Through the gurukuls, set up in Mumbai and Bhubaneshwar, Pt. Hariprasad Chaurasia wants to make training in classical music accessible to young enthusiasts

By Chitra Swaminathan/The Hindu

The sky is overcast with dark clouds. The intermittent heavy showers haven’t dampened Mumbai’s celebratory spirit. Rows of stalls along the roads selling idols teem with people even as dhol tasha pathaks (percussion troupes) play vigorously during their annual Ganesh Utsav outing. But away from all the festive frenzy, the soothing notes of the bansuri permeate Vrindaban Gurukul in Versova. Evening walkers stop by the two-decade-old large orange building to bow before its beautiful prayer room with a glass facade.

As you open the gate, you see Pt. Hariprasad Chaurasia sitting near the entrance, sipping tea, with the bansuri placed on his lap. He greets you with a warm smile. A striking oil portrait of him, made by one of his admirers from Turkey, hangs behind. The walls of the adjacent spacious classroom have more paintings depicting the maestro’s many moods. There is also a bust of Ustad Allauddin Khan, the legend of the Maihar gharana and father of the inimitable Annapurna Devi, whose black-and-white photograph adorns the practice space.

Pt. Hariprasad Chaurasia at his gurukul ‘Vrindaban’ in Mumbai. | Photo Credit: EMMANUAL YOGINI

Looking at the picture, Pt. Chaurasia, who turned 85 this July, recalls how under guruma’s (Annapurna Devi) guidance he made the bansuri, associated with the pastoral tradition, reproduce every classical nuance. He seamlessly incorporated the alaap, jod and jhala of the Senia-Dhrupad ang. It gave a new tonal quality to the instrument.

Pt. Chaurasia slowly walks up to occupy the silk-wrapped seat on a raised platform. Years have not diminished his uncanny ability to watch over the activities in the gurukul. He seems to be the master of all he surveys.

For Pt. Hariprasad Chaurasia playing the flute is like having a conversation with Krishna. The maestro in the prayer room of his Vrindaban Gurukul in Mumbai. | Photo Credit: EMMANUAL YOGINI

Vrindaban is a conventional gurukul where young learners live and train in music for free. Reorienting itself to face contemporary challenges, the gurukul (a second one was established in Bhubaneshwar in 2010) has also been offering online courses and organises workshops and interactive programmes.

Vrindaban Gurukul in Mumbai. | Photo Credit: Chitra Swaminathan

“I am delighted to see more girls coming to learn. Since I learnt it the hard way, spending almost three years convincing guruma to teach me, I wanted to start gurukuls to make training accessible to young enthusiasts,” says Pt. Chaurasia even as you see three girls busy with their riyaz. Pico, the resident pet dog, sits in front of them quietly listening to the meends and gamaks.

Pt. Chaurasia, who used to travel for most part of the year, performing nearly 200 concerts, and teaching at international conservatories, now divides his time between the two gurukuls. “Bahut ghoom aur bajaa liya, ab baitke sununga bachon ko (enough of travelling and concerts, I now want to listen to these youngsters),” says the veteran, speaking softly, giving hints of fatigue due to old age. But throughout the 45-minute conversation, he never fails to make a point on things, including politics, he feels strongly about.

“Whether artistes, politicians or institutions, I see a fear of commitment in all,” he says. “You set out to do something but don’t want to finish or achieve it. I tell my students to first tune their mind and then the instrument. If I had not done so, I would have remained in the akhada (wrestling ring),” he adds.

Pt. Chaurasia watching his students perform at Vrindaban Gurukul in Mumbai. | Photo Credit: VIJAY BATE

Though among the few Indian classical musicians who have always had sell-out concerts both in the country and abroad, Pt. Chaurasia does not belong to any hoary gharana or a lineage that can be traced down several generations. “My father was a professional wrestler and wanted me to follow suit. I did so for a brief while to make him happy. I wondered of what use was this show of physical strength. I felt music was a better way to gain recognition. Every morning, on the pretext of going to the temple, I would go to a friend’s house to practise. The radio was my first guru,” he says with a laugh.

Two totally unconnected worlds, yet Pt. Chaurasia made the transition from one to the other, and how!

“I owe it to the akhada for preparing me to fight life’s battles. It taught me to handle both the rise and the fall.”

