By P.K.Balachandran/Daily News

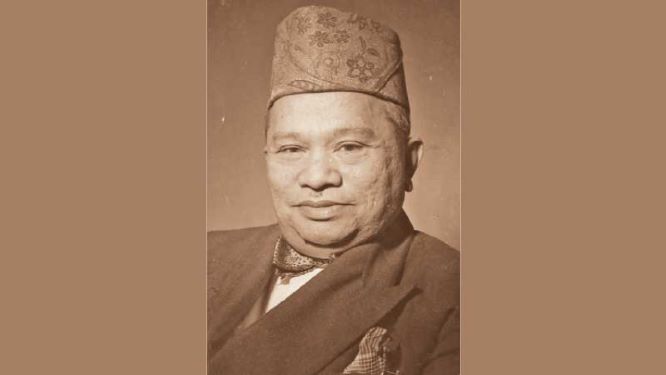

Colombo, January 1: Dr. Tuan Burhanudeen Jayah laid the foundation for the Muslim rights movement in Sri Lanka, and shaped the movement in such a way that communal or sectional interest was never allowed to override the collective national interest. No wonder then, T.B. Jayah, as he was known, is regarded as a national figure rather than as a communal leader.

Born on January 1, 1890 in Galagedara in the family of a religious-mind Malay policeman, it is not surprising that Jayah was given a good grounding in the Holy Quran at an early age. Thereon, Islamic ideals became the bedrock of his life both as a zealous missionary promoting modern education among the usually traditional Lankan Muslims and as a politician awakening the largely apolitical community to the need for political action to ensure their rightful place in Lanka’s multi-ethnic society.

Despite his modest and somewhat conservative background, T.B. Jayah was sent to S. Thomas’ College where he studied the European Classics and went on to become a Classics teacher at Ananda College, the bastion of Sinhala-Buddhist nationalism. It is with this well-rounded and cosmopolitan background that Jayah went about campaigning for a modern liberal education among Lankan Muslims who were mostly in trade and fearful of the impact of modern liberal education on their wards.

But Jayah reminded the community how, in earlier times, Islam promoted fresh thought and its followers led the world in science. Influenced by the great modern Indian Muslim leaders Sir Sayed Ahmad Khan and Badrudeen Tyabji, Jayah co-founded Zahira College, and was its Principal for years, seeing it through several crises. A centre of liberal education within the rubric of Islamic values, Zahira under Jayah, had played host to inspiring Indian nationalist leaders like Mahatma Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru and Sarojini Naidu. To make modern education available to Muslims outside Colombo, Jayah opened branches at various places in the island.

Jayah played a national role in politics while being a ‘Muslim’ leader. He awakened the Muslims to the need to shed their differences and come together to fight for their rights in a democratic and competitive Sri Lanka where unorganized communities could be dominated and eventually erased.

The story of Jayah’s entry into politics, his advocacy of Muslim rights and his unifying role are told engagingly by Enver C. Ahlip in his book: A life serene: A life sketch of Al Haj. Dr. T.B. Jayah published by the National Institute of Education Press with a forward by former Prime Minister Dudley Senanayake. Premier Senanayake said that Jayah had played “an important part in bringing the communities of this country together for the achievement of independence.”

When Jayah wanted to contest one of the three seats set apart for Muslims in the Legislative Council, the politically insular Malay community, to which he belonged, discouraged him saying that he was “foolhardy.” But the Moors, who were the majority among the Muslims of Sri Lanka and were also the most progressive, were enthusiastic. To enable him to have a Muslim platform, Kamar Cassim, the President of the Ceylon Muslim Association, vacated his post and gave it to Jayah.

Jayah began his political career by trying to get Muslim Government employees permission to go for the Friday noon prayers. These prayers have to be said not alone but in a congregation and that is enjoined on all Muslims. Though the demand was simple and innocuous, it took a long time to be conceded. The All Ceylon Malay Association had made the request in 1923 but it had fallen on deaf ears, forcing Jayah to take it up in 1925 and keep reminding the authorities about it.

This episode made Jayah realize that if the Muslims lost opportunities to set matters of discrimination right “an overzealous bureaucracy can wreck the well-being of a minority, which, because of its ineffective numerical strength, can be all too easily discriminated against.”

