By P.K.Balachandran/Sunday Observer

Colombo, November 5: A perusal of the works of two outstanding Sri Lankan scholars on Emperor Ashoka, Prof.Patrick Olivelle and Dr. Ananda Guruge, reveals that as an individual, Ashoka was a committed Buddhist, but as a king, he was secular, using universally applicable moral principles to rule his vast Empire populated by people of different faiths and cultures.

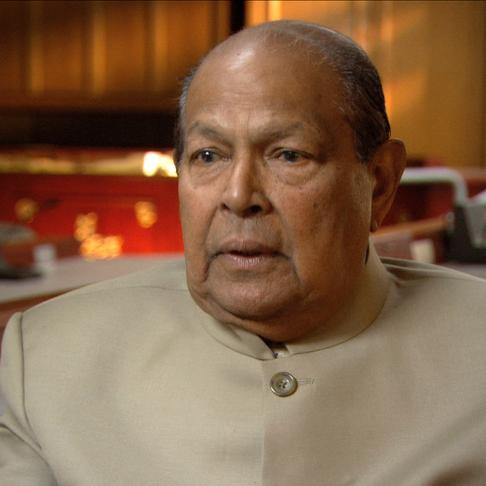

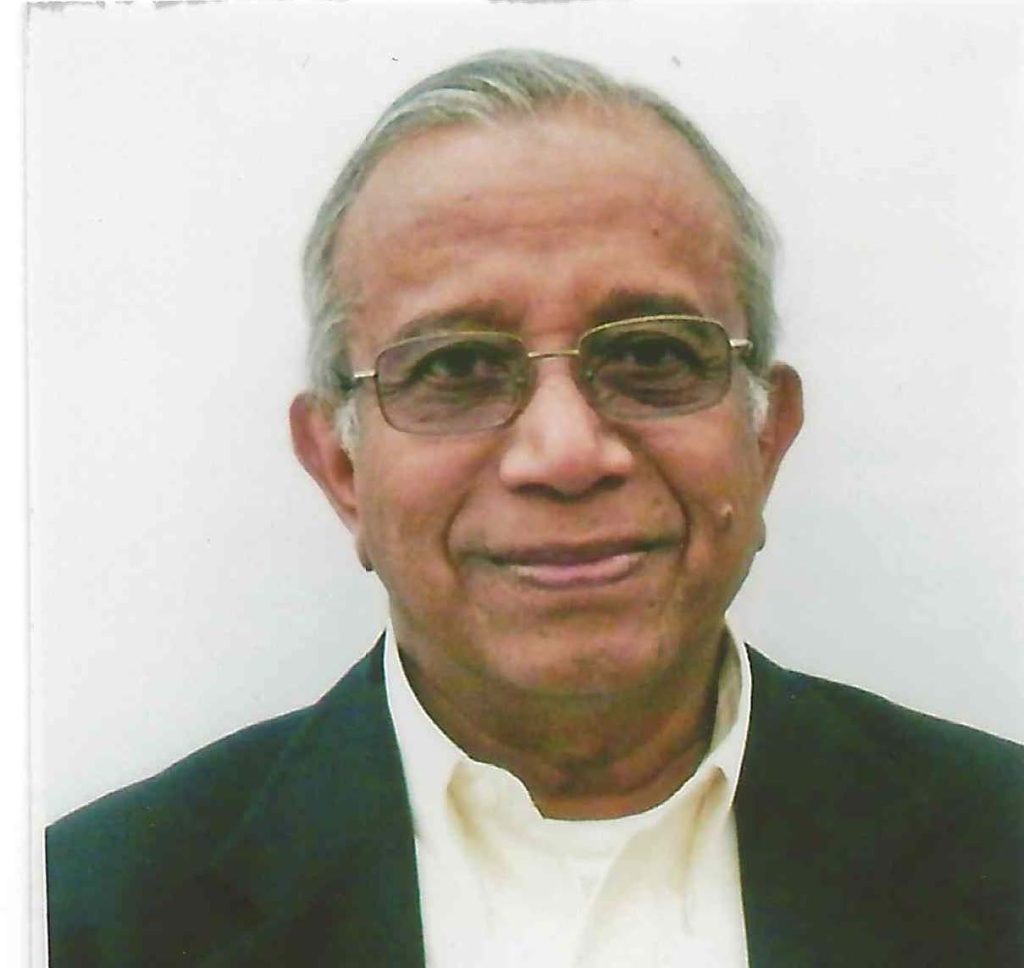

Patrick Olivelle is Emeritus Professor of Indology at the University of Texas at Austin USA and the late Dr. Ananda Guruge was Sri Lankan diplomat and Buddhist scholar.

Directly or indirectly, Ashoka ruled much of India from the far North up to the Chola and Kerala country in the deep south in the Third Century BC

Ashoka’s rock edicts, spread across the length and breadth of the Indian subcontinent, indicate his Raja Dharma or the principles of his rule. These were not Buddhist per se but more general, though in perfect harmony with Buddhism.

Ashoka chose to be eclectic or “ecumenical” as Patrick Olivelle would describe it (See: Ashoka: Portrait of a Philosopher King, HarperCollins 2023). This was because Ashoka’s realm had Buddhists, Hindus, Jains and followers of many other faiths as well.

Ashoka recognised various cultures and was attuned to cultural diversity, Olivelle says. He came from a multi-cultural family. Those days, kings married into kingly families from other cultures sometimes as part of a political settlement or a peace treaty. Some of these marriages were across religious and ethnic lines too. Ashoka’s father, Chandragupta Maurya, may have had Greek wives, because of his wars against the invading Greeks, Olivelle speculates.

