By P.K.Balachandran/Daily Express

Colombo, February 4: The movement for greater participation in government, which marked Ceylonese politics in the 1930s, became a movement for independence in the 1940s, thanks, in a large part, to World War II and political developments in neighboring India at that time.

The Ceylonese quest for Dominion Status within the British Commonwealth followed events in where the Congress Party led by Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru had decided, even at the outbreak of hostilities in Europe in 1939, that India must seize the opportunity thrown up by the war to press for full freedom.

The Congress made cooperation in the war against Fascism, Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan, subject to Britain giving independence to India.

The goal of full Indian independence (Purna Swaraj), enunciated by the Congress in 1929, appeared to be within reach in 1939. By 1940-42, the war had enveloped the whole of Europe and East and South East Asia with the British and their allies in retreat everywhere, boosting the confidence of anti-British forces in India.

On the grounds that India was dragged into the global conflict by the British without consulting its representative leaders, the Congress announced total opposition to the war effort unless the British gave full independence immediately.

This worried the wartime coalition government in Britain headed by Winston Churchill. India was a major source of food, raw material and manpower for the Allied forces. By the end of the war in 1945, two million Indians were in uniform and fighting all over Europe, South East Asia and North Africa. Furthermore, the British had been economically exploiting India for decades before that, by making India pay for British troops. The terms of trade between India and Britain were completely in favor the imperial power.

Therefore, the powers-that-be in London feared that these advantages would be lost if Britain did not win the war. And the war effort would be grievously impaired if the rebellious Indian leaders were not coaxed into supporting it.

The mission to coax the Indian leaders was entrusted to Sir Stafford Cripps, Leader of the House of Commons. Cripps arrived in India in March 1942 and offered Dominion Status to India on par with Canada, Australia and South Africa, after the successful conclusion of the war.

But the Congress rejected the offer and sought full independence as a condition for cooperation. The Cripps Mission failed.

Impact on Ceylon

However, Cripps’ offer of Dominion Status to a non-White part of the Empire like India, had its impact on Ceylon, whose nationalistic leaders latched on to the Dominion Status demand with alacrity.

They too were aware that Ceylon was playing a hugely important role in the war in South East Asia. Ceylon had become a major Allied logistic hub. The headquarters of the South East Asia Command (SEAC) under Lord Louis Mountbatten was located in Peradeniya. Its ports and numerous new airports played a great strategic role. Its rubber was invaluable.

The British too realized that the Ceylonese leaders had to be placated to enhance their cooperation. The Commander-in-Chief of the Allied forces in Ceylon, Adm. Geoffrey Layton and Governor Sir Andrew Caldecott, strongly felt that Ceylonese leaders would have to be co-opted by promising greater powers after the war. Even the tough, unyielding and often rude Adm.Layton felt that Britain would have reshape its relations with its colonies after the war.

But unlike in India, and fortunately for the British, the Ceylonese leaders had already chosen to cooperate as part of their strategy of coaxing the British to yield to their demands after the war. Unlike their counterparts in India, the Ceylonese leaders were convinced that Britain and the Allies would eventually defeat the Axis powers.

Don Stephen Senanayake (D.S.Senanayake) and other top leaders became part of the War Council headed by the Governor Sir Andrew Caldecott. And the cooperation was full, despite the abrasive and abusive conduct of the all-powerful Commander-in-Chief Adm. Layton.

1943 Declaration

On May 26, 1943, the British government issued a Declaration on Ceylon. It envisaged a Westminster model of government and full independence in internal civil affairs. The Crown (the British Governor) would retain Defense and External Affairs. It also stipulated that the constitution would have to be approved by a three-fourths majority ( 48 out of the 53 members) in the State Council. The last provision was inserted to ensure that minorities like Tamils, Muslims and Indian Tamils, were not road rolled into submission by the majority Sinhalese.

The Board of Ministers was asked to draft a constitution. The challenge was accepted by D.S.Senanayake. His draft did not accept the vociferous Tamil demand for communal representation. But it envisaged a Second Chamber (Senate) to give representation to the minorities and other interest groups. As a further safeguard against communal discrimination it envisaged independent Public Service and Judicial Commissions.

