By P.K.Balachandran/Sunday Observer

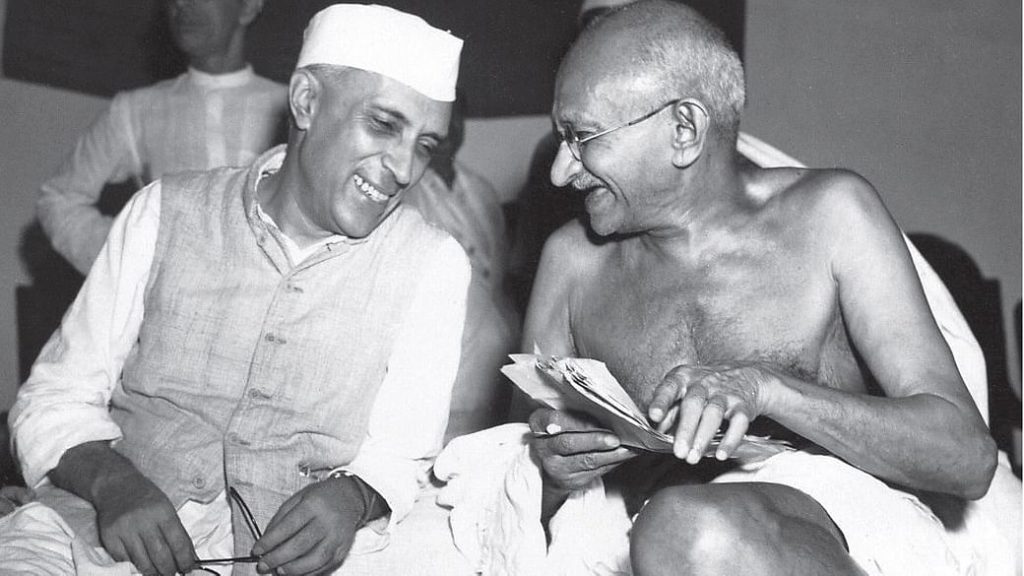

Colombo, November 24: Cambridge University historian Yasmin Khan describes how India’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru tackled a national crisis of gigantic proportions created by the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi within months of gaining independence, and how the funeral and mourning were designed by him to build a united and secular “Nehruvian” India.

By P.K.Balachandran/Sunday Observer

Colombo, November 24: The assassination of Mahatma Gandhi by a Hindu fanatic on January 31, 1948 in New Delhi, though immeasurably unsettling, played a seminal role in uniting a conflict-ridden India both emotionally and politically, says Cambridge University historian Prof. Yasmin Khan in her paper in Modern Asian Studies (Vol 45, Issue 1, Jan. 2011).

The elaborate State funeral and the 14-day nation-wide memorialization which followed, played a seminal role in giving newly independent India a firm foundation marked by unity and secularism, that was the need of the hour after the partition of India in 1947 that was marked by mass killings and mass migration between India and Pakistan.

India’s first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru thoughtfully used the assassination of the Father of the Nation to build India after his heart as well as strengthen the new born Indian State and legitimize the leadership of the Congress party, says Prof. Khan.

She shows how the Congress government headed by Jawaharlal Nehru managed to mitigate the high voltage Hindu-Muslim tension that gripped the newly independent country following the assassination of the much revered Gandhi.

As India faced the prospect of another carnage, Nehru, backed by Governor General Lord Mountbatten, planned a grand State (military) funeral and a 14-day memorialization programme with three objectives: (1) bring out the innate mass appeal of Gandhi’s philosophy based on non-violence and communal harmony; (2) legitimise the new government; (3) and strengthen secularism and its votary, the Congress party.

The assassination revived the cult of Gandhi that was waning in the final years of the British Raj. From 1946 on, Gandhi was no longer at the centre of decision-making in the Congress because his opposition to partition on the basis of religion seemed to be utopian. He was also misunderstood by Hindu and Muslim extremists, with the Hindus branding him a lackey of the Muslims and the Muslims seeing him as a covert agent of the Hindus.

But his assassination at the hands of Hindu extremist, Nathuram Vinayak Godse, brought into the open the huge reservoir of public support Gandhi really enjoyed, totally disproportionate to the then image of him as an out-of-date politician.

Given the creation of Pakistan only a year earlier, Hindus at first thought that the assassin was a Muslim and an anti-Muslim pogrom seemed imminent. But the Nehru government strained every nerve to disabuse Hindus of the dangerous notion. Melville de Mellow and other announcers of All India Radio repeatedly broadcast that the alleged assassin was a “Hindu fanatic, not a Muslim”. This brought the searing communal temperature down dramatically.

