Rifat Halim/Tuppahis

Acres of newsprint have been devoted to Rishi Sunak’s rise. He is said to be the first Asian to occupy No. 10 Downing Street. This is not correct. Asia begins with the Tigris river. Boris Johnson’s great-grandfather was a Turkish politician. He should have been called Boris Kemal, as Johnson is the maiden name of his great-grandmother.

Sunak is definitely the first person of Indian Subcontinental origin, as well as the first Hindu, to hold this key position. However, not many are aware that Sunak’s path may have been forged by Ceylonese in 19th-century Britain.

Ceylon was separately administered from British India. It separated from British India in 1802 and was administered as a Crown Colony. But, the island was informally part of British India. Some Indian laws applied like the Indian Penal Code in Ceylon. The Ceylon Rupee was pegged to the Indian Rupee, which was in turn pegged to silver. Ceylonese who visited Britain were known as Indians or Hindus (irrespective of their religion). The word Hindu was then not a religious affiliation but a generic term for people from the subcontinent.

Three people from Ceylon were path-breakers for the vast Indian subcontinent. The first Asian to be called to the bar was a Sinhalese Christian, Harry Dias. The word “Cinghalese” was used to describe all from the island.

Sir Harry, as he was later known, was admitted to the English bar in 1847. Sir Harry’s admission to the Middle Temple was cheered throughout the British Empire. It was only in the mid-1830s that Catholics and Jews were allowed into the professions. In the case of Sir Harry, he was an Anglican, which dominated the British Establishment. He later became the first Sinhalese to be knighted.

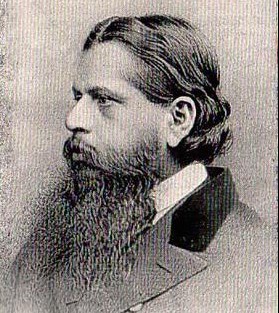

He paved the way for another statesman from Ceylon – Sir Muthu Coomaraswamy. Sir Muthu was from the most prominent family in Ceylon. He was a Tamil member of the Ceylon Legislative Council, a post that his family monopolized for many years. Sir Muthu became the first Hindu (in a religious sense) to be called to the Bar.

Sir Muthu was admitted to Lincoln’s Inn in 1862. Like Sunak, Sir Muthu may have taken his oaths with the Bhagavad Gita. He was the first non-Christian or non-Jew to be called to bar. Sir Muthu was a pathbreaker. The barrister was a bridge builder between the East and the West. He was an expert in Western and Eastern languages. While practicing law in London, he translated the Sanskrit play Harischandra into English. The play was performed for Queen Victoria in 1863 with Sir Muthu as a lead player.

He was not just a bridge builder in the arts. Sir Muthu was the first Asian to break into the upper echelons of British society. Prime Ministers David Gladstone and Lord Palmerston were his friends. Sir Muthu was one of the few from the East who socialized with the British establishment. In the 1860s, he once ran into a British official in a London bar. He had known the British official when he was a domineering administrator in Ceylon. The administrator had been condescending toward Sir Muthu. He had been treated as a lowly native. But in London, the tables were turned. The administrator was just minor colonial civil servant. Sir Muthu was moving in exalted circles. As it happened, Sir Muthu was about to attend a party hosted by Lord Palmerston that evening. Sir Muthu asked the official “will I meet you at Pam’s tonight?” to drive home the change in status.

Sir Muthu cleared the way for another Asian pioneer from Ceylon, Sir James Peiris. Sir James was a Sinhalese Christian who was an undergraduate at Cambridge in the 1880s. In 1882, Sir James was elected President of the Cambridge Union. Sir James was the first non-European President of the Oxford or Cambridge Union. No other colored was elected as President of the Oxford or Cambridge Union for nearly another fifty years.

Sir James was a Liberal in Britain and later became one of Ceylon’s leaders. He was Vice President of the Ceylon Legislative Council and was Acting Governor of Ceylon. He was one of the very few natives who acted as Governor in the British Empire.

There were other Asian path-breakers in the 19th century. In the 1890s, two Parsi gentlemen from Bombay Sir Dadabhai Naoroji and Sir Mancherjee Bhownaggree were elected to the House of Commons. Sunak’s elevation is the culmination of a long series of events.

The British have been broad-minded towards Asians since the 1800s. This is in contrast to many other societies. Sunak’s rise is not surprising. In fact, it was overdue given the advances made by Asians, particularly Ceylonese, in the 1800s.

END