By P.K.Balachandran/Sunday Observer

Colombo, August 18: Buddhism was the dominant religion in India from the 6th century BC to 7 th. Century AD. But it declined sharply thereafter and is today virtually defunct in the Indian sub-continent.

Scholars say that it is difficult to pinpoint the reason for this, firstly because of a paucity of material, and secondly because the causes of the decline varied widely depending upon the local context.

Be that as it may, it can be stated that Buddhism began to decline when an urban and trade-based society yielded place to a rural, agriculture-based feudal society. In India, unlike in Sri Lanka, Buddhism was based on the twin phenomena of urbanisation and trade, particularly long distance trade.

When urbanisation and trade declined in India, and were replaced by a rural-based agricultural economy with a locality-based feudal power structure, Buddhism declined and Hinduism (or Brahminism to be precise) rose.

A system based on spatial and social mobility which characterised the Buddhist era, was replaced by a static and immutably stratified and hierarchical social and value system, (the Hindu system as it were).

A casteless society envisioned by the Buddha was replaced by an immutable system of castes, striking at the very root of Buddhism.

Urban Religion

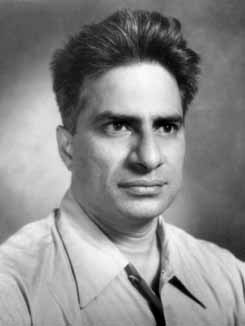

In his paper in the Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies (Vol Number 2, 1982, University of Wisconsin Madison), Balkrishna Govind Gokhale says that the use of iron tools, beginning from 7 th., Century BC, helped increase agricultural productivity. That in turn led to larger commodity surpluses, which became available for exchange through trade.

The easy availability of metals, copper and silver led to an increasing use of coinage, facilitating long-distance trade. These early coins were issued by guilds of bankers and merchants first, and later by political chieftains also, Gokhale says.

The emergence of well-defined trade routes bound together far-flung areas of the Indian subcontinent and also across the shores of India. These factors helped create a new and powerful class of merchants and bankers who became followers of the Buddha.

Urban Centres

According to Gokhale, four different types of urban centres emerged in Buddha’s time, Gokhale says. These were: (1) commercial towns like Savatthi; (2) political/administrative towns like Rajagaha; (3) tribal towns like Kapilavatthu; and (4) transportation centres like Ujjeni (Ujjain).

It was in urban areas like these that Buddhism evolved and thrived, he contends.

Savatthi (170 km North East of Lucknow in Uttar Pradesh) was on the banks of the Rapti (earlier called Achiravati) river. That river carried a considerable volume of commercial traffic. Savatthi was connected to both the sub-Himalayan highlands in the North as well as the riverine (Gangetic) territories to the south.

With a population of 57,000, Savatthi was the most important centre of trade as well as early Buddhism before the rise of imperial Magadha (Asoka’s dynasty) in what is now the Patna region in Bihar.

In his ministry of 45 years, the Buddha preached more in towns than in villages. He spent as many as 25 rain-retreats (vessas) in Savatthi according to both Gokhale and G.P.Malalasekera. The reason may have been the presence of powerful patrons such as Anathapindika and Visakha, as well as King Pasendi, Gokhale says.

Besides the cities and towns, a number of Nigamas also figure in accounts of the preaching of the Buddha. The term Nigama was used to indicate a predominantly mercantile town some populated predominantly by bankers called Setthis.

“We may assume that caravan leaders, merchants and bankers were as ubiquitous during the time of the Buddha, though not as numerous, as in the succeeding periods.”

”The Buddhism of our texts is a Buddhism predominantly of the cities, towns and market-places. Its social heroes are the great merchant-bankers and the new kings, perhaps in that order of importance. This kind of Buddhism drew its major social support from these classes and, in turn, reflected their social and spiritual concerns,” Gokhale says.

“The merchant classes needed a new spiritual-social orientation and value-system, which early Buddhism provided with its opposition to the old Vedic theology, sacrificial ritual, the dominance of the priest, and the emerging menacingly rigid social hierarchy,” he adds.

“These classes needed new socially-oriented ethical values, in which the individual (and his family) rather than the Varna-Jati ( or caste divisions) were the centrepiece. And the Buddha articulated such values.”

“The Buddha ignored caste distinctions in the matter of admission to and treatment of individuals within the Sangha. He ridiculed Brahmana pretensions to ritual purity and social eminence and insisted that a person should be judged by his individual virtue rather than his familial, class or social origins. This was precisely the demand of the new urban social classes who felt closer to the Buddha than to the traditional Brahmana and sacrifice-dominated Vedic cults,” Gokhale points out.

“These classes were not much interested in speculative metaphysics, for their emphasis was on practical and everyday concerns of making good in this world and assuring one’s welfare in the next. That is one of the reasons why so much of early Buddhism is addressed to ethical concerns rather than speculative metaphysics. The Buddha seems to have offered moral justification for social well-being and success,” he explains.

However, when the state began to be feudalised after the end of the Maurya empire (185 BC), the Sangha was also feudalised, as it depended on endowments of land.

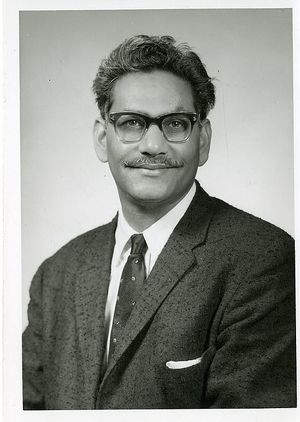

D.D.Kosambi

According to Marxist historian D.D.Kosambi, support for, or opposition of, rulers was key to the growth or decline of Buddhism in India. Buddhism grew during the rule of Emperor Asoka and the Mauryas but declined when the rulers turned against it.

King Shashanka of Bengal systematically destroyed Buddhist structures, cut down and burnt the sacred tree at Gaya under which the Buddha had attained enlightenment twelve centuries earlier. However, the Bo tree was soon nursed back to growth from a sprout discovered by Pumavarman, the last descendant of Ashoka.

King Harsha repulsed Shashanka, built many new Buddhist monasteries and fed a vast army of monks. The richly endowed University of Nalanda was at the zenith in his time.

But rot set in eventually. According to Kosambi, the Sangha had got addicted to luxurious living. Simplicity enjoined by the Buddha became conspicuous by its absence.

“The original function of the ever-wandering almsmen had been to explain the way of righteousness to all, in the simplest possible words, and the languages of the common people. The new class of disputatious residents of wealthy monasteries cared nothing for the villagers whose surplus product maintained them in luxury. The original rules laid down and followed by the Buddha had permitted only the mendicant’s trifling possessions without even the touch of gold, silver or ornaments. But the Buddhas of Ajanta are depicted wearing jewelled crowns, or seated upon the costliest thrones,” he pointed out.

Buddhism was hard to sustain. The administration of Buddhist structures gradually drifted into the hands of feudal elements. The self-contained village became the norm. Taxes had to be collected in kind and produce had to be consumed locally, for there was not enough trade to allow their conversion into cash.

Furthermore, transport of grain and raw material over long distances would have been most difficult under medieval Indian conditions.

And finally, Hindu society absorbed some key aspects of Buddhism. The Buddhist doctrine of ahimsa was admitted, if not practised. Vedic animal sacrifices were abandoned. The Buddha himself was absorbed in Hinduism by making him the ninth Avatar of Vishnu.

END