By P.K.Balachandran/Sunday Observer

Colombo, September 15: Sri Lanka and Bengal have links going back to Prince Vijaya who came to Sri Lanka from Bengal with his retinue in 543 BC and established the island’s first dynasty that ruled for 609 years.

But Buddhism became an important strand in the relationship, only when it was introduced to Sri Lanka by Prince Mahinda, son of Emperor Asoka of Magadha in Bihar next to Bengal. Mahinda and his sister Sanghamitra were sent to Sri Lanka by Asoka at the request of the Lankan King Devanampiya Tissa (250 BC – 210 BC).

From ancient times to the early medieval period, Sri Lanka and Bengal were part of a large All-Asian Buddhist fraternity. But the later Medieval period saw the eclipse of Buddhism in India, partly due to the rise of Brahminical Hinduism and partly due to Islamic iconoclasm. Sri Lanka however remained Buddhist, with little or no contact with Bengal.

After a very long gap, close links between Sri Lanka and Bengal were again forged during British rule in both countries in the late and 19th. and 20 th. centuries.

The catalyst for this was the establishment of the Mahabodhi Society in Calcutta and the movement to secure Bodh Gaya from a Hindu Mahant. The movement brought Buddhist activists and scholars from Bengal and Sri Lanka together. Some of the key participants in that movement led by Sri Lankan Anagarika Dharmapala, were Bengali intellectuals.

Since Calcutta was the capital of British India till 1911, Sri Lankan Buddhists’ links with India were essentially with Calcutta and Bengal, many of whose scholars were engaged in research on Buddhism.

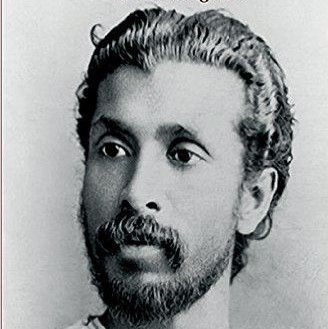

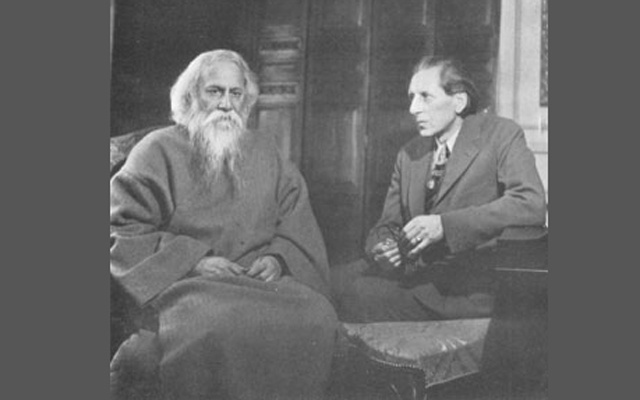

At that time, Bengal had an impact on Sri Lankan art, music and drama also. The Lankan art historian Ananda Coomaraswamy had a close relationship with Rabindranath Tagore. Composer Ananda Samarakoon was influenced by Rabindra Sangeet. Singer Sunil Shantha learnt music at Tagore’s Shantiniketan. Dancer Chitrasena was also a product of Shantiniketan. Modern-day Film maker Vimukthi Jayasundara even directed a Bengali-language commercial film Chatrak.

Rabindranath Tagore visited Sri Lanka thrice, 1922, 1928 and 1934 to rousing receptions in Colombo, Galle, Kandy and Jaffna. Described as a “Maha Kavi” in the island, his speeches in leading schools like Ananda, Mahinda, Trinity and Jaffna Central, were well covered in the media. When he staged his dance drama Shap Mochan to packed halls over six days, SWRD Bandaranaike, future Prime Minister reviewed it the Ceylon Daily News saying it was “a revelation of art at its highest

Today, the Indian State of West Bengal is overwhelmingly Hindu and East Bengal (now Bangladesh) is overwhelmingly Muslim. But Buddhism was popular in both Bengals till the 13 th.Century though its fortunes varied from time to time with regime changes, says Rup Kumar Barman in the Journal of Education and Buddhist Studies,Vol. 2, No. 2, December 2022.

According to Barman, Bengal had maintained a very close relationship with Buddhism since its introduction by Gautama Buddha (623 BC-543 BC) in neighbouring Magadha. Myanmarese sources suggest that the Buddha visited Sudharmapur in ancient Myanmar in 580 BC and that he would have travelled through Bengal. This explains why Buddhism became the chief religion in the Chittagong Hill Tracts in Bangladesh bordering Myanmar.

From the time of the Haryanka dynasty ( 546 BC to 413 BC) to the Mauryan dynasty (320 BC to 200 BC), Buddhism was popular in various parts of Bengal. There is archaeological evidence of this in Pundravardhan (North Bengal).

Buddhism gained strength in the reign of the Mauryan King of Ashoka (273-232 BC) after he converted to Buddhism following the carnage he saw in the Battle of Kalinga (261 BC).

The ‘Third Buddhist Council’ was held at his initiative in the Third Century BC. The most significant outcome of the Third Buddhist Council was that the Tripitakas got a written form and a decision was taken to send Buddhist missions to different countries including Sri Lanka.