Enver Ahlip writes that Jayah made a strong plea that minorities be consulted before any legislation which might affect their susceptibilities was taken up. “The scope of such discrimination may be unclear to the majority community,” he felt and tried to educate them in a reasonable way, whenever the need arose.

On July 31, 1925, he told the Legislative Council: “The Government should not come to hasty conclusions in framing legislation, particularly when it is likely to affect certain communities, at least the religious views of some communities.” He went on to plead that if the abuses in certain communities had to be corrected, the wishes of the communities concerned should be ascertained beforehand.

Jayah further said: “It may be that the Government is actuated by the best motives and the best of intentions, but that is no reason why the wishes of the people should not be consulted before hand.”

When the Muslim Marriage and Divorce Act came up for discussion in the State Council in August 27, 1941, Jayah asked if any action was taken on the report of the committee which went into the Muslim Marriage Ordinance and made some recommendations with the help of the eminent jurist, Justice Akbar. He was told that the matter would be looked into. But when asked the same question in 1945, the answer was still the same: “We are looking into it.”

When the Donoughmore Commission on the future constitution of Sri Lanka came to the island in 1927, the All Ceylon Muslim League (ACML) which Jayah headed, submitted memoranda to the commission in Colombo, Kandy and Galle. While backing the demand for adult franchise for all Sri Lankans, the ACML also asked for adequate representation for the Muslims.

According to Ahlip, the Muslim case was spoilt when the Muslim community leaders failed to heed Jayah’s advice to sink their differences and present a united front before the commission. While the Moors said that they were indigenous to Sri Lanka and therefore entitled to special consideration, the Malays said they were distinct and therefore needed separate representation. And everybody tried to isolate Indian Muslims, who were themselves a disunited group differing in language and place of origin in India.

The result was devastating, as Ahlip put it: “The commissioners were so puzzled that they decided to abolish communal representation altogether, calling it a canker in the body politic.”

This came as a rude shock to Jayah and his ACML. They strongly felt that the Muslims needed reserved seats because they were scattered in the island that they would never be able to elect even one to the council. The ACML representatives collected 50,000 signatures and sailed to England to meet the Secretary of State for the Colonies. The team was led by Jayah and had as other members M. Mahroof, C. Abdul Cader of Batticaloa and Shulam, a leading merchant. However, the Secretary of State said that he could do nothing about it because the State Council had passed the Donoughmore Constitution (albeit only by a two-vote majority).

Jayah blamed the majority community for the attitude of the Colonial authorities. The majority community had portrayed the minorities’ demand for communal representation as a demand for exclusive privileges. The minorities were unwilling to integrate with the majority, they said.

“When a whole community is put to action by an instinct for self-preservation, be it rightly or wrongly, is it proper for the members of the majority community, if they do really love the country and realize that the minorities too are entitled to a place in the sun, to misinterpret our cause and put impediments on our way?” Jayah asked.

But Jayah’s plea fell on deaf ears. According to Ahlip: “The Sinhala leaders of the day had made up their minds that minority demands would undermine their concept of a National Government. To them, the majority view must prevail and any concession to minority demands would, to that extent, negate the concept of a National Government.”

“The majority community felt that any projection of minority interests was ipso facto contrary to the national interest,” Ahlip said and added: “This was the beginning of the hardening of the attitude of the Sinhala elite to minority aspirations already evident in the activities of the Ceylon National Congress in the ungracious manner in which it disposed of Sir Ponnambalam Ramanathan.”

Jayah argued that the Muslims were an integral part of the Ceylonese nation and that the country could not progress without the contribution of all sections of the country. But that was to no effect. Jayah made his pleas on behalf of the Muslims again before the Soulbury Commission, which also turned down the demand for communal representation.

However, despite these bitter experiences, Jayah was a staunch supporter of Sri Lanka’s independence. He campaigned for the creation of the Muslim state of Pakistan but would not countenance the division of Sri Lanka. He told the State Council that freedom for Sri Lanka was more important than “mere communal advantage.” Jayah passed away on June 1, 1960, aged 70.

END