By P.K.Balachandran/Sunday Observer

Colombo, January 7: Anagarika Dharmapala of Ceylon and Dr.B.R.Ambedkar of India were both Buddhist revivalists who made a profound difference to the socio-political life of their respective countries. But their goals were different.

The similarities and differences between the endeavours of Dharmapala and Ambedkar are succinctly brought out in a paper by the renowned Indian Buddhist and Pali scholar, the Late Prof. Balkrishna Govind Gokhale published by the Journal of Asian and African Studies in February 1999.

Dr. Gokhale, who was Professor Emeritus of History and Asian Studies at Wake Forest University, North Carolina, goes back to the roots of the thoughts of Dharmapala and Ambedkar and explains the similarities and differences in their approach to the objective conditions surrounding them.

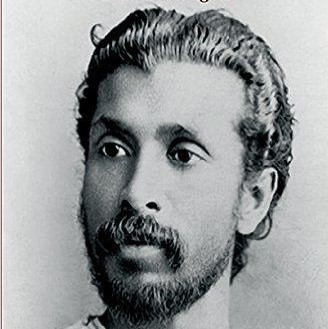

For both Dharmapala (1864-1933) and Ambedkar (1891-1956), Buddhism was a pathway to liberation from an oppressive system. In the case of Dharmapala, it was the hegemony of Christianity and Western culture in British-ruled Ceylon in the late 19 th,, and early 20 th.Centuries.In the case of Ambedkar, it was the oppressive and intolerant caste system in India.

The search for modernization and a reaffirmation of religious identity were two powerful forces in the making of 20 th., Century India and Ceylon. The idea of nationalism and aspirations for social and economic transformation were among the most powerful aspects of the modernizing process in the two countries.

At that time, nationalism in India and Ceylon sought to reaffirm the validity of traditional religious/cultural world-views while accepting the need for changes in thinking based on modern knowledge to ensure economic progress and national independence.

Reaffirmation and reform were seen as two sides of the same coin or, as Prof. Gokhale put it, “parts of a symbiotic process.”

Intensification of Christian missionary activity in Ceylon towards the end of the 19 th.Century, opened up the disturbing possibility of the indigenous population losing faith in their traditional religions. In the past, these religions had been a badge of identity and a source of pride. People were in danger of losing the badge of honour, as it were.

The indigenous elite felt the pinch more than the hoi polloi although they were beneficiaries of the new institutions created by the British-Christian government. They felt that the new challenge had to be met and that through a combination of reform of, as well as a revival of Buddhism.

Prof. Gokhale points out that the movement in India led by Raja Ram Mohan Roy (1772-1833) was both an effort towards reform as well as a reaffirmation of Hinduism. The Theosophical movement (in its eclectic outreach) helped this reaffirmation. In Ceylon, the public recitation of the Tisarana (the threefold refuge in the Buddha, Dhamma and Sangha) and the Panchasila (five precepts for Buddhist lay men and women) by Madame Blavatsky (1831-1891) and Colonel H.S. Olcott (1832-1907) on May 21, 1880 inspired a Buddhist revival.

Reform and revival movements loosely linked to an incipient nationalist movement played a significant role in the social and political history of the times. All major religions of India and Ceylon were part of the awakening and all happened around 1875.

Around this period, the Hindu elite of India came under sway of the Theosophical movement and the Arya Samaj. Muslims came under the Aligarh educational movement. In Ceylon, Dharmapala, and later the Temperance Movement, awakened the Buddhists. Ceylon Tamils were stirred by the Saivite movement led by Arumuga Navalar. Muslims were influenced by the reformist advice of Arabi Pasha, an Egyptian exile.