But Buddhism suffered a setback in India under the Sunga rulers (187 BC to 75 BC) especially its founder, Pushyamithra Sunga. But there was a tremendous boost under the Kushana rulers (1st Century BC), especially Kanishka (78 AD -103 AD). The Fourth Buddhist Council was held and in that two different ways of attaining Nirvana, the Hinajana and Mahajana, order were recognised. Later, the Hinajanis identified themselves as Theravadis, according to Barman.

Buddhism flourished in Bengal at that time, as noted by the Chinese travellers Hieun Tsang and I-Tsing. They recorded the existence of Stupas and Sangharams and Buddhists in Samatata (East Bengal), Karnasubarna (Central Bengal), Tamralipta (South-western Bengal) and Pundravardhana (North Bengal).

The early Gupta rulers (4th – 6th Century AD), especially King Sasanka of Gauda (606-636 AD), opposed Buddhism and attempted to destroy monasteries. But still, Bengal produced a prominent Buddhist scholar in the 6th Century CE named Silabhadra (529 AD-645 AD).

Buddhism got royal patronage again with the rise of the Pala Empire 750 AD-1161 AD). Shri Gopala, the founder of the Pala dynasty, had established several Buddhist monasteries in Nalanda (in present–day Bihar) and other places of his kingdom. His son Dharmapala, the greatest Pala king (770 AD-810 AD), founded the famous Bikramsila University. Both Nalanda and Bikramsila were patronized by Buddhist scholars from various Asian countries.

State patronage for Buddhism was extended by King Devapala (810 AD-845 AD) which ceased after his death. The Palas could not maintain their economic status, plus internal conflicts and invasions also contributed to their decline. By the 12 th Century AD they had vanished

During the rule of the Palas, Buddhism experienced changes including the introduction of Tantricism. Different schools of Trantricism like (i) Mantrajan, (ii) Bajrajan, (iii) Kalachakrajan, and (iv) Sahajajan got acceptance in Bengal through the writings and propaganda of the Buddhist ‘Siddhyacharyas’.

The Buddhist Siddhacharyas eventually contributed to the growth of different Buddhist sects in Bengal (like the Nathadharma, Kaulyadharma, Abadhuta, Sahajia, and Baul). These trends encouraged the lower castes of Bengal to embrace Buddhism.

Buddhism began to decline with the rise of the Sena dynasty (1095 AD to 1207 AD). It was a serious challenge to the existence of Buddhism in Bengal as the Senas aggressively revived Brahmanical Hinduism and denied patronage to Buddhist deities, institutions, and scholars.

At the same time, the invasion of Bakhtiyar Khilji (1207 CE) took place. Many Brahmanical Hindus and Buddhists of Bengal were either killed or were forced to flee. Bakhtiyar Khalji himself is said to have destroyed Nalanda, Bikramsila, and many other Buddhist institutions that were full of Buddhist texts. Many Buddhist monks and scholars fled from the country and took shelter in Nepal, Tibet, Odisha, and Myanmar. Buddhist monasteries were deserted. Many of them were transformed into mosques.

Under the rule of the Bengal Sultans (Muslim rulers) from 1200 AD to 1538 AD), the Mughals (1576 AD-1707 AD), and the Bengal Nawabs (1707 AD-1772 AD), Buddhists and Buddhism did not get any support from the State.

During the colonial period (1757 to 1947 AD), Buddhism saw a revival particularly in early 20 th., Century. But the Partition of Bengal in 1947 into a Hindu India and a Muslim Pakistan, deeply harmed Buddhism. Buddhists migrated from Muslim Bengal (then East Pakistan) to Hindu Bengal (West Bengal in India) as refugees.

Nevertheless, they built monasteries, Sanghasrams (spiritual hermitage), temples, and institutions in Kolkata, sub-Himalayan Bengal, and certain other districts of West Bengal. They have preserved and maintained the Buddhist socio-cultural traditions that they had inherited from South-Eastern Bengal, now part of Bangladesh.

Buddhism has survived in certain regions of Bengal, especially in the South Eastern part of present-day Bangladesh. The Chakmas, Arakanese, Marmas, Rakhains, and Mag Baruars maintain Buddhist traditions in their own way.

On the other hand, Tibetan Buddhism influenced the Himalayan kingdoms of north Bengal (Sikkim and Bhutan).

It has also been noticed that the Bengali-speaking Dalits of West Bengal, after their conversion to Neo-Buddhism in the 1950s, had set up their own Buddhist organizations such as the Poundra Kshatriya Unnayan Parishad (in 1970), Champahati Ambedkar Samity (in 1988), Sudarban Ambedkar Samity (in 2001), Bharatiya Poundra Society (in 2006), and Poundra Mahasangha (in 2008). These are quite active in the Sundarban Delta (Coastal West Bengal).

At the same time, Mulnibashi Samity (2006) and Gautam Buddha Guidance Academy (2011) are engaged among the Poundras, Namasudras, Rajbanshis, Jalia Kaibartya, and other Dalit communities of West Bengal, Barman reports. These organizations are popularizing Buddhist culture and thought among the Dalits of West Bengal.

END