May 25 (BBC) – In the past two weeks two global superpowers have had to face an unsettling reality – census results in the US and in China indicate that both countries are likely to start shrinking in population much sooner than they thought.

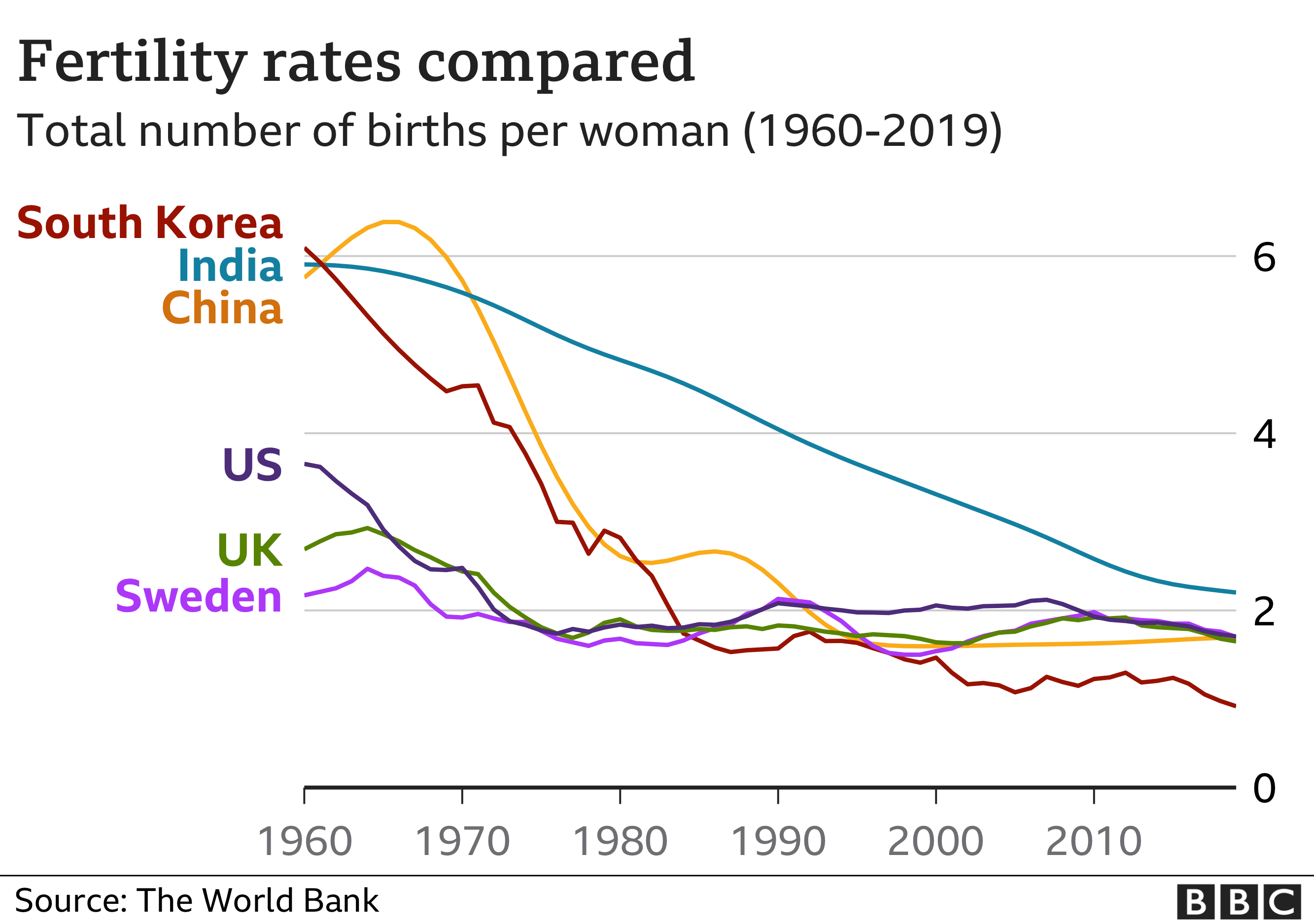

That’s because fertility rates are falling fast. As that happens, the population gets older, which can stand in the way of economic growth. It’s something governments are usually keen to avoid.

China and the US are not at that point yet. But they could learn from other countries that are already thinking about how to boost fertility.

It’s a thorny problem with no easy solutions. Some, like Russia, have tried throwing money at it, offering parents generous cash incentives to have children. But policies like this rarely work in a vacuum – parents need a system that offers much more. So, how can a government convince people to have babies?

1. Give parents affordable childcare

The small town of Nagi-cho is a happy outlier from Japan’s shrinking population. Over nine years it managed to double its birth rate – from 1.4 to 2.8 children per woman with an extensive scheme of family friendly policies.

Families get baby bonuses and children allowances but it also costs half the national average to send a child to nursery. Its success has been extraordinary but it’s a small, rural town. In the rest of East Asia, crippling work culture makes it difficult for mothers or fathers to balance the needs of work and family.

