By I.A.Rahman/Dawn

To the people of the older generation in Pakistan and India, the present level of confrontation between their countries, especially the war of words between their media persons, sounds like a steep fall from the standards of mutual understanding and decency with which they used to treat one another not long ago.

There were wars between the two countries that did not rob the soldiers of respect for each other’s interest or dignity. We had a full-scale conflict in 1965, but there was no rupture in diplomatic relations. While tanks collided with tanks, soldiers in rival camps recognised each other as normal human beings and many of them treasured memories of days of comradeship.

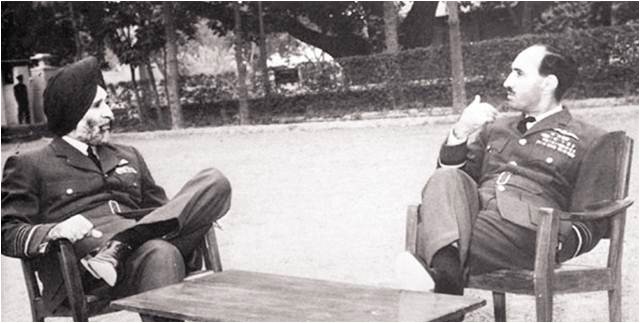

The Pakistan Air Force chief, Air Marshal Nur Khan, had no doubt wished his men “happy hunting”, but he was at the same time reported to have secured an understanding with his Indian counterpart that each other’s industrial and civilian assets would not be targeted.

This gentlemanly code of warfare was considerably eroded by the time the 1971 conflict broke out. Even then, after the surrender at Dhaka, an Indian brigadier sought out a Pakistani brigadier he had known, took him to his tent for a drink and said: “What have you done?” More than a tone of victory, or even reproach, these four words conveyed a feeling of sadness felt by a warrior at the plight of a fellow warrior.

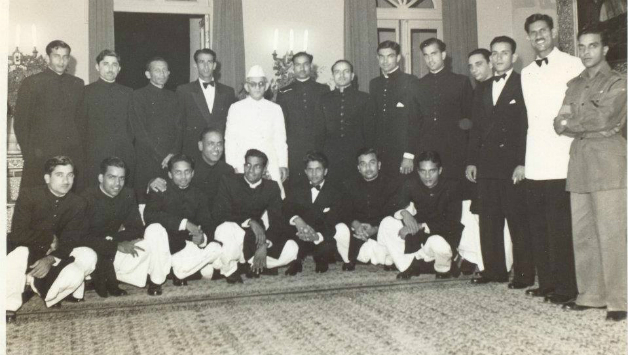

Today Pakistani poets, actors and sportsmen are being hounded by Indian gangs. Can we ever forget the warmth and goodwill Pakistani poets received from India’s political, social and business elite when they went to Delhi to attend mushairas organised by a millowner who had suffered heavily at the time of partition. And this was barely eight or nine years after the bitterness of partition.

Or the competition between Indian immigration staff when they noticed Ghulam Ali in the queue at New Delhi airport? How Nusrat Fateh Ali touched the hearts of India’s music lovers reminds one of the homage paid by Tamil Nadu pundits to Roshan Ara Begum by describing her as an incarnation of Saraswati. The way Abida Parveen won the hearts of a big crowd at the Connaught Place is recent history.

As for sports, Raja Ghazanfar Ali persuaded the governments of India and Pakistan in the mid-fifties to allow a large number of Pakistanis to watch a cricket match between the two countries in Amritsar. Many Lahori young men, including journalists, were able to enjoy hospitality at the houses of Sikh strangers they decided to knock at.

How can one forget the fact that many Indians cheered Pakistan when they faced England in the 1992 World Cup final or when both Indians and Pakistanis cheered Sri Lanka during the final against Australia in the 1996 World Cup. There was a sense of attachment to the people next door that could survive all irritants.

Today an Indian is prosecuted for cheering a Pakistani team and a Pakistani boy is sent to prison for applauding Virat Kohli.

This change has not come suddenly. The state agencies have worked energetically for it and media has made the mistake of playing along.

The newspaper editors of India and Pakistan had laid the basis of friendship between them while the first war in Kashmir had not really ended. A tradition of looking at things unaffected by the state narrative of confrontation grew.