Public outpourings of grief were of epic proportions, says Prof. Khan. It seemed that what the apostle of peace and Hindu-Muslim harmony could not achieve in his lifetime, he did upon his violent death. Of course as a precautionary measure the government banned the Hindu Rashtra Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and arrested over thousands of them. It also banned the Muslim National Guards and the Khaksars.

Importantly, Nehru used the communal calm to speed up the drafting of a secular and democratic Indian constitution, finalising it by 1949 and putting it into effect in January 1950 within two years of Gandhi’s assassination.

Marrying Modernism with Tradition

Acutely aware that in a country as rooted in tradition as India is, the pomp and show of Gandhi’s funeral was a mix of State pageantry and traditional Hindu funeral rituals. Nehru was aware that independent India will have to be both a powerful State and one shaped by tradition. The funeral and the mourning exhibited both aspects.

The bier was not carried by kinsmen as is the Hindu practice, but placed on a converted gun carriage. The “militarism” of the funeral was also striking. According to Prof. Khan 4000 troops, 1,000 armed men, 100 police and 100 navy men marched in the funeral procession. These were drawn from units of the Indian army like the Rajputana Rifles, Madras Regiment, Bengal Sappers and Miners, Indian Signal Corps, armoured vehicles and the mounted cavalry of the General-Governor’s Body Guard. The gun carriage was pulled by troops, with relatives and other disciples on foot in front of it.

“Baldev Singh (Defence Minister), Nehru and Sardar Patel (Home Minister) were seated alongside the body on the main vehicle itself, with Gandhi’s son, Devdas Gandhi, as the chief mourner, seated at the head of the vehicle. The kinship of the leading Congressmen with Gandhi was therefore visibly emphasized with Nehru naturally assuming the role of ‘son and heir’, Prof. Khan notes.

Through the procession, the Indian State had made Gandhi its totem and also legitimising the leadership of Gandhi’s declared heir, Jawaharlal Nehru. And backing Nehru was his friend in the British Raj, Governor General Lord Mounbatten. According to Khan, Mountbatten was the hidden hand behind the planning of the Statist pageantry of the funeral procession. In fact, the funeral procession was commanded by the British Indian army chief, Gen. Sir Roy Bucher.

However, at the cremation ground Raj Ghat, all the trappings of the modern State fell off and traditional Hindu rites took over. Gandhi’s son, Ramdas Gandhi performed the lighting of the pyre as the attending priest, Pandit Ram Dhan Sharma, recited Vedic texts.

People frantically picked up relics of Gandhi for preservation. “There was a great scramble and a diligent search for small twigs of the sandal chips near the pyre and many were seen, with the greatest reverence, picking up withered and trodden rose petals, picking up twigs from the mound of wreaths or bits of ash blown by the breeze,” Prof Khan writes.

Most significantly, the fortnight of national mourning declared by the Congress leadership coincided with the holding of the Ardh Kumbh Mela at Allahabad, or Prayag, at the confluence of three rivers Ganga, Yamuna and Saraswati, which is held every six years and at which thousands of sadhus, and pilgrims gather for a mass ritual bathing, for the cleansing of past sins.

At the Ardh Kumbh Mela, thousands of pilgrims prayed in front of a large portrait of the Mahatma which had been placed on a dais with a Charkha (spinning wheel) in front of it, and the Quran and the Gita on either side of it. The dais had become a temple with many offering coins as is done in temples to various Hindu deities. The Gandhi cult had become part of folk Hinduism.

Distribution of Gandhi’s Ashes

Gandhi’s ashes were immersed in the confluence of the rivers Ganga, Yamuna and Saraswati at Allahabad as per custom. And significantly, the ashes were taken to every State in India to be immersed in the local holy river. They were also taken to Hyderabad and Rampur in North India, which saw communal riots during the partition. Here too the ashes were reverentially accepted and immersed in the local waters solemnly underscoring the healing of communal wounds.

The parcelling out of the ashes to all States of India played a role in linking reverence for Gandhi to the authority of the Congress and the new Indian State. Condolence meetings were held in mosques, churches, temples, educational institutions, bar associations and Congress committees..

Prof.Khan points out that these moments were utilized to square conflicts and provided an extraordinary outlet for reconciliation which would otherwise have been unavailable. Giving an instance of accommodation following a conflict, a disputed plot of land contested by Hindus and Muslims in Bangla Bazaar, a suburb of Lucknow, was dedicated as a space to raise a memorial to Gandhi instead.

END