Instead of accepting the draft constitution as promised, the British government sent a three-man commission under Viscount Soulbury in 1944. Disappointed, D.S.Senanayake and other members of the Board of Ministers refused to officially depose before the commission though privately they briefed its members. The minorities deposed, but Senanayake did not mind as he felt that they had the right to be heard.

However, with the consent of Senanayake, S.W.R.D.Bandaranaike moved in the State Council , the Ceylon (Constitution) Bill, also known as “Sri Lanka Bill of 1945”. It included a Second Chamber (Senate) to safeguard minority interests. This was passed by the State Council with 40 votes for and 7 against.

Eventually, a compromise was worked out with the involvement of Lord Louis Mountbatten and others. The Senanayake-drafted constitution (which included a Second Chamber) was approved by the Soulbury Commission almost in toto. It is rightly said that the so-called Soulbury constitution was actually “D.S.Senanayake constitution” drafted by the constitutional expert Sir Ivor Jennings.

Minority Safeguards

Subsequently, the Senanayake draft was approved by the State Council by 51 votes for with only 3 against. This showed that the minorities were largely for it, Senanayake contended.

In his speech at the State Council, Senanayake said: “ We devised a scheme which gave heavy weight to the minorities. We deliberately protected them against discriminatory legislation. We vested important powers in the Governor General because we thought that the minorities would regard him as impartial. We decided upon an independent Public Service Commission so as to give an assurance that there should be no communalism in the public service. All these have been accepted by the Soulbury Commission and quoted by them as devices to protect the minorities. The accusation of Sinhalese domination has thus been shown to be false.”

“We are for one another, whatever our race or creed. Accusations of rabid communalism were no doubt inevitable, but they hurt because they seemed to us to be manifestly untrue. The recommendations of the Soulbury Commission show that in the opinion of three eminent and disinterested persons from outside, they were untrue.”

Dominion Status

Referring to the British government’s White Paper of October 31, 1945, Senanayake said, that though Dominion Status had not been granted, it did say that Dominion Status might be attained in a “comparatively short time”. He would say that if bread was offered instead of the promised cake, it should still be accepted and not rejected outright. Senanayake was practical.

His contention regarding Dominion Status was that the new constitution had all provisions which would be found in the constitution of a Dominion in the British Commonwealth.

Writing on the subject, Ranil Wickremesinghe said: “The Soulbury Constitution saw eight amendments made to it, the last being in 1971, when Act No. 36 of 1971 abolished the Senate, the instrument proposed by Hon. S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike, and adopted by Lord Soulbury to introduce checks and balances to the fledgling democracy of Ceylon in 1947.”

Curtains came down on the Soulbury constitution in 1972 when the government headed by Mrs.Sirima Bandaranaike replaced it with a Republican Constitution cutting all links with Britain other than the membership of the new Commonwealth of Nations with the British crown its titular head.

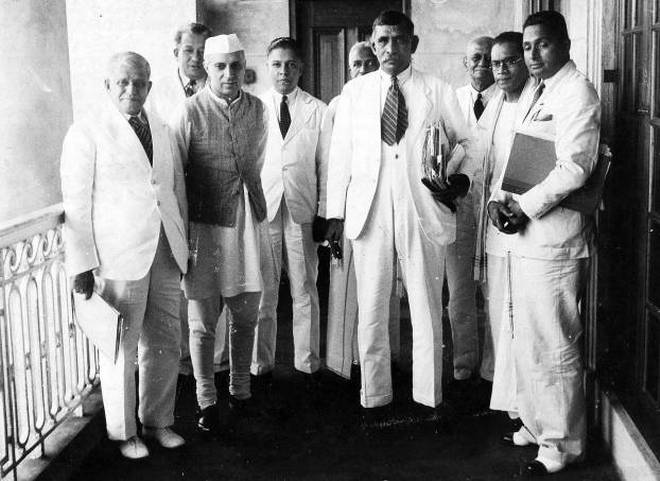

(The featured image at the top is that of the Father of the Sri Lankan nation, Don Stephen Senanayake)