After the 1971 crisis the journalists of India rushed to understand what the new Pakistan was. One can recall a steady stream of media persons coming to Pakistan – from Dilip Mukherjee and Nihal Singh, to Rajinder Sarin and Pran Chopra. Their patriotism did not prevent them from befriending Pakistan.

Later on Shyam Lal, B.G. Verghese, Kuldip Nayar, Shekhar Gupta, Bhardawaj and Barkha Dutt found it possible to interact with their Pakistani counterparts. When the Bharatiya Janata Party started getting the better of Congress a good number of Pakistani journalists rushed to hear from Vajpayee, Advani and Jaswant Singh what the change signified.

These interactions contributed considerably to non-government efforts to promote peace in the region. Peace activists from both countries were able to meet in Lahore in 1994 and adopt agreed positions on issues over which the two governments are today trying to tear each other apart.

And let us not forget that the call for an “uninterrupted, uninterruptible dialogue” between India and Pakistan was raised from the platform of a regional media association.

Media jingoism

What has gone wrong? The rise of politics of exclusion in both countries is a significant factor. The electronic media’s decision to carry the Kargil conflict into the homes of Indian and Pakistani citizens did a good deal of mischief. The media failed to respect the line that separates nationalism from humanism.

From then on, the media on either side has been losing its capacity to respect the other side’s history and interest of the masses. It gloats over the destructive powers of its military and ignores the failure of the two states to feed, clothe and educate nearly half of their populations.

The latest US appeal to India and Pakistan to stop hostile propaganda against one another is an echo of a key provision of the Tashkent Accord (1966) and similar clauses in other bilateral agreements, including the Liaquat-Nehru pact. Unfortunately these agreements to do away with invective have been honoured more in breach than in compliance.

It is time the Indian and Pakistani media realised the great harm to the people of the Sub-continent caused by their war of words, completely oblivious of the fact that the wounds caused by words take longer to heal than the wounds made by swords.

The consequences of an unbridled use of hate material to influence the outcome of a political disagreement or dispute should easily be visible to everyone. The first casualty is the media persons’ faculty to separate fact from propaganda. Whatever is churned out by the propaganda mills of insecurity-driven state authorities is accepted as the gospel truth and used as the foundation of arguments that push the contending parties further and further away from mutual understanding and reconciliation.

The result is that the media loses its capacity to test the truth in one’s national narrative and to recognise the truth in the adversary’s narrative.

We can recall the tactics used by the Second World War belligerents to demonize the other. One big power chose to describe the troops of an adversary as rats and its own war objective as a holy campaign to save the world from ‘yellow peril’.

Some of these practices spilled over into accounts of anti-colonial struggles. When the Vietnamese were labeled as Viet Cong they ceased to be normal human beings and when the Algerian freedom fighters were identified as “Moslem terrorists” they lost in the eyes of the European public all of their human entitlements.

The world did learn to respect the inherent dignity of parties to a confrontation. At the height of the Cold War, Ronald Reagan could not go beyond characterizing the Soviet system as evil and stopped short of attacking the dignity of Soviet citizens. Now the Indian and Pakistani journalists, especially in the electronic media, seem determined to make efforts to demonize the other to unprecedented, and palpably abused, heights.

They are not content with attacking the policies and conduct of the rival state; they are forever looking for the choicest words of abuse for not only the other’s rulers but also for the entire people.

Unfortunately the consequences of these hate campaigns are not realized. These practices often harm their authors more than the targets of their venom. Any people driven by hate lose the capacity to think straight and appreciate matters in a proper perspective.

They thus descend from reasonable behavior into the abyss of irrationality. The media mercenaries seem to be out to convert India-Pakistan differences into permanent hostility, an endless saga of mutually destructive conflict.

Previously the people of the Sub-continent were driven by their governments into confrontationist postures; now the media is filling hearts and minds with so much of hate and intolerance that they would not easily let the state leaders move from confrontation to reconciliation.

No greater disservice to the unfortunate people of India and Pakistan is possible.

Modern states are becoming less and less amenable to public opinion. The media alone cannot determine what the states should do, but the world will be a much poorer place for everyone if it surrendered its right to tell them what they should not do.

END