There are two versions of Ashoka, according to Olivelle. One is the mythical version, which is popular in India, and the other is the realistic version. Olivelle presents the realistic version based entirely on Ashoka’s own writings, which are rock edicts found in various parts of his vast empire in the Indian subcontinent.

Olivelle told the Indian video channel The Wire that he had difficulty in piecing together Ashoka’s persona from his own writings because these were sparse. There were altogether only 4617 words in his edicts! Nevertheless, his submission is that the essence of Ashoka could be gleaned from the edicts.

Unsavoury Start

Ashoka had an unsavoury start as a ruler. He was initially known as “Chandashoka” or the Wicked Ashoka, who reportedly killed 99 of his brothers to capture the throne of Magadha, as he was not entitled to it because he was not the first-born of his father, king Bindusara.

It is not clear how he chose to become “Dharmashoka” but according to Ananda Guruge (Asoka: A Definitive Biography, Central Cultural Fund, 1993) in the first three years of his reign, he was in search of the “inner essence” of the then existing religions in India.

The search ended when he met a Buddhist monk, Samanera Nigrodha, in the fourth year of his reign and was impressed with his serenity. But there is no written material confirming this.

After becoming a Buddhist, Ashoka gave material gifts to monks and the Sangha. But otherwise, his conduct was not particularly Buddhist-like. However, in the seventh regnal year, Ashoka was recognised as the foremost patron of Buddhism in the sub-continent. He became an Upasaka after his son Mahinda and daughter Sanghamitta converted.

Critical Eleventh Regnal Year

But Guruge points out that in spite of adopting Buddhism, Ashoka committed “pogroms” against the Nirgranthas and Ajivakas for desecrating a Buddha statue. And in his ninth regnal year, he had no compunction about committing what Olivelle describes as “genocide” in the Kalinga war that was fought in what is now Odisha State in Eastern India. As per Ashoka’s own account, the war claimed 150,000 lives.

But the carnage traumatized Ashoka. He deeply regretted the carnage in his edicts. It proved to be a real turning point in his life both as a person and a ruler. After the Kalinga war he totally abjured war as an instrument of policy. He endeavoured to keep his realm together through moral force or moral principles. He promoted meetings and resolution of differences through discussions, rather than violence.

Though involved in administration, Ashoka nurtured Buddhism also. In his eleventh regnal year, he enunciated his own methods of propagating Buddhism and formulated a simple code of ethics that he propagated through his rock edicts, his officials and a variety of others including travellers and men of standing and scholarship like Brahmins.

People of all religious persuasions cooperated in this massive information and propaganda campaign because the principles had universal appeal, Guruge says.

It was also in the eleventh year of reign that he made his first pilgrimage to the Bodhi tree in Bodh Gaya. He built 84, 000 monasteries and initiated relic worship which is now central to Buddhism. Simultaneously, he kept cleaning up the monastic order through purges.

According to Olivelle, in all his major rock inscriptions, 14 of them, Ashoka never once mentioned Buddhism except in passing. “In the major inscriptions, Buddhism was in the background, not in the foreground,” Prof.Olivelle asserts.

This is reflected in the edicts in which Ashoka identifies himself as a king not a religious person or preacher, Olivelle says. “His edicts begin with this statement: Devānampiyo piyadasi lājā hevam āha — (The Beloved of Gods, KING Priyadarśi proclaims thus.).

Even in his letters to Buddhist monks Ashoka identifies himself as “raja/lāja” or King.

However, Olivelle points out that there are two inscriptions which are specifically Buddhist. In the Third century BC inscription from Bairat (Rajasthan), which is now in the Calcutta museum, Ashoka tells Buddhist monks what to read to brush up their knowledge of Buddhism. In another edict, he addresses monks who had caused dissension in the order and sought their expulsion from it.

Olivelle says that Ashoka’s edicts are about public matters but not about administration per se. Though in the edits Ashoka identifies himself as a king there is almost nothing about the details of governance in the edicts. There are no references to taxation or expenditure. The edicts are about public “ethics”.

Guruge, who gives a list of proscriptions, says that the edicts indicate Ashoka’s abhorrence of animal sacrifice. He advocates the reduction of meat consumption in royal households. He wants people to come together in meetings to resolve differences and exchange ideas and avoid persistent conflicts; cultivate medical plants, treat the sick, look after man and beast alike; respect parents and learned people including Brahmins. At the same time, Ashoka kept changing his prescriptions perhaps to suit changing needs.

Never Boastful

A notable point about Ashoka’s edicts is that he was never particularly keen on talking about his own conquests and achievements. According to Prof Olivelle, Ashoka “opens himself out in his writing to his people in a way that most kings or even politicians rarely do. In fact, he makes himself vulnerable.”

Ashoka has no compunction about publicly admitting that he committed a massacre in Kalinga that was tantamount to genocide and saying sorry about it. This is remarkable as genocide was common those days.

“Therefore, it is unique in world history that Ashoka admitted to genocide and apologised. No other ruler in the past or present has admitted to it,” Olivelle points out.

The other interesting aspect of Ashoka’s edicts is that the Emperor used only one language “Magadhi” but wrote in different scripts. He used the same language in Karnataka, Gujarat, Bengal, Nepal, thereby bringing in a certain uniformity. Olivelle says that this was not uncommon those days.

END