceylon enacted the citizenship law, 659,0000 Indian settlers had applied for citizenship, but only 8,500 were included in the 1950 electoral register. In the previous register, there were 165,000 of them. Judgments of the Ceylon Supreme Court and the Privy Council had given 40,000 Indian settlers the right to Ceylon citizenship. But an amendment to the 1949 citizenship law made in 1952, said that only those families living in Ceylon since 1939 could be admitted. This affected thousands of Indians. About 900,000 Indian settlers, mostly estate and urban workers, were denied Ceylonese citizenship and voting rights.

There was a series of negotiations between the Indian and Ceylonese governments between 1941 and 1948, in which some broad principles were agreed upon. The conditions included a residence qualification; a means test; and compliance with Sri Lankan laws. Dual citizenship was ruled out. But the two sides differed in the interpretation of these conditions, and this rendered the agreement a dead letter.

Among the Indian origin people, the problematic category was those Indians who wanted Ceylon nationality on the basis of long years of residence, but who were denied that. Ceylon assumed that India would consider these Indian nationals and take them back. But Nehru said that no such assumption was warranted. Nehru’s policy in regard to overseas Indians was that they should deem themselves as people of their country of domicile and chalk out their destiny in those countries instead of looking to India.

He categorically told the Indian parliament on September 6, 1955: “The question basically is between the Ceylon government and these people. We come in because we are interested in these people. They are not our citizens. This we must remember.” They were residents and inhabitants of Ceylon “for generations” and, therefore, their status was a matter between them and the Ceylon government, he said.

Retrenchment

Prior to the controversy over citizenship, in 1939, there was the controversial retrenchment of 1,400 Indian daily wage employees in Ceylon government service, particularly at Colombo port. Nehru felt that since many of these workers had been living in Ceylon for 10, 15, 20 years or more, they should not be dismissed abruptly. There was a scheme for voluntary repatriation paid for by the government, but the catch was that if that was not availed of immediately, they would be retrenched next year, and that, without bonus.

On this Nehru said: “I did not ask the Ceylon government not to give preference to the Ceylonese in the matter of employment. But the question is the dismissal of those who are already there. I would expect any government to have labor laws to prevent it.”

Nehru was so angry at this, that he rejected an invitation from some leaders of Ceylon to visit the island to sort out the problem. Writing to his daughter Indira on this on July 3, 1939, he said: ” Two weeks ago I had an indirect and informal invitation from some ministers of the Ceylon government to go there. I sent a disdainful reply. If Indians were not good enough for Ceylon, Ceylon was not good enough for me.” Eventually, he did go, under pressure from his Congress party.

Ceylonese Sensitivities

Nehru was well aware that behind the problem of Indian labor was a “fear of the great land of India somehow overwhelming Ceylon, not by military might but by very numbers. Hence the excessive importance they attach to limiting the people of Indian descent or Indian sympathies.”

Nehru was acutely aware of the dangers of alienating the Ceylonese. In a letter to the Chief Ministers of Indian states dated July 5, 1952, Nehru said: “The Sinhalese look up to India as their holy land because of the Buddha. But they are a little afraid of this great big giant of a country overlooking them and fear always leads to wrong action. If we threaten them we only increase their fear. Therefore, I have avoided speaking the language of threats and have tried to be friendly to them even when they have acted in an improper way.”

In his letter to the Chief Ministers dated April 26, 1954, Nehru said: “We have always to remember this fear of the Ceylonese. Any so called pressure tactics on our part tend to increase this fear, and therefore, make the solution a little more difficult. They begin to look away from India in matters of trade etc. and rely on some distant country like England or, it may be, even Australia rather than India.”

However, Nehru believed that though the Ceylonese leaders were itching to throw the Indian estate laborers out, the people of Ceylon knew their worth.

“A day would come when the people in Ceylon would put up a monument to the tea estate laborers who had come from India and who had done so much for Ceylon,” he predicted.

END