South Korea has one of the lowest fertility rates in the world and has spent more than $130bn (£92bn) on incentives for families. Some of these sound pretty obvious – free childcare, housing benefits or support for IVF. And some, like the holidays offered to civil servants so they can go home and make babies, are more creative. But none of them seem to be working.

Kim Ji-ye has a busy job in sales and marketing in Seoul. She had no interest in having a child but relented to pressure from her parents – her son is now three. Though she receives “infant support care” money from the government she doesn’t believe cash incentives made a difference to her decision.

Public childcare places in big cities are limited – some have years-long waiting lists – and private childcare is expensive.

“I never want to have another child,” she says. “It is just too hard to raise even one, so I just want to focus on him.” None of these government initiatives have managed to tackle a working culture across East Asia that tends to be hostile to family life.

“In Korea we have legal working hours and maternal and paternal leave policies,” says Erin Hye Won Kim, an assistant professor at the University of Seoul who studies fertility in the region. “But the take-up levels are really low, especially for paternal leave. It’s a matter of enforcement really.”

2. Make work more flexible

South Korea, China and Japan are extremes but in most developed countries work culture is in conflict with family life.

One option available to governments is to try to make part-time work more available. Countries with a higher prevalence of part-time positions do tend to have higher fertility rates. But more often than not it is women who take up these part-time roles. That inhibits gender equity and is not ideal for a country with an ageing population because it reduces the workforce even further.

It is possible to keep women in work and raise fertility. Sweden is often celebrated for its family friendly practices, not just in government but in business too.

“We have an understanding that during some part of their life women and men have small children and sometimes they have to go home early from work,” says Professor Gunnar Andersson, head of Stockholm University’s Demography Unit.

And there are other ways to make work flexible without reducing hours.

A study in 2017 showed that increased access to broadband in Germany correlated with higher birth rates in highly educated women. Working from home women found they could spend more time with their children and they choose to have more. The same effect wasn’t found in women with lower levels of education or with men.

A similar dynamic might be playing out in Finland now, says Prof Anna Rotkirch, who advises the Finnish government on fertility. The country bucked an overwhelming trend of falling birth rates last year by increasing its birth rate slightly during the pandemic.

Prof Rotkirch believes Finland’s education system had a part to play as it switched to online learning very smoothly.

But she also noticed something else – a big difference in how women in different parts of Europe were discussing the experience of working from home with children.

“What I got from the UK is that women were really desperate with home-schooling and husbands not helping and all this kind of backlash to equality.” Though she has children herself it wasn’t a conversation she had heard so acutely in Finland

3. Put men to work – at home

In every country studied, survey data finds women have less free time than men because they are doing more unpaid work at home.

Erin Hye Won Kim at the University of Seoul found that fertility rates increased when men helped out more at home. She studied families with one child and found that when men did one more hour a week of domestic work at home it was related to a significant increase in the chances that that family would have a second child.

That reflects results from years of practice in Scandinavia. In Sweden fertility rates increased in the 2000s thanks, in part, to heavily subsidised childcare.

But mother and fathers are also offered generous leave after having a baby. Fathers now take about 30% of the number of days of parental leave that mothers do. “They are heavily involved, it’s not just a little marginal thing,” says Prof Gunnar Andersson. “They take the main responsibility for the child for a time in that first year and a half.”

And the patterns of childcare or housework that have been set in a child’s early life tend to continue as they get older. In Sweden, 73% of women do housework or cook for at least one hour every day and 56% of men, the European average is 74% of women and 34% of men.

“I think the signals you send are important”, says Prof Rotkirch. “The social signals and the political signals that we are there to support you, you will not be alone, you know, you will manage.”

For many years Nordic countries seemed to be sending the right signals – but not anymore.

Over the past decade fertility in Scandinavia has plummeted. In Sweden it’s been a steady decline but in Norway and Finland it has been drastic.

“Since we are among the happiest, family-friendliest countries on earth, it is very perplexing,” says Prof Rotkirch.

Does it really matter?

“From a demographic point of view, none of this actually needs to be a problem,” says Prof George Leeson of the Oxford Institute of Population Ageing.

Fertility rates in western Europe have been below replacement level since the 1970s but populations have continued to grow. “The population has just been refreshed and replenished by migration,” he says.

A shrinking workforce can be offset by allowing older people to stay in work – if they want to.

And falling populations can have positive effects in terms of climate change. “At the moment the fact that we’re not having as many children as our parents and grandparents did is giving the global village a bit of a breathing space,” says Prof Leeson.

There can also be surprising benefits to governments looking at fertility issues in a holistic way. When South Korea brought in working-hours legislation, reducing the working week from 44 to 40 hours, Erin Hye Won Kim found that men took more time to visit and support their elderly parents.

Ultimately policies should be about helping people to have the number of children they would like, says Prof Rotkirch.

“They influence child well-being and the well-being of people who have children. And that’s maybe the most important thing, that the children who are born have good lives.”