By P.K.Balachandran/Weekend Express

If someone were to say today, that the Pashtuns, also known as Pakhtuns or Pathans, living in Afghanistan and the Afghan-Pakistan border can swear by nonviolence, it will be dismissed as a figment of imagination.

The history of the culturally united but politically fragmented region and people does show that the Pashtuns have traditionally been restive, fiercely independent, rebellious and above all trigger-happy.

This is because they have been attacked by outsiders innumerable times in history. Their habitats have been constantly subjected to invasions right from the time of Alexander the Great to modern times. Czarist Russia, communist Soviet Union, the British Empire and American neo-imperialists have eyed their lands in succession.

The geographical location of the Pakhtun region is responsible for this unwelcome attraction. The Afghan-Pakistan region is en route to India and the warm waters of the Arabia Sea. Iranians had invaded India through this region several times in history, mainly to loot. Czarist Russians had wanted to gain access to the warm waters of the Arabian Sea and the Soviets wanted to expand their Asiatic Islamic Empire to include Islamic Afghanistan and make it communist. And the British and the Americans, who viewed Afghanistan as a buffer between them and the Czarist/Soviet Empires, intervened to check any intrusions from the North.

In the process, Afghanistan and the Afghan-Pakistan border regions were unsettled and ravaged with the people being forced to bear arms to resist outsiders tooth and nail.

Against this background, Mahatma Gandhi’s idea of gaining independence from the British by non-violent means would find no buyer her in that region. And yet it did.

At the turn of the 20 th.Century, a good number of Pakhtuns joined the non-violent Indian independence struggle. At that time, India had not been divided into India and Pakistan and the frontier region was part of India. The credit for turning the violent to the no-violent, goes to Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan, who came to be known as the “Frontier Gandhi.” He established an organization called the Khudai Khidmatgars or Servants of God. The KKs wore red shirts and paraded like a militant organization but were sworn to peaceful resistance to State oppression.

As to how Ghaffar Khan achieved this miracle is described by Rajmohan Gandhi in his book: “Ghaffar Khan: Non Violent Badshah of the Pakhtuns” (Penguin 2004).

Ghaffar Khan born in 1890, came from a pro-British family of notables from Utmanzai now in the Afghan-Pakistan border region. His father, Behram Khan, had broken the Pakhtun tradition of not sending their children to Christian missionary schools and sent Ghaffar to a school run by one Rev.Wigram. This kindled in Ghaffar an interest in spreading modern as opposed a purely Quranic education to the Pakhtuns and opening them to new ideas. A substantial part of the Khudai Kidmadgars’ activities was in the field of education. He started a modern school in 1910 and independent madrasahs also. Subsequently he opened more modern schools.

Behram Khan influenced young Ghaffar in another important way. He had given up a hallowed Pakhtun tradition, namely, feuding called “Badla” in Pushto. Behram had declared that he was opting out of it and forgave all those who had feuded with his family for generations. This inspired Ghaffar Khan to make peace making among warring tribes. That was one of KK’s major missions.

But like his father, Ghaffar would never bow to oppression. He would resist it peacefully, a technique and temperament he imbibed when he came under the spell of Mahatma Gandhi in the 19202.

But before that he became anti-British. He felt that the British were ungrateful to the Pakhtuns who had helped the British crush the mutiny in the Indian army in 1857 and also capture Baghdad and Jeruselem. Distrusting the Pakhtuns (out of the fear of Russia), the British enacted the draconian Frontier Crimes Regulation to exercise tight control over them. The British officers’ arrogance towards Pakhtun recruits in the Foreign Guides Regiment (which Ghaffar hade joined) also made him anti-British.

It is not known as to how Ghaffar became political person and a freedom fighter to boot. But he was a thoughtful and brooding young man always. He would go to Islamic leaders and others in search of a path to redeem his people. It was during this quest that e chanced upon Gandhi.

Ghaffar Khan’s opposition to the Frontier Crimes Regulation matched Gandhi’s opposition to the equally draconian Rowlatt Act. Gandhi had unleashed non-violent resistance against the Rowlatt Act. This technique appealed to the peaceable but tough Ghaffar. He joined the anti-Rowlatt Act agitation and was jailed. He was designated as a “dangerous convict” and his feet were chained.

Strangely, the highly suspicious British rulers felt that the schools being set up by Ghaffar for the Pakhtuns had a seditious agenda. Chief Commissioner Sir John Maffey told Behram Khan to ask his son to quit his educational activities and stay at home. Otherwise the son would have to face the consequences. When the British questioned him personally, Ghaffar said that the schools he was running were to be like the missionary school he went to. Nevertheless, he was arrested and was imprisoned in stinking hell hole in 1921.

But Ghaffar’s spirit was indomitable. He followed Gandhi’s path and toured the frontier with the latter in 1939 for over a month. Convinced that Ghaffar was a true adherent of the creed of non-violent resistance, Gandhi said of him in 1939: “As early as 1920, Badshah (Ghaffar) Khan had come to recognize in non-violence a weapon, the mightiest in the world, and his choice was made.”

And Ghaffar stood by the creed right through his political life, even though he continued to fight for the inclusion of the frontier region in India rather than Pakistan in 1947, later for the inclusion of it in Pakhtun-dominated Afghanistan and still later, for autonomy within Pakistan. For every ruler Ghaffar was a thorn in the flesh whether they were the British or Pakstanis.

During a visit to New Delhi in 1981, Ghaffar Khan said that he believed that the conditions of the Pakhtuns would never improve if they did not give up the habit drawing blood for blood. “Violence creates hatred and fear. Nonviolence generates love and makes one bold,” he said.

It is not certain if Ghaffar Khan’s philosophy would have worked in the years that followed his era as the leader of the Pakhtuns. The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, the fostering of the Taliban by the US and Pakistan to be a counter to Soviet hegemony, the establishment of Shariah rule under the Taliban and the subsequent forcible ouster of the Taliban by the US, might have made peaceful resistance an impossibility.

Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan, who died in 1988, had lived to see at least a part of these developments. But still he might have advocated no-violent resistance. He could very well justify the stand by pointing out that violence has indeed taken a very heavy toll.

While Afghanistan is in a shambles, the frontier region of Pakistan is still a battle ground, with Islamic militants fighting the Pakistani army. For the Pakhtuns, peace and prosperity are still a far cry.

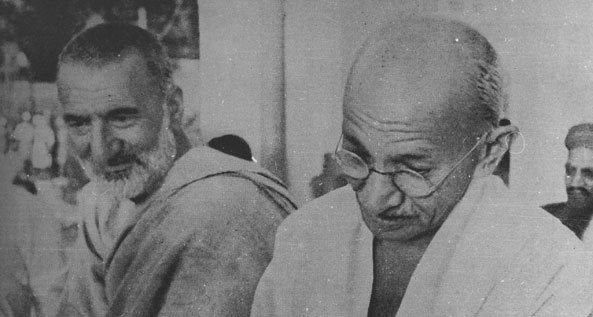

(The image at the top shows Ghaffar Khan with Gandhi)