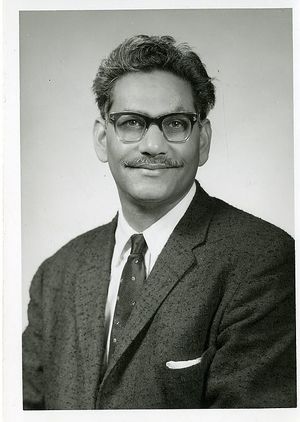

While the revivalist movements were catching up among the Indian elites (who were English-educated and belonging to the upper castes), there arose a parallel and contradictory movement of the lowest castes then officially dubbed as “Untouchables”. The latter was led by a highly educated lawyer and economist Dr.B.R.Ambedkar.

An “Untouchable” himself, Ambedkar awakened his community. He first fought for their political rights and then for social rights by drafting independent India’s constitution with affirmative action as one of the main pillars.

During India’s freedom struggle, the all-embracing Congress party led by Mahatma Gandhi, was focused more on driving the British out than on social reform, specifically reform of the caste system of which the worst victims were the Untouchables. Ambedkar stepped aside from the nationalist struggle against the British and concentrated on getting the Untouchables their basic rights.

Prof. Gokhale describes the clash between Ambedkar and Gandhi succinctly. In opposition to Gandhi, who wanted to keep the caste system while opposing untouchability, Ambedkar wanted to throw the caste system (a hierarchical system based on birth) lock, stock and barrel.

While Gandhi saw urbanisation and industrialization as inherently exploitative and violent and advocated a return to the villages, Ambedkar saw the Indian village as a cesspool of backwardness and caste bigotry. He believed that only an impersonal, industrialized, urban setting would enable economic and social mobility of the lowest castes.

In opposition to leaders of the Indian nationalist movement who wore the Indian attire as a mark of nationalism, Ambedkar was always in a Western suit. He urged his followers not to shun Western culture as it would be their avenue of mobility.

Despite his total opposition to Hinduism because of the caste-system, Ambedkar did not want to convert to a “non-Indic” religion like Christianity or Islam. From among the Indic religions he chose Buddhism because, in his view, Buddhism was not only anti-caste and but was very scientific and practical in its approach to the problems of humanity.

When he publicly converted to Buddhism in 1956, millions of Untouchables (called Harijan or Dalit after independence) followed suit. Today, Ambedkar is deified by the Dalits and his praise is sung by all parties because swearing by his principles is mandatory to get Dalit votes.

Like Ambedkar, Dharmapala also became a legend in the history of Simhalese nationalism. Like Ambedkar, Dharmapala was a modernizer, though he became a monk eventually. His other concern was the despicable condition of the places of Buddhist pilgrimage in India. He was pained to see Bodh Gaya in ruins and under the control of a Hindu priest. With the help of influential Westerners like Edwin Arnold (author of Light of Asia) and a section of the Bengali elite in Calcutta, Dharmapala saw to it that the temple was restored to the Buddhist. He formed Mahabodhi Society, a premier Buddhist institution in India.

Using a revived and reformed Buddhism as an instrument, Dharmapala made the Sinhalese staunch nationalists, very proud of their country and religion.

This is what Prof. Gokhale says of Dharmapala: “He made Buddhism self-confident as an instrument for the reaffirmation of the Simhalese cultural identity for elites as well as masses. He worked for a Buddhism that had to be different from the old reclusive creed innured in the cloistered recesses of monasteries. It had to be bold in its reinterpretations of social, economic and political agendas though loyal to the demands of the Vinaya, Sutta and Abhidhamma heritage. His Buddhism was to be a new Protestant creed, as called by some modern scholars but, as Dhammapala (Dhramapala) insisted, pristine in the integrity of its message for a modern Sri Lanka.”

“This revived and reaffirmed Buddhism was based on the innate rationality of the original message, scientific in its orientation and humanistic in its morality concerned with the demands of the here and now. It had faith in man as an architect of his own destiny. It may be centuries old in its chronological age but was perennially modern in its acceptance of the scientific spirit and demands of technological change. This Buddhism, Dhammapala felt, could be the vehicle for its new pilgrimage into a modern world of economic progress and political independence.”

END