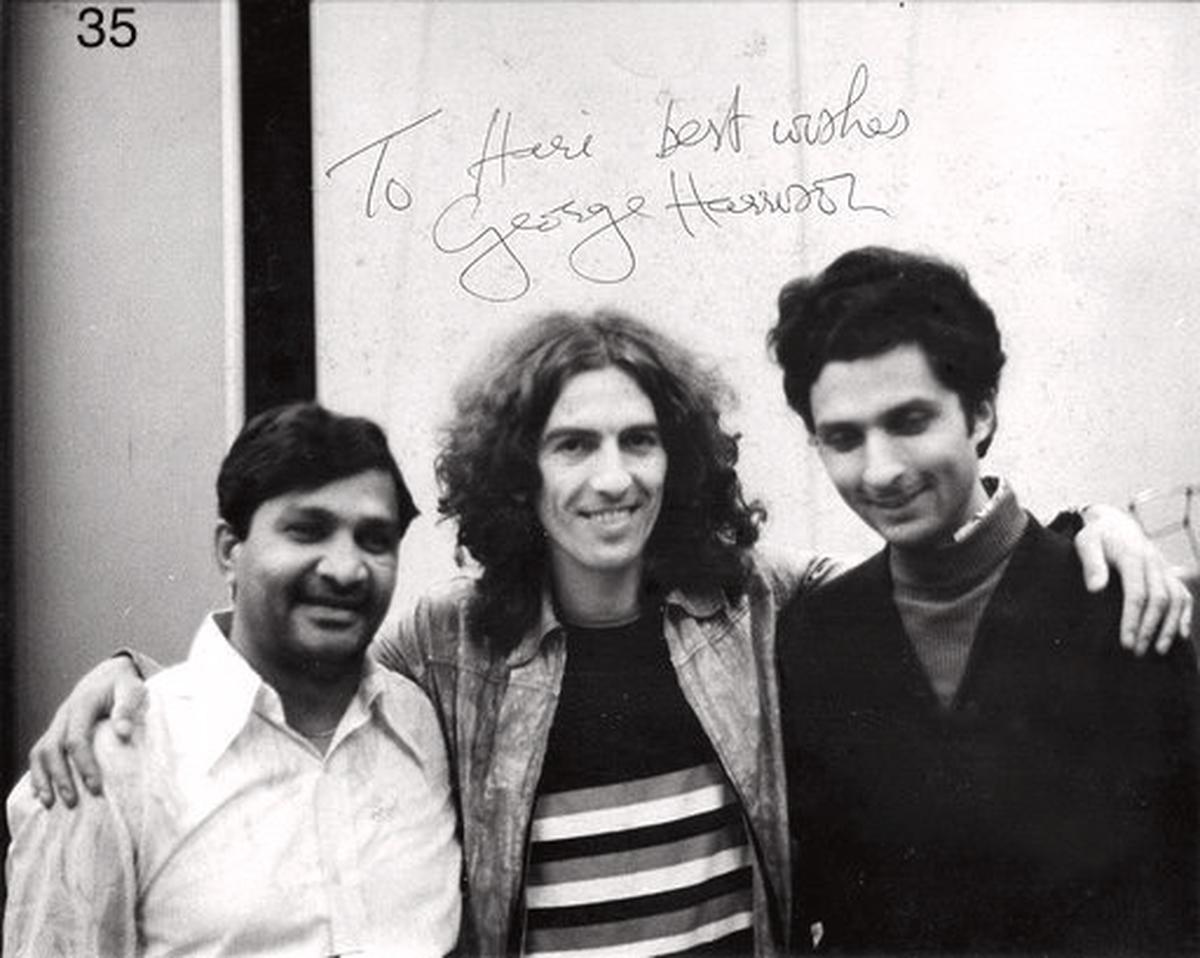

Hariprasad Chaurasia and Shivkumar Sharma with George Harrison of the Beatles | Photo Credit: Special Arrangement

Pt. Chaurasia worked as a stenographer to support the family before moving to Cuttack to join All India Radio. After a few years, he was transferred to Bombay, the city that turned his dreams into reality. “It is here that I met my dear friend and creative partner, Pt. Shivkumar Sharma. I also began composing for films. It gave me the opportunity to experiment with music. Though my heart belongs to classical music, I have always enjoyed working across styles and genres. That’s how I collaborated with John McLaughlin, Jan Garbarek and Ian Anderson.”

For Pt. Chaurasia playing the flute is like having a conversation with Krishna. “It is a very physical and immersive experience because you must create the sound first within your body. I often feel the air comes straight from my heart, carrying with it my vulnerabilities and strengths.”

