By Regina Mihindukulasuriya/The Print

Colombo, December 22: When you’re in Sri Lanka, it’s hard to understand how Christmas and New Year can be a festive affair. This was a crisis year, but the islanders seem happy. How come?

All I see on social media is happy, smiling people. Weddings at Colombo’s Waters Edge hotel, football fans flying off to Qatar for the FIFA World Cup, Christmas celebrations a week in advance at Hilton, post-carols drinks somewhere else fancy. At home, scheduled power cuts make for a candlelight dinner, with families enjoying pizza.

The Presidential Secretariat area, which was the nerve centre of the nearly four-month-long protests against the Gotabaya Rajapaksa government, is now lit up for Christmas — ‘VisitSriLanka’ says a sign. Decked-up reindeer are planted across the lawns that protesters had stormed into six months ago.

Was this the Sri Lanka I saw back in July? The very country struggling to get fuel standing in queues as long as the eye can see? I mean, annual inflation has dipped but it is still around 60 per cent. The loan from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) hasn’t come yet either, so what’s there to be happy about?

Maybe it’s the fact that there is now a quota to get your fuel, so the queues are gone. The average Sri Lankan is unsure where all the fuel is suddenly coming from. “India is giving us [fuel], right?” freelance writer Angie in Colombo asked me. “I don’t know how, but there are no more queues,” she says.

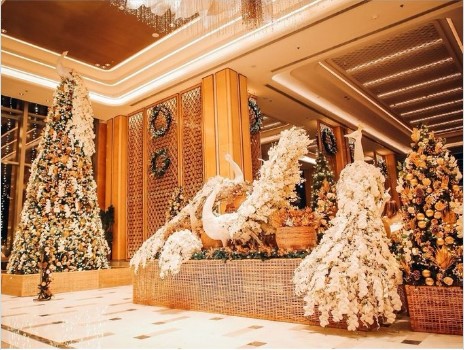

On Twitter, I posted a picture of Shangri-La Colombo’s dazzling Christmassy display and asked why there’s so much festivity in the country.

My god, it irked many.

“Would you have liked it if they hung empty plates instead of a decorated Christmas tree?” asked journalist Munza Mushtaq.

She has a point. And I kind of get it.

When non-Sri Lankans ask me ‘How is your family’, ‘Are they struggling’, ‘Do they have enough to eat’, they do so with compassion in their eyes. I feel like I disappoint them when I have no sob story to tell but only a blasé: “Yeah, things are okay.”

It’s hard to make them understand how it works. You just adapt to it and go with it. When I was in Sri Lanka in July, commuting was either walking for 30 minutes or paying four times for tuks (Sri Lankan three-wheelers). It’s tiring, but you learn to deal with it.

My friend Amanda, her husband, and his mother live in the same house and spend LKR 30,000 every three weeks on food and groceries. Savings are getting thinner. But average out these costs and it doesn’t sound too bad. A couple of months pass, and it’s not as shocking.

Maybe it’s a defence mechanism or just human nature, but it’s hard to feel shock, depression, and sadness for months at a stretch.

Let me give you a peek into a Sri Lankan’s psyche: Sometimes I catch a part of myself being happy for no reason, so the self-flagellating part reminds me that life is bleh, and mediocrity is nothing to be happy about. But then I tell myself that life will give me something to be devastated about soon enough, so I might as well be happy right now. This is perhaps the logic at work in the island country.

And the few privileged to be merry try to help the majority that aren’t. Angie took an LKR 500 cab ride she could ill afford to go to a friend’s mulled wine-making session. The cab driver had been telling her that he had no idea how he would buy new books and uniform for his daughter’s new school year.

One Twitter showed what the ground reality in the country looked like: “Some Sri Lankan and foreign journos are posting pictures of 5-star hotels and shopping malls. A young man came up to me and asked me to buy his sick father’s insulin.” Hospitals in Sri Lanka had stopped providing it since June 2021.

“These are the real victims of Sri Lanka’s economic crisis,” they added.

In an ongoing crisis, you never know what will happen next and what the worth of your money be. So enjoy while it lasts.

Besides, spending it is the best way to share your wealth, isn’t it?

(Edited by Humra Laeeq)

END