Haar-i-Shalli, Kashmir, September 7 (AP):: Go to the southern villages in Kashmir and they’ll tell you stories about Burhan Wani, the Hizbul Mujahideen militant commander who was shot by the Indian security forces in July as he tried to escape through the back door of an isolated hideout.

Villagers say he’d play cricket with village boys, and visit orphanages. They say he’d pay for the weddings of poor young women.

In the weeks since Wani was killed on July 8, the stories have grown into mythology — a polite teenager who left home to become a Himalayan Robin Hood, a powerful insurgent commander who remained a man of peace — that it’s no longer clear what is true.

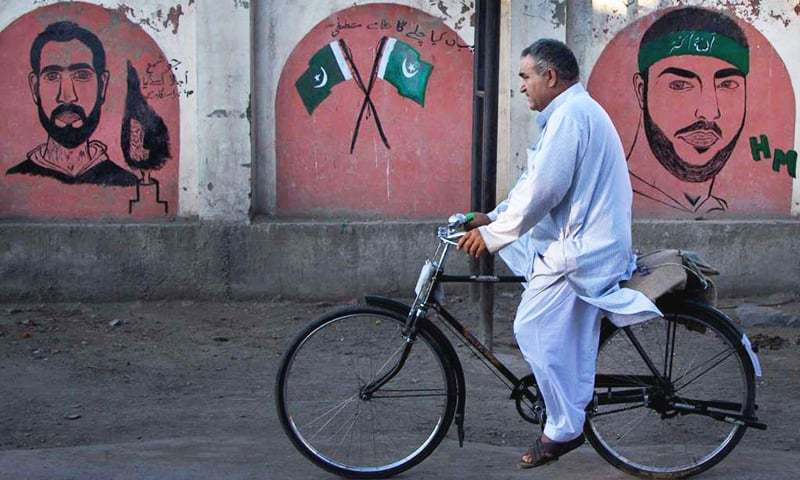

But in death, Wani has become something that India has long feared ─ a homegrown militant openly lionised across the embattled region, a powerful symbol against Indian rule who has united Kashmir’s many factions.

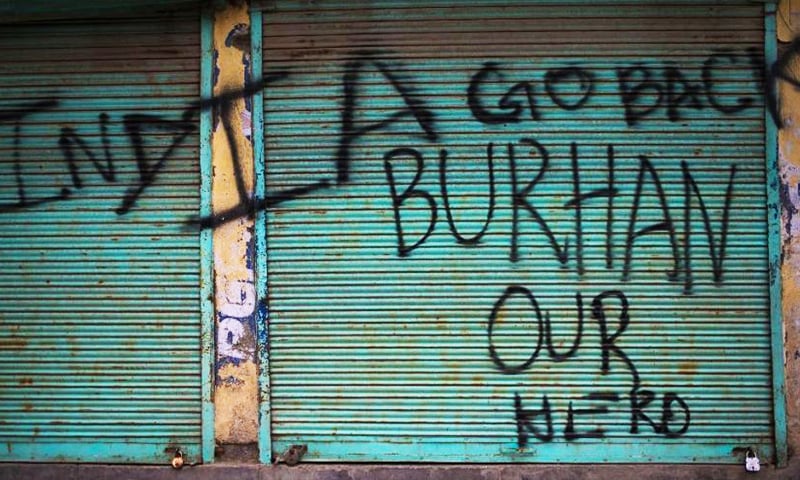

Today, rock-throwing high school students paint his name on shuttered storefronts — “Burhan our hero” — while everyone from fearsome insurgents to moderate politicians mourn him.

Wani had already rejuvenated the Hizbul Mujahideen, the largest of Kashmir’s IHK’s militant groups, attracting dozens of new recruits with postings on Facebook and other social media sites.

Young, handsome and charismatic, he looked more like a college student than a gunman. He sometimes posted photos of himself in the forests, a smile on his face and an assault rifle in his hands. If he was more a savvy recruiter than a menacing fighter, that only made him more popular.

But his killing, and the public fury it set off, now threaten to give new life to a militant movement in IHK that had withered in recent years, reduced to just a couple hundred fighters in scattered rebel outfits.