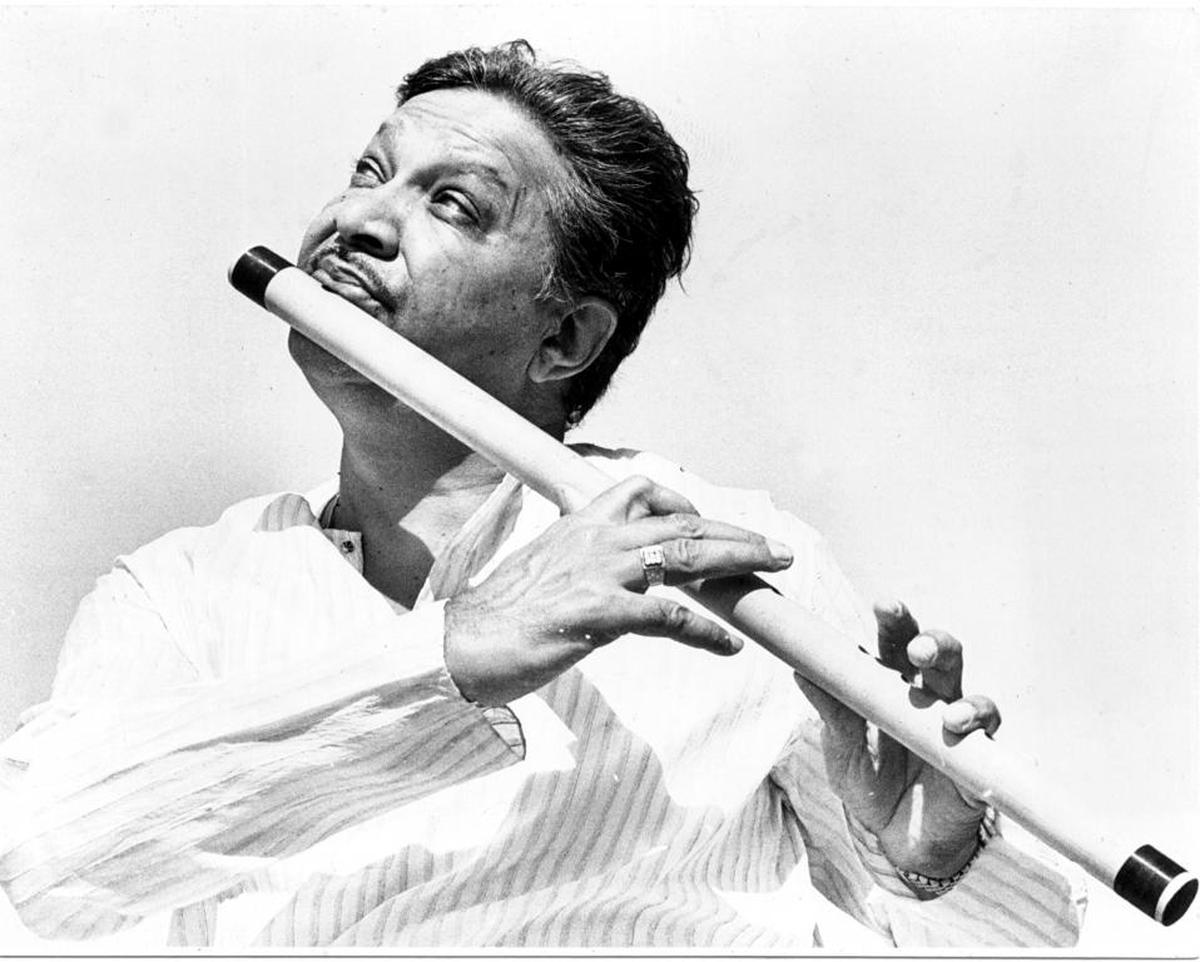

The maestro in his younger days | Photo Credit: Special Arrangement

Like the iconic French flautist Jean-Pierre Rampal, who is credited with taking the flute to great levels of popularity as a solo classical instrument, Pt. Chaurasia too has paved the way for future soloists. Much of it is also because of the instrument’s flexibility, yielding to diverse musical ideas and genres — classical, jazz, pop, blues and more. In Rampal’s hands, wrote American music and dance critic Allen Hughes, “an instrument that until recently was regarded as frail has become hearty, lively and brilliant.”

The Indian maestro has done the same with his extraordinary virtuosity. He combines discipline and freedom, two contrasting elements, in his approach. “Master the technique, and then set yourself free to find your distinct expression,” says Pt. Hariprasad Chaurasia briefly playing raag Desh. The dulcet sound of the bansuri echoes through Vrindaban. As you step out of the gurukul, a sculpture of Krishna on one of the outer walls seem to indicate the intricate bond between him and the flute’s renowned exponent.

See the original story with the video produced by Kanishka Balachandran by clicking on the link below:

END