Wani’s death sent tens of thousands of protesters into Kashmir’s cities and villages, beginning a cycle of protest-and-crackdown that has left more than 70 civilians dead — most killed by Indian government forces — and thousands injured. Strikes, curfews and intermittent communications blackouts have effectively shuttered the region for more than seven weeks.

It has also helped make the militancy, which had once been at the extreme end of the Kashmiri independence movement, into something mainstream.

Villagers, who had learned long ago to hide any sympathy they felt for fighters, now speak of them openly with reverence and warmth.

Wani has become the face of the militants’ cause.

“He was a good man, a gentle man,” said Abdul Majeed, a farmer and elder in the village of Shaar-i-Shalli. “That’s why people cared about him.”

Late one night in mid-August, Indian soldiers forced their way into dozens of homes in Shaar-i-Shalli, driving dozens of men into the town square.

Over the next five hours, they beat the men so brutally that one villager died and a general was forced to apologize.

The soldiers, military officials later said, were offended that village elders had not wanted to meet them.

On a recent morning, Majeed and more than a dozen other men from the village crowded into the home of the dead man — Shabir Ahmed Mangoo had been a literature teacher at a nearby college, and his wife had just had their first baby — to talk about what had happened.

A scowling young man also named Shabir Ahmed (many men in the village share the same name) suddenly interrupted Majeed. He had jet black hair and a long beard, and could barely control his fury.

“People used to be afraid to say that they support the militants. But with the death of Burhan we have overcome that fear,” he said.

Militants have been fighting since the late 1980s for independence for IHK.

At its height, in the 1990s and early 2000s, a seemingly never-ending series of bloody insurgent attacks and brutal crackdowns by Indian security forces had given IHK the feel of an occupied state, a place of informers, torture centers and soldiers on nearly every corner.

The attacks of Sept 11, 2001, and subsequent United States pressure on Pakistan to rein in militants based there, were a major setback for the insurgent movement.

Indian security forces largely crushed the militancy after that, though popular demands for “azadi” — freedom — remained deeply ingrained in Kashmiri culture.

In the last decade the calls for freedom have shifted to unarmed uprisings, with tens of thousands of civilians repeatedly taking to the streets to protest Indian rule, often leading to street battles between rock-throwing residents and Indian troops.

Immense protests, some lasting for months, shook Kashmir in 2008 and 2010.

Today’s Kashmir is an often-contradictory place where bloody clashes mingle with skyrocketing real estate prices and increasing wealth (fed, in part, by Kashmiris working elsewhere in India or abroad).

It’s a place where you can buy high-end electronics or go shopping at Babelicious Fashions, but where you rarely go more than a few minutes without passing a heavily armed soldier or an armored military vehicle.

Increasingly, many Kashmiris see the recent uprisings as unsuccessful.

“In 2008 there were nonviolent protests, and no change. Then after the 2010 protests what happened? Nothing at all,” said a young protest leader who identified himself only as Mohammed, and who hinted at ties to Hizbul Mujahideen, saying he could find a Hizbul fighter “in a few minutes” if he wanted.

“This generation grew up with the idea of non-violence, no guns. But we got nothing” from that, he continued.

“What can we do but take up the gun?”

Most Muslim Kashmiris have been deeply distrustful of state politics since 2014, when a local political party vaulted itself to power by forming an alliance with the Hindu-nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), which has long advocated a hard-line response to any call for increased Kashmiri autonomy.

The latest protests, and the open support for insurgents, deeply worry India’s security establishment, which can no longer say the militant movement is a Pakistani creation.

The uprising has also gone on far longer than security officials expected. While most hope it will begin to fade after Eidul Azha, some worry it could last until the winter cold hits the region in November or December.

A high-ranking Indian security official, speaking on condition of anonymity in order to talk openly, worries that the brutality of India’s clampdowns, and its ineptness with such basic concerns as traffic enforcement and criminal investigations, have left Kashmiris with no trust at all in the government.

Instead, the public ends up glorifying men like Wani, and the stone-throwing teenagers.

They are young men with nicknames like “Bunker,” for his courage in attacking armored cars, which are often called bunkers, or “Discovery,” who acts as a scout for stone-throwers.

“This generation, it’s like gunpowder ready to explode,” the official said.

“When you make boys like this into heroes, then you have a big problem.”